I prefer the window seat.

I like to idle away time on flights trying to guess where and what I’m flying over, without the benefit of the map. I’m hypnotized by the red-beige-brown carpet of California desert; mesmerized by the unbroken wilderness of northern Maine; awed by the peaks and valleys of the Cascades; calmed by the serenity of the Great Lakes.

And I draw a political conclusion: America is vast, largely empty and often lonely. Roughly 80 percent of Americans live in urban areas, covering just 3 percent of the overall landmass. We have a population density of 35 people per square kilometer — as opposed to 212 for Switzerland and 271 for the U.K.

We could use some more people. Make that a lot more.

That’s a point worth bearing in mind in the larger immigration debate unfolding in Congress. The Trump administration’s policy of forcibly separating migrant Latin American children from their parents was a moral outrage that, had it not been belatedly terminated on Wednesday, would have taken its place in the annals of American ignominy.

It was also a moral outrage that concealed a political folly. As of this writing, House Republicans are flailing in their efforts to pass a comprehensive immigration bill. That’s just as well since, as the Cato Institute’s David Bier points out, even the more moderate of the two G.O.P. bills would have cut overall legal immigration.

But that means we still need real immigration reform, and not simply as an act of decency toward so-called Dreamers brought to this country as children by their undocumented parents. America’s immigration crisis right now is that we don’t have enough immigrants.

Consider some facts.

First: The U.S. fertility rate has fallen to a record low. In May, The Times reported that women “had nearly 500,000 fewer babies than in 2007, despite the fact that there were an estimated 7 percent more women in their prime childbearing years.” That’s a harbinger of long-term, Japanese-style economic decline.

Second: Americans are getting older. In 2010 there were more than 40 million Americans over the age of 65. By 2050 the number will be closer to 90 million, or an estimated 22.1 percent of the population. That won’t be as catastrophic as Japan, where 40.1 percent of people will be over 65. But remember: We’ve only avoided Japan’s demographic fate so far by resisting its longstanding anti-immigration policies.

Third: The Federal Reserve has reported labor shortages in multiple industries throughout the country. That inhibits business growth. Nor are the shortages only a matter of missing “skills”: The New American Economy think tank estimates that the number of farm workers fell by 20 percent between 2002 and 2014, accounting for $3 billion a year in revenue losses.

Fourth: Much of rural or small-town America is emptying out. In hundreds of rural counties, more people are dying than are being born, according to the Department of Agriculture. The same Trumpian conservatives who claim to want to save the American heartland from the fabled Latin American Horde are guaranteeing conditions that over time will turn the heartland into a wasteland.

Fifth: The immigrant share (including the undocumented) of the U.S. population is not especially large: About 13.5 percent, high by recent history but below its late 19th century peak of 14.8 percent. In Israel, the share is 22.6 percent; in Australia, 27.7 percent, according to O.E.C.D. data, another indicator of the powerful correlation between high levels of immigration and sustained economic dynamism.

Finally, immigrants — legal or otherwise — make better citizens than native-born Americans. More entrepreneurial. More church-going. Less likely to have kids out of wedlock. Far less likely to commit crime. These are the kind of attributes Republicans claim to admire.

Or at least they used to, before they became the party of Trump — of his nativism, demagoguery, and penchant for capricious cruelty. It was nice to hear Republican legislators decry the family separation policy. But there’s no sugarcoating the fact that a plurality of Republicans, 46 percent, favored it, while only 32 percent were opposed, according to an Ipsos poll commissioned by the Daily Beast.

This isn’t a party that’s merely losing its policy bearings. It’s one that’s losing its moral sense. If anti-Semitism is the socialism of fools, then opposition to immigration is the conservatism of morons. It mistakes identity for virtue, entitlement for merit, geographic place for moral value. In a nation of immigrants, it’s un-American.

I’ll be accused of wanting open borders. Subtract terrorists, criminals, violent fanatics and political extremists from the mix, and I plead guilty to wanting more-open borders. Come on in. There’s more than enough room in this broad and fruitful land of the free.

Does America face a refugee or an immigration problem?

Jun. 29th, 2018

Separating children from their parents at the southwest border ignited a broad emotional outcry not often seen in the country’s long-running immigration debate. After weeks of defending the policy both as a deterrent and necessary to make the border legally meaningful, President Donald Trump and his administration reversed course.

The policy switch was itself a rarity for Trump, and it prompted the host of NBC’s Meet the Press Chuck Todd to ask the guests on his June 24 show, "Is this more of a refugee crisis than an immigration crisis?"

There is no definitive answer, but to frame the issue in terms of refugees instead of immigration redefines the problem.

"It becomes more of a humanitarian problem, than a jobs or economic one," said Sarah Pierce, an immigration analyst with the Migration Policy Institute.

We looked at what the data have to say.

