Individualism vs. Collectivism: Our Future, Our Choice

0 General Document comments

0 Sentence and Paragraph comments

0 Image and Video comments

theobjectivestandard.com

Individualism vs. Collectivism: Our Future, Our Choice

The fundamental political conflict in America today is, as it has been for a century, individualism vs. collectivism. Does the individual’s life belong to him—or does it belong to the group, the community, society, or the state? With government expanding ever more rapidly—seizing and spending more and more of our money on “entitlement” programs and corporate bailouts, and intruding on our businesses and lives in increasingly onerous ways—the need for clarity on this issue has never been greater. Let us begin by defining the terms at hand.

Individualism is the idea that the individual’s life belongs to him and that he has an inalienable right to live it as he sees fit, to act on his own judgment, to keep and use the product of his effort, and to pursue the values of his choosing. It’s the idea that the individual is sovereign, an end in himself, and the fundamental unit of moral concern. This is the ideal that the American Founders set forth and sought to establish when they drafted the Declaration and the Constitution and created a country in which the individual’s rights to life, liberty, property, and the pursuit of happiness were to be recognized and protected.

Collectivism is the idea that the individual’s life belongs not to him but to the group or society of which he is merely a part, that he has no rights, and that he must sacrifice his values and goals for the group’s “greater good.” According to collectivism, the group or society is the basic unit of moral concern, and the individual is of value only insofar as he serves the group. As one advocate of this idea puts it: “Man has no rights except those which society permits him to enjoy. From the day of his birth until the day of his death society allows him to enjoy certain so-called rights and deprives him of others; not . . . because society desires especially to favor or oppress the individual, but because its own preservation, welfare, and happiness are the prime considerations.” 1

Interesting line! We most definitely see people like this concerned with their individual self rather than belonging to a larger organization.

Individualism or collectivism—which of these ideas is correct? Which has the facts on its side?

Individualism does, and we can see this at every level of philosophic inquiry: from metaphysics, the branch of philosophy concerned with the fundamental nature of reality; to epistemology, the branch concerned with the nature and means of knowledge; to ethics, the branch concerned with the nature of value and proper human action; to politics, the branch concerned with a proper social system.

We’ll take them in turn.

Metaphysics, Individualism, and Collectivism

When we look out at the world and see people, we see separate, distinct individuals. The individuals may be in groups (say, on a soccer team or in a business venture), but the indivisible beings we see are individual people. Each has his own body, his own mind, his own life. Groups, insofar as they exist, are nothing more than individuals who have come together to interact for some purpose. This is an observable fact about the way the world is. It is not a matter of personal opinion or social convention, and it is not rationally debatable. It is a perceptual-level, metaphysically given fact. Things are what they are; human beings are individuals.

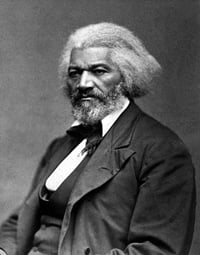

A beautiful statement of the metaphysical fact of individualism was provided by former slave Frederick Douglass in a letter he wrote to his ex-“master” Thomas Auld after escaping bondage in Maryland and fleeing to New York. “I have often thought I should like to explain to you the grounds upon which I have justified myself in running away from you,” wrote Douglass. “I am almost ashamed to do so now, for by this time you may have discovered them yourself. I will, however, glance at them.” You see, said Douglass,

I am myself; you are yourself; we are two distinct persons, equal persons. What you are, I am. You are a man, and so am I. God created both, and made us separate beings. I am not by nature bound to you, or you to me. Nature does not make your existence depend upon me, or mine to depend upon yours. I cannot walk upon your legs, or you upon mine. I cannot breathe for you, or you for me; I must breathe for myself, and you for yourself. We are distinct persons, and are each equally provided with faculties necessary to our individual existence. In leaving you, I took nothing but what belonged to me, and in no way lessened your means for obtaining an honest living. Your faculties remained yours, and mine became useful to their rightful owner.2

Although one could quibble with the notion that “God” creates people, Douglass’s basic metaphysical point is clearly sound. Human beings are by nature distinct, separate beings, each with his own body and his own faculties necessary to his own existence. Human beings are not in any way metaphysically attached or dependent on one another; each must use his own mind and direct his own body; no one else can do either for him. People are individuals. “I am myself; you are yourself; we are two distinct persons.”

