"Photos: Before and After Carlisle" and "American Indian Boarding Schools Haunt Many"

Author: Brenna Farrell and Charla Bear

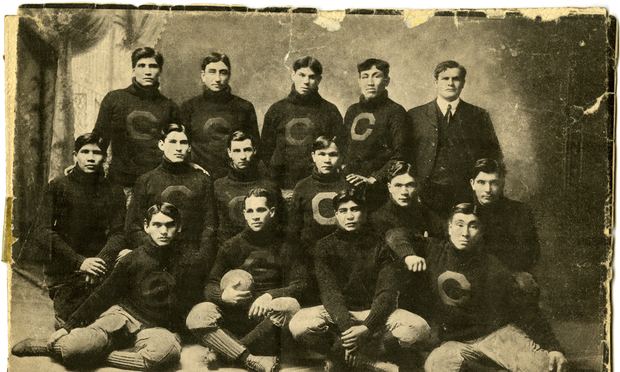

Carlisle Indian School's 1903 football team

The Cumberland County Historical Society in Carlisle, PA has boxes upon boxes of jaw-dropping photos and archives from the Carlisle Indian School -- including the "Before and After" student portraits we mention in our Carlisle story (go listen to our "American Football" episode!) .

Just to quickly set these images up... a little bit of backstory. The Carlisle Indian School was founded in 1879 by Colonel RH Pratt, a complicated figure with a troubling legacy. While he championed racial equality (something he set out to showcase at the school), his idea of equality was a peculiarly 19th Century one. He aimed to prove that American Indians were the equals of whites by making them as white as possible. His slogan at Carlisle was "kill the Indian, save the man." Students were forbidden from speaking their own languages. Their hair was cut, they were dressed in suits and ties and corseted dresses. They didn't go home for years at a time. And they were taught trades, like baking and blacksmithing, which were meant to give them a foothold in the white world after graduation. Yet many students had good experiences, and remembered Pratt as a good man... the "father of Indian education," as one student describes him in our story.

Since Pratt's mission was to show that American Indians still had a place in a world that was destroying their homes and cultures, he was eager to hold up examples of students succeeding on his terms. Pratt commissioned these "Before and After" photos to demonstrate the transformations happening at Carlisle.

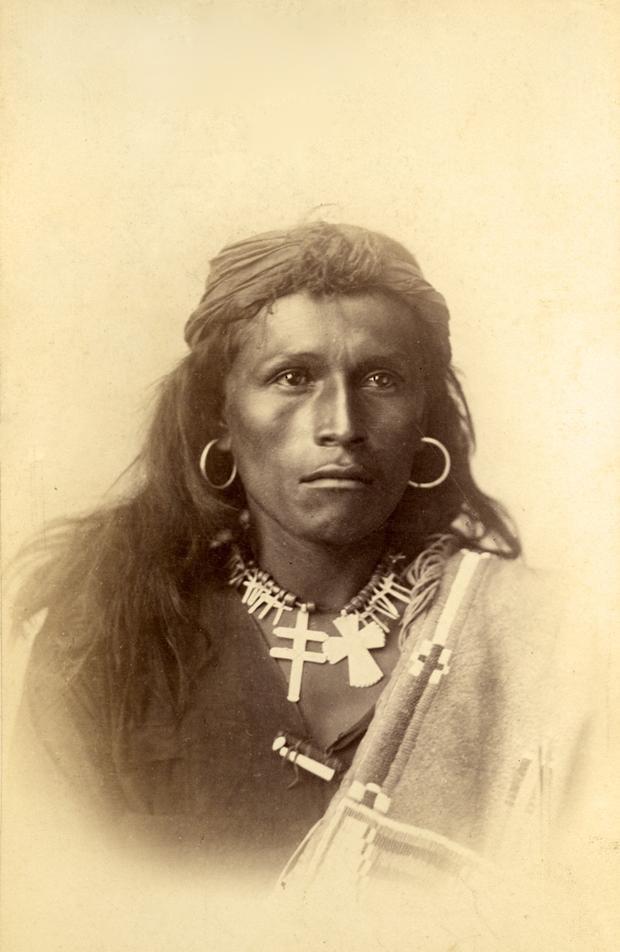

Let's start with the Tom Torlino -- his portraits are two of the most striking (and best-known) "Before and After" images. Taken by photographer John Choate in his Carlisle studio in 1882, this "before" photo was taken when Tom arrived at school, just a few years after it opened in 1879:

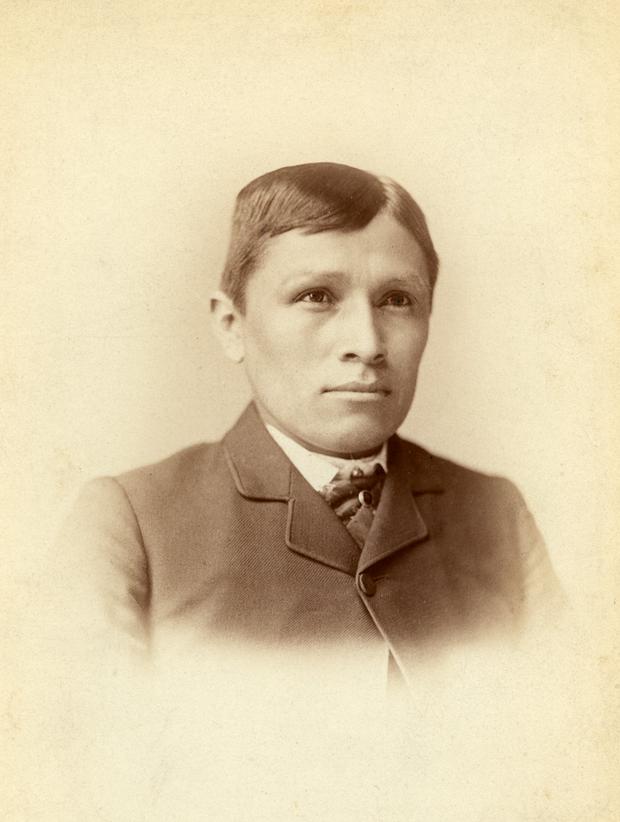

Here he is three years later, in 1885. Notice how much lighter Tom's skin appears in this photo. Barbara Landis and Richard Tritt from the Cumberland County Historical Society believe Choate manipulated the lighting to help make a point: with the proper education, Carlisle students could literally blend in with white society.

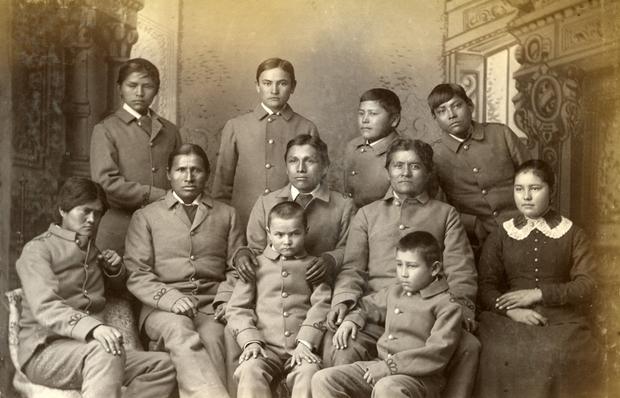

Here's another early shot, also from 1882, of twelve Navajo Students -- including Tom Torlino, sitting in the front row, bottom left. And that's RH Pratt looking on from the bandstand:

Then we have "Navajo Group who entered Carlisle October 21, 1882 after some time at the school." Once again, there's Tom Torlino -- sitting in the center row, third from left.