For decades, the bulk of people crossing the southwest border without permission were Mexican. They worked on American farms, built American homes, processed American pigs, beef and chickens, and did other manual work.

The people showing up at the border today are more likely to come from El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras, a cluster known as the Northern Triangle. In 2017, non-Mexicans stopped at the southwest border outnumbered Mexicans by 50,000.

Not only are those nations poor, they are also particularly violent. The highest murder rates in the world are found in El Salvador and Honduras.

As the places people came from changed, so did the demographics of who was caught at the border.

Between 2013 and 2017, the number of families apprehended by Customs and Border Patrol agents rose five-fold, from 14,855 to 75,622.

Minors (anyone under 18) went from 7 percent of all people stopped at the border in 2011 to 27 percent in 2017 – nearly a four-fold increase. In the same period, the fraction of females, both children and adults, doubled from 13 percent of all apprehensions to 26 percent.

"The recent crisis brings very different immigrants from those who were undocumented and came in the 1990s," said economist Giovanni Peri at University of California, Davis. "They are younger, more vulnerable and more similar to refugees."

Peri, along with most researchers, emphasizes that migrants have a blend of motivations. In the case of the Northern Triangle countries, escaping poverty and fleeing violence go hand in hand.

Teasing out the relative weight of each is tricky.

Fortunately for us, one economist took a stab at it.

Around 2012, a surge of teenagers without their parents began arriving at the southwest border. By 2013, for the first time, the unaccompanied minors from El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras outnumbered those from Mexico. In 2014, they accounted for 75 percent of arrivals at the border.

U.S. authorities ended up collecting detailed information on 178,825 minors. Critically, that data included the towns and cities they had left behind.

Economist Michael Clemens at the Center for Global Development took that location data and ran it against the homicide data specific to those places. Violence, Clemens noted, isn’t spread evenly. It concentrates in hot spots.

He also folded in figures for local unemployment, income, poverty and school enrollment.

Clemens found that murders drive migration, but it wasn’t as simple as people fleeing the areas with the highest murder rates. What mattered most was a rise in homicides.

Clemens determined that on average, an increase of 1.08 homicides per year over four years in a community led to one additional minor from that community at the American border each year. To further complicate the picture, a jump in murders had a snowball effect, driving migration numbers up for several years going forward, even if the violence leveled off.

Clemens also found that poverty alone didn’t drive migration. Teenagers – and it was mainly 16-and-17-year-olds – tended not to come from the poorest places, but from places where there was enough money to pay smugglers to shepard minors through Mexico and across the U.S. border.

At the same time, there was a strong connection between sustained poverty and migration.

At the end of the day, Clemens gave about equal weight to violence and economic drivers.

The impact of "short-term increases in violence is roughly equal to the explanatory power of long-term economic characteristics like average income and poverty," Clemens wrote.

Put another way, the surge of minors at the U.S.-Mexico border is both an immigration and refugee issue.

A key caveat to Clemens’ work is that it looked only at unaccompanied minors, and it’s possible that the picture would change if adults and families were included. But based on studies of family migrants, Clemens said it likely would look the same.

"The decision for movement by unaccompanied children is one of safety and opportunity for children, and that is also heavily in the minds of family units," Clemens said. "The two kinds don’t self-report substantially different motives."

Clemens also noted that in the 2011-16 period, changes in U.S. policy had little impact on migration trends from the Northern Triangle.

For decades, a simple correlation tied illegal immigration from Mexico to the United States.

"When the U.S. unemployment rate went down, migration went up," said Jeffrey Passel, senior demographer at Pew Research. "If the unemployment rate went up, migration went down."

That held true through 2010. Then, the pattern stopped.

"After 2010, the unemployment rate dropped dramatically," Passel said. "If this model had held, Mexican migration would have gone up. Instead, Mexican migration went down."

Passel said the rise in numbers from other Central American countries, mainly the Northern Triangle group, is not a simple swap of one group for another. The demographic mix is entirely different.

"There’s something else going on that’s causing the Central American increase," Passel said. "The economy plays a role but it’s not solely determinative."

Passel and other researchers point to several reasons for the breakdown in the traditional pattern of illegal migration. Studies show a drop in the number of young men in Mexico, a group that was always the main source of border crossers. In some areas of Mexico, jobs are more available. And importantly, American border security has gone steadily up since about 2005.

"Just about everybody gets caught now," said Passel. "That seemed to work as a deterrent of Mexican migration, but those same factors don’t seem to be affecting Central American migration."

Peri, the UC Davis economist, suggested that the hardening of the border itself changed the mix of people caught trying to enter illegally.

"The very strict enforcement keeps away people who are motivated mainly by jobs, and selects only very desperate Central Americans, including many kids."

