"Bored Out of Their Mind," by Zachary Jason

Author: Zachary Jason

0 General Document comments

0 Sentence and Paragraph comments

0 Image and Video comments

Bored Out of Their Minds

For two weeks in third grade, I preached the gospel of the wild boar. My teacher, the sprightly Mrs. DeWilde, assigned my class an open-ended research project: Create a five-minute presentation about any exotic animal. I devoted my free time before bedtime to capturing the wonders of the Sus scrofa in a 20-minute sermon. I filled a poster as big as my 9-year-old self with photographs, facts, and charts, complete with a fold-out diagram of the snout. During my presentation, I shared my five-stanza rhyming poem about the swine’s life cycle, painted the species’ desert and taiga habitats in florid detail, and made uncanny snorting impressions. I attacked each new project that year — a sketch of the water cycle, a history of the Powhatan — with the same evangelism.

Flash forward to the fall of my senior year in high school, and my near-daily lunchtime routine: hunched over at a booth in Wendy’s, chocolate Frosty in my right hand, copying calculus worksheets from Jimmy and Spanish homework from Chris with my left while they copied my notes on Medea or Jane Eyre. Come class, I spent more time playing Snake on my graphing calculator than reviewing integrals, more time daydreaming than conjugating verbs.

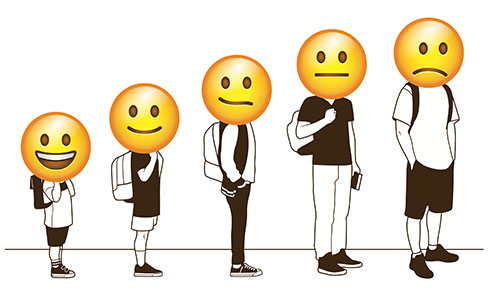

What happened in those nine years? Many things. But mainly, like the majority of my fellow Americans, I fell victim to the epidemic of classroom boredom.

A 2013 Gallup poll of 500,000 students in grades five through 12 found that nearly eight in 10 elementary students were “engaged” with school, that is, attentive, inquisitive, and generally optimistic. By high school, the number dropped to four in 10. A 2015 follow-up study found that less than a third of 11th-graders felt engaged. When Gallup asked teens in 2004 to select the top three words that describe how they feel in school from a list of 14 adjectives, “bored” was chosen most often, by half the students. “Tired” was second, at 42 percent. Only 2 percent said they were never bored. The evidence suggests that, on a daily basis, the vast majority of teenagers seriously contemplate banging their heads against their desks.

Some of boredom’s progression seems obvious, such as:

- An escalating emphasis on standardized tests. Fifth-grade teacher Jill Goldberg, Ed.M.’ 93, told me, “My freedom as a teacher continues to be curtailed with every passing year. I am not able to teach for the sake of teaching.” With lack of teacher freedom comes lack of student freedom, and disengagement and tuning out.

- The novelty of school itself fades with each grade. Here I am for another year in the same blue plastic chair, same graffitied fake wooden desk, surrounded by the same faces. Repetition begets boredom (e.g., I haven’t had a Frosty in a decade).

- Lack of motivation. Associate Professor Jal Mehta says, “There’s no big external motivating force in American education except for the small fraction of kids who want to go to the most selective colleges.”

- The transition from the tactile and creative to the cerebral and regimented. Mehta calls it the switch from “child-centered learning to subject-centered learning.” In third grade I cut with scissors, smeared glue sticks, and doodled with scented magic markers. By 12th grade I was plugging in formulas on a TI-83 and writing the answers on fill-in-the-blank worksheets. And research papers stimulate and beget rewards at a thousandth the speed of Snapchat and Instagram.

But who cares? Isn’t boredom just a natural side effect of daily life’s tedium? Until very recently, that’s how educators, academics, and neuroscientists alike have treated it. In fact, in the preface to Boredom: A Lively History, Peter Toohey presents the possibility that boredom might not even exist. What we call “boredom” might be just a “grab bag of a term” that covers “frustration, surfeit, depression, disgust, indifference, apathy.” Todd Rose, Ed.M.’ 01, Ed.D.’ 07, a lecturer at the Ed School and director of the Mind, Brain, and Education Program, says the American education system treats boredom as a “character flaw. We say, ‘If you’re bored in school, there’s something wrong with you.’”