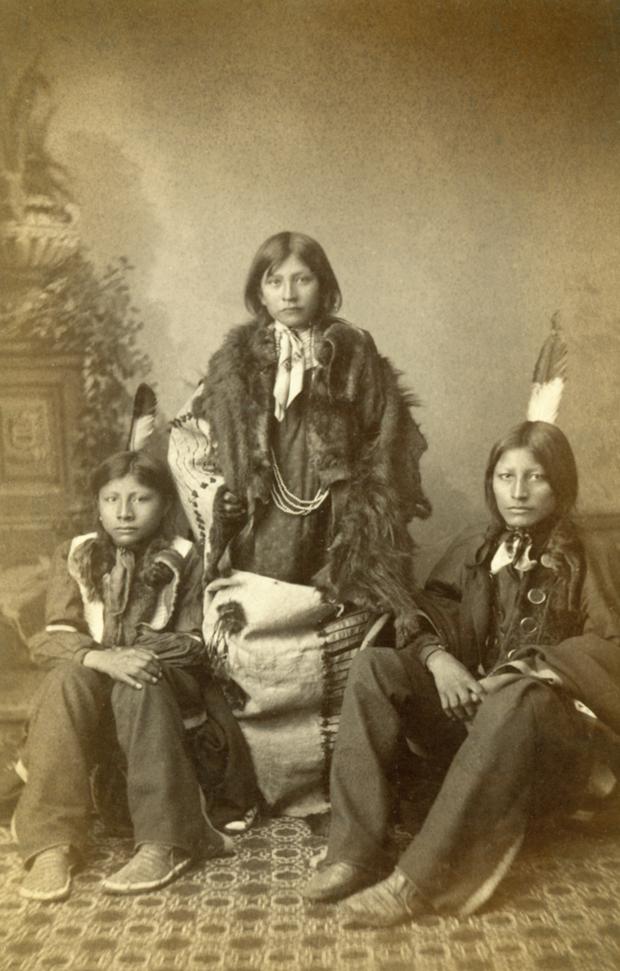

Here's another studio shot, this time of three Sioux boys. Richard Tritt, the CCHS photo archivist, explained that during these studio photo shoots, Choate had props and costumes on hand. It's not clear how much Choate controlled what the students wore, but it's worth bearing in mind... even though the caption on this photo describes "Three Sioux students as they arrived at the Carlisle Indian School in 1883:"

Here are the same three boys after three years at Carlisle, wearing cadet uniforms:

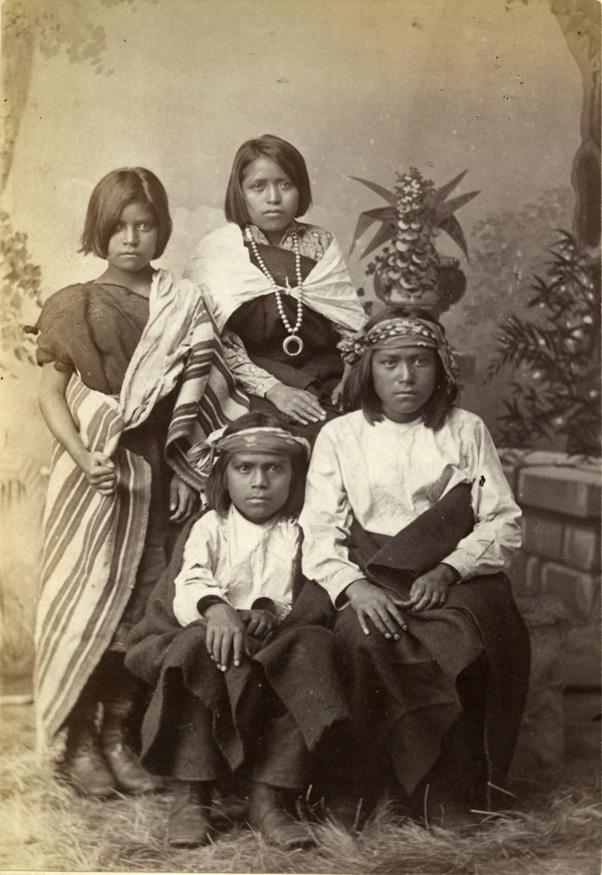

This photo of four Pueblo children is one of the few studio portraits that combines girls and boys. It was taken in 1880, just a year after the school opened:

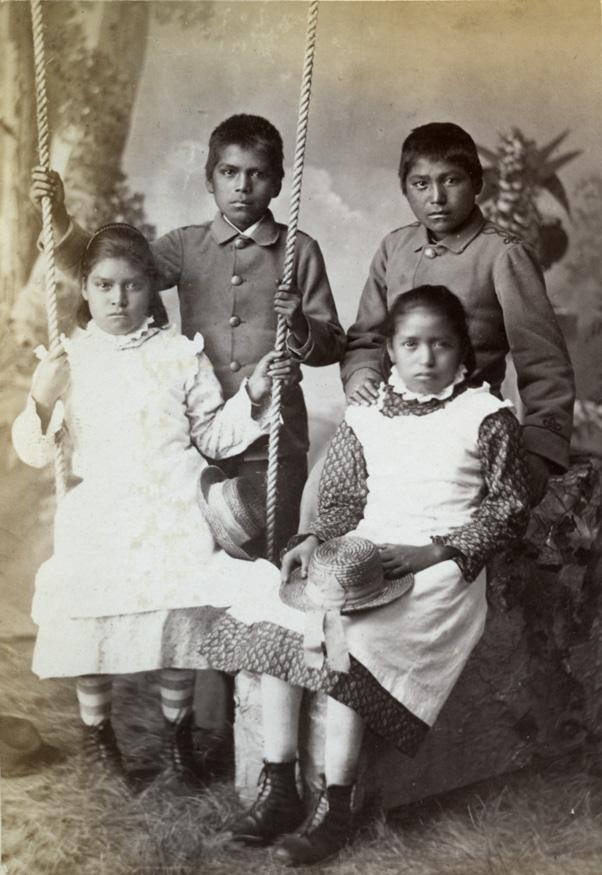

And now with hair cuts and uniforms:

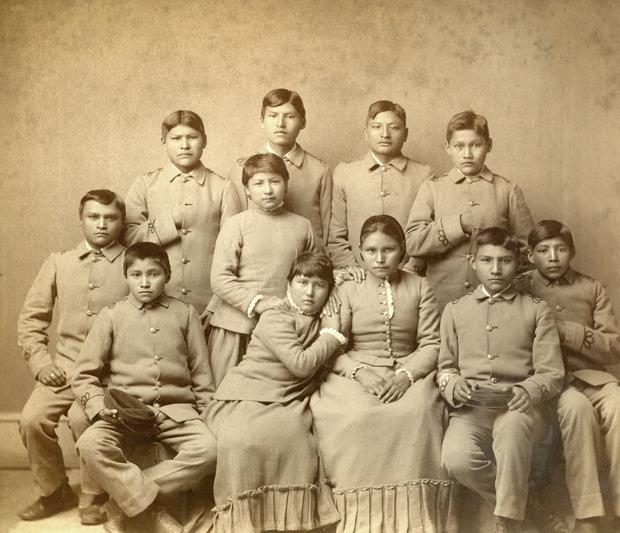

I find this photo so haunting -- it's a group of Chiricahua Apaches after arriving from a prison camp in Fort Marion, Florida (Pratt ran that prison before starting Carlisle). Barbara Landis explained that these were Geronimo's people, who were not allowed to return home. Conditions were terrible at Fort Marion, and as a result, the Apaches who came to Carlisle from Florida were some of the most unhealthy students at Carlisle, and many didn't survive. The school cemetery has a large number of Apache students buried there.

A few months later, from March, 1887: "Chiracahua Apaches four months after their arrival at Carlisle:"