To the extent that dynamic is at work, then the primary solution to an immigration problem fueled a humanitarian one.

Legally, American laws and regulations count someone as a refugee by granting them asylum on the grounds that their personal safety is at risk if they stayed in their home country. As we’ve reported, the number of asylum requests has skyrocketed, but the fraction granted has held steady at about 20 percent.

"If they do not qualify for asylum either then they are not ‘refugees’ in the border sense of someone fleeing for their life and in need of resettlement," said the director of the Center for Immigration Studies Steven Camarota. The center promotes lower and more selective immigration.

"If someone has gone 1,500 miles through Mexico, and did not apply for asylum there, then it implies that they are not so much fleeing for their life, which is suppose to be the case for an asylee, but rather they are looking for a better life in the United States," Camarota said.

Passel at Pew Research noted that ties to family and friends play a large role when migrants pick a destination. Many people stopped at the border have an immediate or extended family member already in the United States. Migrants aim for places where community connections will help them once they arrive.

"Safety is one thing, but you have to live, too," Passel said.

0 General Document comments

0 Sentence and Paragraph comments

0 Image and Video comments

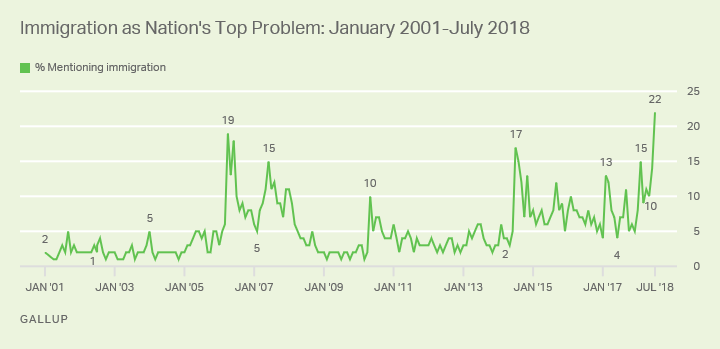

I haven’t read yet the reasons as to why those people who voted that immigration as the top problem in America, but could this separation of children be one of them? It caused an uproar across the nation that had many people wanting for reform.

New Conversation

Hide Full Comment

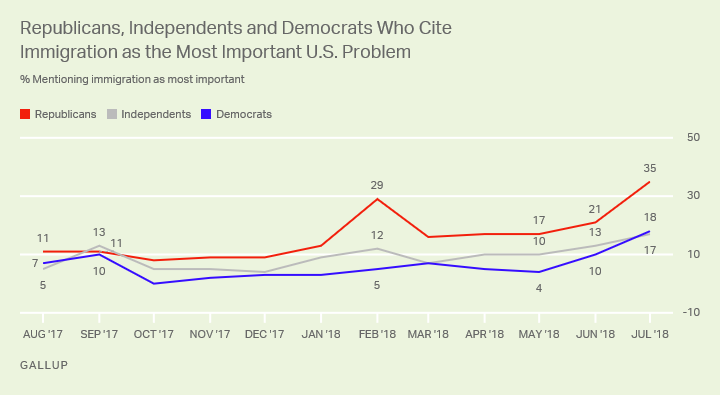

Republicans see immigration as a problem in affecting America’s economy and crime. Why do they assume immigrants are automatic criminals? Aren’t majority of immigrants in search for a better life? Democrats see immigration as a problem in how Trumps administration is handling it.

New Conversation

Hide Full Comment

I found it interesting seeing lack of respect for each other as one of the top problems in America. I can see it being one because today people can’t voice their opinions without someone attacking and not respecting their opinion.

New Conversation

Hide Full Comment

As he pointed out previously, America is a big country and there is room for a lot more people. I don’t oppose the idea of having more immigrants, but how would that affect the country? Why are there many Americans opposed to the idea of even having immigrants?

New Conversation

Hide Full Comment

If there is reported labor shortages, how are immigrants taking jobs from Americans? Yes, immigrants do affect the economy, but this line seems to support that immigrants affect the economy in a good way.

New Conversation

Hide Full Comment

As much as I would like to agree with this opinion, it still is just an opinion because it is supported with facts.

New Conversation

Hide Full Comment

I found this interesting because I still assumed that Mexican immigrants would be the majority crossing the border, but they are not anymore.

New Conversation

Hide Full Comment

I didn’t think of immigrants actually being refugees in that they are feeling very unsafe in their own country. It makes sense seeing the rising number of immigrants or rather refugees from countries that aren’t in the best conditions.

New Conversation

Hide Full Comment

This line has a point in saying immigrants from Central or South Americans that are seeking asylum aren’t actually seeking asylum, but a better life, because if their intentions were true, they would’ve seeked asylum in the countries they passed. But it still is not wrong wanting a better life.

New Conversation

Hide Full Comment

General Document Comments 0