But new research has begun to reveal boredom’s dismal effects in school and on the psyche. A 2014 study that followed 424 students at the University of Munich over the course of an academic year found a cycle in which boredom bore lower test results, which bore higher levels of boredom, which bore still lower test results. Boredom accounts for nearly a third of variation in student achievement. A 2010 German study found that boredom “instigates a desire to escape from the situation” that causes boredom. It’s not surprising, then, that half of high school dropouts cite boredom as their primary motivator for leaving. A 2003 Columbia University survey found that U.S. teenagers who said they were often bored were more than 50 percent more likely than not-bored teens to smoke, drink, and use illegal drugs. Proneness to boredom is also associated with anxiety, impulsiveness, hopelessness, loneliness, gambling, and depression. Educators and academics, Ed School faculty and alumni among them, have begun to engage with boredom, investigating its systemic causes and potential solutions. Mehta, who’s been studying engagement since 2010, says, “We have to stop seeing boredom as a frilly side effect. It is a central issue. Engagement is a precondition for learning,” he adds. “No learning happens until students agree to become engaged with the material.”

![]()

“Yo, Mr. P., I just wanted to let you know on Day One that I’m not a science person.”

“Mr. P., I’m not very good at science.”

“Science is not my favorite subject, Mr. P.”

Every year for 14 years, Victor Pereira Jr. (pictured, above), heard this from a handful of his students during the first week of his ninth- and 10th-grade science classes. After falling behind in specific subjects throughout elementary and middle school, students “were full of preconceived notions” of their capabilities, says Pereira, who taught at South Boston’s Excel High School before becoming a lecturer at the Ed School and master teacher in the Harvard Teacher Fellows Program. Engaging the students who are already discouraged was an uphill battle.

For comparison, Pereira remembers observing a second-grade science teacher’s lesson and leaving the class deflated. “Those kids were curious, they listened intently, and they were excited to take chances.” In second grade, he says, “you can use your common language and experiences from your everyday life to explain what’s happening and engage in the science lesson.” However, as students advance in science, learning its progressively technical terminology “requires almost learning another language.” Technicality can breed boredom and frustration, which breeds more boredom.

As Rose puts it, “The friction is cumulative.” For example, the best predictor for how students will fare in algebra is how they fared in prealgebra. A downward spiral emerges: “You’re not doing well, and you’re going to keep not doing well,” Rose says. “And then that becomes a part of how you see yourself as a learner.”

Rose has a master’s and doctorate from the Ed School, but he also had a 0.9 GPA in high school before he dropped out, primarily from boredom. He says he grew weary of the “poor design of the learning environment that creat-ed so many barriers to me being able to learn.” For one, because of his “pretty poor working memory,” he often forgot to bring home his homework or forgot to bring the homework he completed back to school. He says he was never taught skills like planning and organizing, and failed because the grading rubric neglected his style of learning. Eventually, “I couldn’t see why I should be there. They didn’t know why I should be there. We both agreed.”

Sam Semrow, Ed.M.’ 16, can relate. She attended a public high with a 10/10 rating on greatschools.com in a wealthy suburb of Chicago, but what she calls the “lack of individualized understanding of who we were as students” discouraged her. She read novels through math class, skipped days, contemplated dropping out, and barely graduated with a 1.8 GPA.

Rose has proposed a solution. In his book The End of Average, he illustrates that classrooms are falsely designed to cater to the “average learner.” Fourth-graders take tests and read texts written at a “fourth-grade reading level” that assume an “average” fourth-grader’s knowledge of rock formations and the Civil War and the “average” fourth-grader’s cognitive development. In reality, Rose says, “that average fourth-grader doesn’t exist.” Each student is much more “jagged” in his or her skill-set — advanced in memory, underdeveloped in organization, say, or vice versa. By designing for the average of everyone, the classroom is ideal to no one. And in this design, boredom runs rampant, and there’s no room for a cure.