The individual is metaphysically real; he exists in and of himself; he is the basic unit of human life. Groups or collectives of people—whether families, partnerships, communities, or societies—are not metaphysically real; they do not exist in and of themselves; they are not fundamental units of human life. Rather, they are some number of individuals. This is perceptually self-evident. We can seethat it is true.

Who says otherwise? Collectivists do. John Dewey, a father of pragmatism and modern “liberalism,” explains the collectivist notion as follows:

Society in its unified and structural character is the fact of the case; the non-social individual is an abstraction arrived at by imagining what man would be if all his human qualities were taken away. Society, as a real whole, is the normal order, and the mass as an aggregate of isolated units is the fiction.3

According to collectivism, the group or society is metaphysically real—and the individual is a mere abstraction, a fiction.4

This, of course, is ridiculous, but there you have it. On the metaphysics of collectivism, you and I (and Mr. Douglass) are fictional, and we become real only insofar as we somehow interrelate with society. As to exactly how we must interrelate with the collective in order to become part of the “real whole,” we’ll hear about that shortly.

Let us turn now to the branch of philosophy concerned with the nature of knowledge.

Epistemology, Individualism, and Collectivism

What is knowledge? Where does it come from? How do we know what’s true? Knowledge is a mental grasp of a fact (or facts) of reality reached by perceptual observation or a process of reason based thereon.5 Who looks at reality, hears reality, touches reality, reasons about reality—and thereby gains knowledge of reality? The individual does. The individual possesses eyes, ears, hands, and the like. The individual possesses a mind and the capacity to use it. He perceives reality (e.g., dogs, cats, and birds, and death); he integrates his perceptions into concepts (e.g., “dog,” “animal,” and “mortal”); he integrates his concepts into generalizations (e.g., “dogs can bite” and “animals are mortal”); he forms principles (e.g., “animals, including man, must take certain actions in order to remain alive,” and “man requires freedom in order to live and prosper”). And so on. Knowledge is a product of the perceptual observations and mental integrations of individuals.

Of course, individuals can learn from other people, they can teach others what they have learned—and they can do so in groups. But in any such transmission of knowledge, the individual’s senses must do the perceiving, and his mind must do the integrating. Groups don’t have sensory apparatuses or minds; only individuals do. This, too, is simply unassailable.

But that doesn’t stop collectivists from denying it.

The relevant epistemological principle, writes Helen Longino (chair of the philosophy department at Stanford University) is that “knowledge is produced by cognitive processes that are fundamentally social.” Granted, she says, “without individuals there would be no knowledge” because “it is through their sensory system that the natural world enters cognition. . . . The activities of knowledge construction, however, are the activities of individuals in interaction”; thus knowledge “is constructed not by individuals, but by an interactive dialogic community.” 6

You can’t make this stuff up. But an “interactive dialogic community” can.

Although it is true (and should be unremarkable) that individuals in a society can exchange ideas and learn from one another, the fact remains that the individual, not the community, has a mind; the individual, not the group, does the thinking; the individual, not society, produces knowledge; and the individual, not society, shares that knowledge with others who, in turn, must use their individual minds if they are to grasp it. Any individual who chooses to observe the facts of reality can see that this is so. The fact that certain “philosophers” (or “dialogic communities”) deny it has no bearing on the truth of the matter.

Correct epistemology—the truth about the nature and source of knowledge—is on the side of individualism, not collectivism.

Next up are the respective views of morality that follow from these foundations.

Ethics, Individualism, and Collectivism

What is the nature of good and bad, right and wrong? How, in principle, should people act? Such are the questions of ethics or morality (I use these terms interchangeably). Why do these questions arise? Why do we need to answer them? Such questions arise and need to be answered only because individuals exist and need principled guidance about how to live and prosper.

We are not born knowing how to survive and achieve happiness, nor do we gain such knowledge automatically, nor, if we do gain it, do we act on such knowledge automatically. (As evidence, observe the countless miserable people in the world.) If we want to live and prosper, we need principled guidance toward that end. Ethics is the branch of philosophy dedicated to providing such guidance.