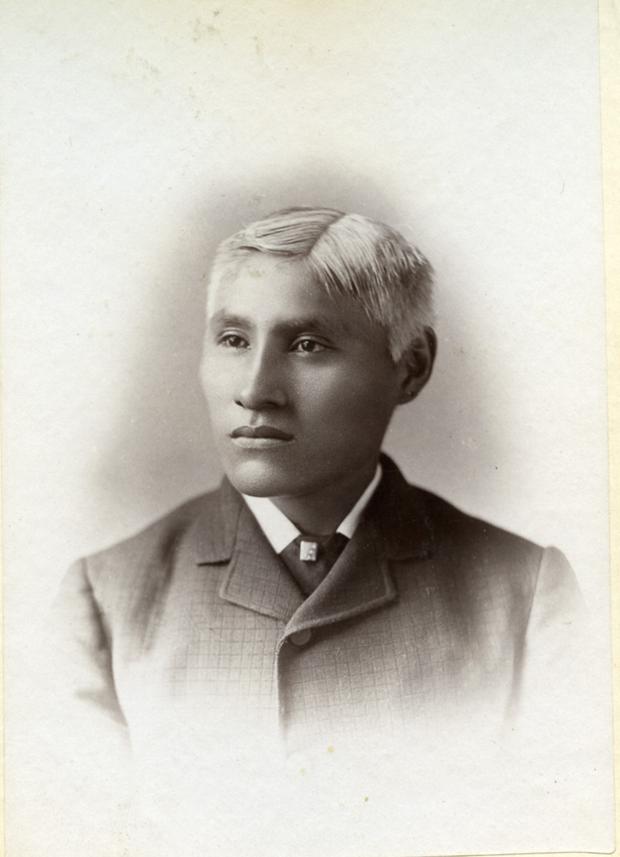

And finally, White Buffalo. White Buffalo was a student at Carlisle from 1881 to 1884. This photo was taken in 1881, when White Buffalo was 18 -- he had prematurely gray hair:

Here he is some time later, hair cropped and parted, with a jacket and tie:

-

BRENNA FARRELL

Brenna is a writer and radio maker who loves trees, stories, and people. Not necessarily in that order. She hails from the Adirondack Mountains, where she makes frequent getaways for ice-fishing, chopping wood, and chasing her toddler and husband through the mud and snow and tall grass.

American Indian Boarding Schools Haunt Many

RENEE MONTAGNE, host:

American Indians and the American government have lived with a harsh legacy for 130 years. The government took tens of thousands of Indian children far away from their reservations to schools where they were required to dress, pray, work and speak as mainstream Americans. Many Indians remember those boarding schools as places where they were abused and where their culture was desecrated.

After years of reforms, the government still operates a handful of off-reservation boarding schools, but funding is in decline, and now some Native Americans are fighting to keep the schools open. NPR's Charla Bear has the first of two reports.

CHARLA BEAR: The late performer and Indian activist Floyd Red Crow Westerman was haunted by his memories of boarding school. As a child, he left his reservation in South Dakota for the Wahpeton Indian Boarding School in North Dakota. Sixty years later, he still remembered watching his mother through the window of the government bus.

Mr. FLOYD RED CROW WESTERMAN (Performer and Indian Activist): My first impression, I thought my mother didn't want me. And it hit me hard like that. But when I got on the bus and I sat down and I looked, and she was just crying. It was hurting her, too. It was hurting me to see that. I'll never forget. All the mothers were crying.

BEAR: Westerman's music summed up the feelings of generations of former boarding school students.

(Soundbite of music)

Mr. WESTERMAN: (Singing) You put me in your a boarding school, made me learn your white man rule, be a fool...

BEAR: The federal government began sending American Indians to boarding schools in the late 1870s, when the United States was still at war with Indians. An Army officer, Richard Pratt, founded the first school that took children far from their reservations. He based it on an education program he had developed in an Indian prison. He described his philosophy in this speech, read by an actor.

Unidentified Man: A great general has said that the only good Indian is a dead one. In a sense, I agree with the sentiment, but only in this: that all the Indian there is in the race should be dead. Kill the Indian in him, and save the man.

In the 1940s, this philosophy was still common. Bill Wright, a Butwin Indian, left his reservation in California for the Stewart Indian School in Nevada when he was six. Wright says matrons bathed him in kerosene and shaved his head. Students at federal boarding schools were forbidden to express their culture - everything from wearing long hair to speaking even a single Indian word. Wright says he lost not only his language, but his native name.

Mr. BILL Wright: And I remember coming home, and, you know, my grandma asked me to talk Indian to me and I told Grandma, I don't understand you. She says, then who are you? I went, my name's Billy. She said, your name's not Billy. She says, your name is Tutum. That's who you are. That's your name. And I went, not what they told me.