“If you see human potential as a bell curve and there are only some kids who are going to be great and most kids are mediocre, then engagement really wouldn’t matter,” Rose says. “But if you really believe that all kids are capable, then you would build environments that really worked hard to sustain engagement and nurture potential.”

Rose suggests adding much more choice to the classroom. Allow exams to be written or taken orally. Assign students more hands-on projects, in which they become in control of their own learning. New research bolsters his theory. Since 2011 Mehta and current doctoral student Sarah Fine, Ed.M.’ 13, have been studying “deeper learning” (learning that is both challenging and engaging; see sidebar) at more than 30 American high schools, and they have found that schools with the most project-based curricula tend to foster the fewest bored students.

Of course, no teacher can assign and grade 30 individual projects and create 30 individual lesson plans every day. Rose suggests schools more often exploit digital, scalable technologies that can deliver readings and assignments tailored to specific types of learners. With boredom, Rose says, “the focus is on the curriculum first. I think we can talk to teachers about it second. Let’s do something for them instead of asking more of them.

![]()

Still, teachers can staunch boredom. Mehta and Fine (read sidebar) discovered that even in underperforming schools where boredom was near universal, “there were individual teachers who were creating classrooms where students were really engaged and motivated.” These teachers trusted students to sometime control the class. They tried to learn from their students as much as they taught. They weren’t afraid to go off script.

In some ways it’s no surprise Spanish and calculus were my worst subjects senior year: They had the most monotonous curricula and the dullest teachers. In Spanish we spent weeks watching the “educational” and horrendously acted soap opera La Catrina and more weeks slogging through call-and-response lessons recorded 20 years earlier, on cassette. I had by then ruled out a career in math, and my teacher did little to explain the pertinence of limits and derivatives in my life beyond that I may fail another test. My English and U.S. history teachers, however, inspired me to thrive. Mr. Howell had us imagine how Huckleberry Finn’s Jim and Pap would interact if they were guests on Da Ali G Show and helped us identify fallacies by having us debate the war in Iraq. And Mr. Rice culminated each chapter of American history with a class-wide debate in which we each assumed the role of a different figure from that period, bonus points for showing up in costume.

Of course, there’s value in teaching students to suck it up and work. As Mehta (pictured, above) notes, learning any discipline or gaining any skill requires a certain amount of “necessary boredom. ... If you want to be a great violinist, you’ve got to practice your scales. You want to play basket-ball? You’ve got to shoot your free throws.” An overemphasis on engagement, Emory professor Mark Bauerlein writes in “The Paradox of Classroom Boredom” in Education Week, may inadvertently “stunt students in preparation” for college, where pushing through tedious work — like memorizing equations for organic chemistry — is required to advance. “In telling [students], ‘You think the material is pointless and musty, but we’ll find ways to stimulate you,’ high school educators fail to teach them the essential skill of exerting oneself even when bored.”

“The problem,” Mehta says, “is that we haven’t created trajectories where students see the meaning and purpose that would make the necessary boredom endurable.” The problem is relevance.

Every teacher and academic I talked to kept coming back to relevance. Semrow says she grew bored because for most subjects, “I didn’t see what it meant for my life.” Few teachers contextualized their lessons. “Especially for 17- and 18-year-olds, we’re dealing with a lot of issues about what’s next for us.” The curriculum rarely addressed how trigonometry and human anatomy fit into her future. But Semrow says she graduated by the grace of the few teachers who did stress relevance.

Pereira says that the examples of how biology fit into his students’ lives — for example, explaining the water cycle through the Flint, Michigan, water crisis — often “weren’t good enough. They’re not in teenage language.” To counter that, he often let students “give better examples that translate to the larger group.” And when the class seemed particularly bored, he made room for in-class adjustments to reignite the lesson. For example, when he started a photosynthesis lesson one day, students sighed, “We already know this.” But one student brought up a news article about scientists who were experimenting with growing plants in space. Pereira then decided the students would design their own photosynthesis experiment testing various wavelengths and light intensities, and then present their data in a form of a letter of recommendation to NASA.