For instance, a proper morality says to the individual: Go by reason (as against faith or feelings)—look at reality, identify the nature of things, make causal connections, use logic—because reason is your only means of knowledge, and thus your only means of choosing and achieving life-serving goals and values. Morality also says: Be honest—don’t pretend that facts are other than they are, don’t make up alternate realities in your mind and treat them as real—because reality is absolute and cannot be faked out of existence, and because you need to understand the real world in order to succeed in it. Morality further provides guidance for dealing specifically with people. For instance, it says: Be just—judge people rationally, according to the available and relevant facts, and treat them accordingly, as they deserve to be treated—because this policy is crucial to establishing and maintaining good relationships and to avoiding, ending, or managing bad ones. And morality says: Be independent—think and judge for yourself, don’t turn to others for what to believe or accept—because truth is not correspondence to the views of other people but correspondence to the facts of reality. And so on.

By means of such guidance (and the foregoing is just a brief indication), morality enables the individual to live and thrive. And that is precisely the purpose of moral guidance: to help the individual choose and achieve life-serving goals and values, such as an education, a career, recreational activities, friendships, and romance. The purpose of morality is, as the great individualist Ayn Rand put it, to teach you to enjoy yourself and live.

Just as the individual, not the group, is metaphysically real—and just as the individual, not the collective, has a mind and thinks—so too the individual, not the community or society, is the fundamental unit of moral concern. The individual is morally an end in himself, not a means to the ends of others. Each individual should pursue his life-serving values and respect the rights of others to do the same. This is the morality that flows from the metaphysics and epistemology of individualism.

What morality flows from the metaphysics and epistemology of collectivism? Just what you would expect: a morality in which the collective is the basic unit of moral concern.

On the collectivist view of morality, explains “progressive” intellectual A. Maurice Low, “that which more than anything marks the distinction between civilized and uncivilized society is that in the former the individual is nothing and society is everything; in the latter society is nothing and the individual is everything.” Mr. Low assisted with the definition of collectivism at the outset of this article; here he elaborates with emphasis on the alleged “civility” of collectivism:

In a civilized society man has no rights except those which society permits him to enjoy. From the day of his birth until the day of his death society allows him to enjoy certain so-called rights and deprives him of others; not . . . because society desires especially to favor or oppress the individual, but because its own preservation, welfare, and happiness are the prime considerations. And so that society may not perish, so that it may reach a still higher plane, so that men and women may become better citizens, society permits them certain privileges and restricts them in the use of others. Sometimes in the exercise of this power the individual is put to a great deal of inconvenience, even, at times, he suffers what appears to be injustice. This is to be regretted, but it is inevitable. The aim of civilized society is to do the greatest good to the greatest number, and because the largest number may derive benefit from the largest good the individual must subordinate his own desires or inclinations for the benefit of all.7

Because Mr. Low wrote that in 1913—before Stalin, Mao, Hitler, Mussolini, Pol Pot, and company tortured and murdered hundreds of millions of people explicitly in the name of “the greatest good for the greatest number”—he may be granted some small degree of leniency. Today’s collectivists, however, have no such excuse.

As Ayn Rand wrote in 1946, and as every adult who chooses to think can now appreciate,

“The greatest good for the greatest number” is one of the most vicious slogans ever foisted on humanity. This slogan has no concrete, specific meaning. There is no way to interpret it benevolently, but a great many ways in which it can be used to justify the most vicious actions.

Paragraph 43 0

Dec 17Christopher Clyne Christopher Clyne : This is coming right after the attrocities of the holocaust, justified by the utilitarian principle that Ayn writes against.

Dec 17Christopher Clyne Christopher Clyne : This is coming right after the attrocities of the holocaust, justified by the utilitarian principle that Ayn writes against.What is the definition of “the good” in this slogan? None, except: whatever is good for the greatest number. Who, in any particular issue, decides what is good for the greatest number? Why, the greatest number.

If you consider this moral, you would have to approve of the following examples, which are exact applications of this slogan in practice: fifty-one percent of humanity enslaving the other forty-nine; nine hungry cannibals eating the tenth one; a lynching mob murdering a man whom they consider dangerous to the community.

There were seventy million Germans in Germany and six hundred thousand Jews. The greatest number (the Germans) supported the Nazi government which told them that their greatest good would be served by exterminating the smaller number (the Jews) and grabbing their property. This was the horror achieved in practice by a vicious slogan accepted in theory.