Professor TSIANINA LOMAWAIMA (American Indian Studies, University of Arizona): The intent of the school was to completely transform people, I mean, inside out - language, religion, family structure, economics, the way you make a living, the way you express emotion, everything.

BEAR: Tsianina Lomawaima heads the American Indian Studies program at the University of Arizona. She says from the start, the government's objective to erase and replace Indian culture was part of a larger strategy to conquer Indians.

Ms. LOMAWAIMA: They very specifically targeted Native nations that were the most recently hostile. There was very a conscious effort to recruit the children of leaders, and this was also explicit, essentially to hold those children hostage. The idea was it going to be much easier to keep those communities pacified with their children held in a school somewhere far away.

BEAR: The government operated more than 100 boarding schools for American Indians, both on and off reservations. Children were sometimes taken forcibly, by armed police. Lomawaima says other families were willing let their children go.

Ms. LOMAWAIMA: For many communities, for a whole variety of reasons, federal school was the only option. Public schools in many places in the country were closed to Indians because of racism.

BEAR: At boarding schools, most students learned trades - carpentry for boys and housekeeping for girls.

Ms. LUCY TOLEDO (Navajo Indian, Attended Boarding School): It wasn't really about education. We didn't really learn English basic, English or math.

BEAR: Lucy Toledo, who's Navajo, went to Sherman Institute in California in the 1950s. She also remembers some unsettling free-time activities.

Ms. TOLEDO: Saturday night we have a movie. Every Saturday night. Do you know what the movie was about? Cowboys and Indians. Cowboys and Indians. Here we're getting all our people killed, and it's the kind of stuff they showed us.

(Soundbite of gunfire)

BEAR: And for decades, there were reports that students in the boarding schools were abused. Children were beaten, malnourished and forced to do heavy labor. In the 1960s, a congressional report found that many teachers still saw their role as civilizing Native American students, not educating them. The report said the schools still a, quote, "Major emphasis on discipline and punishment."

Bill Wright remembers an adviser hitting a student hard.

Mr. WRIGHT: Bust his head open and blood got all over him. I had to take him to the hospital, and they told me to tell them he run into the wall and I better not tell them what really happened.

Wright says he still has nightmares from the severe discipline. He worries that he and other former students have inadvertently recreated that harsh environment within their own families.

Mr. WRIGHT: It's mostly you do what I tell you. You jump when I tell you to jump, you don't talk back. So you grow up with discipline. But when you grow up and you have families, so what happens? If you was my daughter and if you left your dress over there, you know I'll knock you through that wall. Why? Because I'm taught discipline. And you go, like, ooh, man, better behave. But you have to look at - look what they've done to us.

BEAR: Not all Indians had negative experiences at boarding schools. Some have fond memories of meeting spouses and making lifelong friends. But the scathing government reports led to the closure of most of the boarding schools.

(Soundbite of children playing)

BEAR: One school that remains is Sherman Indian High School in Riverside, California, the same boarding school Lucy Toledo attended.

Hershel Martinez and a group of his friends gather casually in a school hallway and begin a drum circle.

(Soundbite of drumming)

BEAR: The school encourages native activities like this. That's one reason Martinez feels more comfortable here than at his former public school in Los Angeles.

Mr. HERSHEL MARTINEZ: And everyone was wondering what nationality, what race am I. And I'll tell them. They're like, oh wow, you're Indian? You're, like, the only guy I know that's native. But here, at Sherman, they know how I feel about being native, and they understand where we're all coming from.

(Soundbite of drumming)

BEAR: But a recent change in federal budgeting means the off-reservation boarding schools are receiving less money, and their future is in doubt.

Charla Bear, NPR News.

Copyright © 2008 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by Verb8tm, Inc., an NPR contractor, and produced using a proprietary transcription process developed with NPR. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

0 General Document comments

0 Sentence and Paragraph comments

0 Image and Video comments

I’m the Tech Liaison for the New York City Writing Project. I… (more)

I’m the Tech Liaison for the New York City Writing Project. I… (more)

New Conversation

Hide Thread Detail

General Document Comments 0