Rose adds that high schools rarely take advantage of an adolescent’s cognitive development. Teenagers “take on identities; they’re more socially oriented. This is the first time when abstract ideas can be motivating. They become more politically engaged and think about things like justice. Yet we’re still keeping them in the kind of education system... that wants nothing from them in terms of their own ideas. School has already decided what matters and [what it] expects from you. It’s like an airplane: Sit down, strap in, don’t talk, look forward. Why would it be meaningful?”

The beauty of relevance, Rose says, “is that it’s free. If you’re an educator or curriculum developer, and you saw your responsibility to ensure every kid knew why they were doing what they were doing, you can do that tomorrow.”

![]()

Of course, impassioned teachers who communicate the relevance of their lessons often aren’t enough. Jill Goldberg, Ed.M.’ 93, who teaches fifth grade at a public school in Newtonville, New York, has been shaping her lessons to be more interesting and relevant for the past 24 years. Still, her students fiddle with pencils, scribble notes to friends, and “practically have drool coming out of their mouths.” She tells them, “I wish there was a full-wall mirror behind me ... so you could see what your faces and body language convey to me.”

Goldberg lays some blame on parents. When she asks her students why they’re in school, “they tell me it is because their parents work and so this is where they need to be during the day. Some say it’s like their ‘job’ to go to school. ... No child ever [says] that learning and being educated is important. No one ever says that they love to learn new things no matter what the subject. No parents or students seem to believe that pure learning for the sake of learning is the goal.

“Why do my students’ parents work?” Goldberg adds. “They most likely tell their children that they work in order to make money in order to live the life they want to live. But do they love their work? Why have they chosen the field in which they work? Are these adults who are inspired to make the world a better place?”

Rose (pictured, above), however, cautions against casting too much blame on parents. “Even though it feels right, it will excuse [society] from the responsibility of how we rethink our own environments in the classroom.”

For example, poor scheduling also cultivates boredom. Seven a.m. start times for high school often mean rising at dawn to catch the bus, which means much less sleep than the National Sleep Foundation’s recommended eight to 10 hours a night, which means severely diminished alertness. In most high schools, regardless of the subject, the day’s first classes have the worst average grade. Schools that have bumped start times an hour later have seen the number of Ds and Fs cut in half.

Mehta adds that “having students take six or seven classes of 45 or 50 minutes at a time basically gives them enough time to just start to do something before the period ends.” Often, much of that time is spent reviewing homework and menial tasks, exacerbating boredom. Semrow notes that “being in school longer would have given teachers more free time to reach out to me” to get to know her strengths and weaknesses as a learner.

Educators and scientists have yet to agree on a definition of boredom, let alone unearth its exact causes and cures in the classroom. The most exhaustive book on the subject to date, Boredom in the Classroom: Addressing Student Motivation, Self-Regulation, and Engagement in Learning, is 72 pages long. As Dean James Ryan recently wrote in Education Week, “Boredom ought to be considered much more seriously when thinking about ways to improve student outcomes. ... I would think it is in all of our interests at least to confront this stubborn fact of school rather than simply to accept boredom as inextricably linked to learning.”

“But the biggest shift we need,” Rose believes, is much more elemental. “We need to get away from thinking that the opposite of ‘bored’ is ‘entertained.’ It’s ‘engaged.’” It’s not about pumping cartoons and virtual reality games into the classroom, it’s about finding ways to make curriculum more resonant, personalized, and meaningful for every student. “Engagement is very meaningful at a neurological level, at a learning level, and a behavioral level. When kids are engaged, life is so much easier.”

Zachary Jason is a Boston-based writer who writes for Boston Magazine, the Boston Globe Magazine, and The Guardian.

Read about Rose's End of Average research in our Fall 2015 issue.

Read "Why the Periphery Is Often More Powerful Than the Core" by Jal Mehta and Sarah Fine, Ed.M.' 13

Read Dean Ryan's blog post on boredom in Education Week.

Illustration by Todd Detwiler; Photos by Tim Llewellyn

General Document Comments 0

0 archived comments