But, you might say, the majority in all these examples did not achieve any real good for itself either? No. It didn’t. Because “the good” is not determined by counting numbers and is not achieved by the sacrifice of anyone to anyone.8

The collectivist notion of morality is patently evil and demonstrably false. The good of the community logically cannot take priority over that of the individual because the only reason moral concepts such as “good” and “should” are necessary in the first place is that individuals exist and need principled guidance in order to sustain and further their lives. Any attempt to turn the purpose of morality against the individual—the fundamental unit of human reality and thus of moral concern—is not merely a moral crime; it is an attempt to annihilate morality as such.

To be sure, societies—consisting as they do of individuals—need moral principles, too, but only for the purpose of enabling individuals to act in ways necessary to sustain and further their own lives. Thus, the one moral principle that a society must embrace if it is to be a civilized society is the principle of individual rights: the recognition of the fact that each individual is morally an end in himself and has a moral prerogative to act on his judgment for his own sake, free from coercion by others. On this principle, each individual has a right to think and act as he sees fit; he has a right to produce and trade the products of his efforts voluntarily, by mutual consent to mutual benefit; he has a right to disregard complaints that he is not serving some so-called “greater good”—and no one, including groups and governments, has a moral right to force him to act against his judgment. Ever.

This brings us to the realm of politics.

Politics, Individualism, and Collectivism

The politics of individualism is essentially what the American Founders had in mind when they created the United States but were unable to implement perfectly: a land of liberty, a society in which the government does only one thing and does it well—protects the rights of all individuals equally by banning the use of physical force from social relationships and by using force only in retaliation and only against those who initiate its use. In such a society, government uses force as necessary against thieves, extortionists, murderers, rapists, terrorists, and the like—but it leaves peaceful, rights-respecting citizens completely free to live their lives and pursue their happiness in accordance with their own judgment.

Toward that end, a proper, rights-respecting government consists of legislatures, courts, police, a military, and any other branches and departments necessary to the protection of individual rights. This is the essence of the politics of individualism, which follows logically from the metaphysics, epistemology, and ethics of individualism.

What politics follows from those of collectivism?

“America works best when its citizens put aside individual self-interest to do great things together—when we elevate the common good,” writes David Callahan of the collectivist think tank Demos.9 Michael Tomasky, editor of Democracy, elaborates, explaining that modern “liberalism was built around the idea—the philosophical principle—that citizens should be called upon to look beyond their own self-interest and work for a greater common interest.”

This, historically, is the moral basis of liberal governance—not justice, not equality, not rights, not diversity, not government, and not even prosperity or opportunity. Liberal governance is about demanding of citizens that they balance self-interest with common interest. . . . This is the only justification leaders can make to citizens for liberal governance, really: That all are being asked to contribute to a project larger than themselves. . . . citizens sacrificing for and participating in the creation of a common good.10

This is the ideology of today’s left in general, including, of course, President Barack Obama. As Obama puts it, we must heed the “call to sacrifice” and uphold our “core ethical and moral obligation” to “look out for one another” and to “be unified in service to a greater good.” 11 “Individual actions, individual dreams, are not sufficient. We must unite in collective action, build collective institutions and organizations.” 12

But modern “liberals” and new “progressives” are not alone in their advocacy of the politics of collectivism. Joining them are impostors of the right, such as Rick Santorum, who pose as advocates of liberty but, in their perverted advocacy, annihilate the very concept of liberty.

“Properly defined,” writes Santorum, “liberty is freedom coupled with responsibility to something bigger or higher than the self. It is the pursuit of our dreams with an eye toward the common good. Liberty is the dual activity of lifting our eyes to the heavens while at the same time extending our hands and hearts to our neighbor.” 13 It is not “the freedom to be as selfish as I want to be,” or “the freedom to be left alone,” but “the freedom to attend to one’s duties—duties to God, to family, and to neighbors.” 14

Such is the state of politics in America today, and this is the choice we face: Americans can either continue to ignore the fact that collectivism is utterly corrupt from the ground up, and thus continue down the road to statism and tyranny—or we can look at reality, use our minds, acknowledge the absurdities of collectivism and the atrocities that follow from it, and shout the truth from the rooftops and across the Internet.

What would happen if we did the latter? As Ayn Rand said, “You would be surprised how quickly the ideologists of collectivism retreat when they encounter a confident, intellectual adversary. Their case rests on appealing to human confusion, ignorance, dishonesty, cowardice, despair. Take the side they dare not approach; appeal to human intelligence.” 15

General Document Comments 0

0 archived comments