Ketamine: Exploring continuation-phase treatment for depression

0 General Document comments

0 Sentence and Paragraph comments

0 Image and Video comments

Ketamine is known to have short-term effectiveness for the treatment of nonpsychotic, treatment-resistant unipolar and bipolar major depression. Within hours of receiving treatment, patients who benefit from intravenous (IV) ketamine have experienced onset of clinical antidepressive response lasting on average three to 14 days. Little is known, however, about the antidepressive effects and safety of repeated IV ketamine infusions beyond the acute phase of treatment.

Researchers at Mayo Clinic's campus in Rochester, Minnesota, have demonstrated that continuation-phase administration of ketamine at weekly intervals to patients with treatment-resistant depression who remitted during acute-phase ketamine treatment can extend the duration of depressive-symptom remission. In a small feasibility study published in the Journal of Affective Disorders in 2016, the antidepressive effect of ketamine persisted for several weeks after the end of continuation-phase treatment.

"We know that we can infuse ketamine acutely and have a certain rate of success. But even when we give multiple infusions over, say, a two-week period, a lot of patients will relapse in about 18 days," says William V. Bobo, M.D., M.P.H., a psychiatrist specializing in the evaluation and treatment of depression at Mayo Clinic's campus in Minnesota. "We are very interested in investigating whether we can extend the duration of effect of ketamine into a continuation phase of treatment, for patients who have failed multiple medications and neuromodulation."

In the clinical study, 12 participants with treatment-resistant major depression and suicidal ideation were given thrice-weekly IV infusions of ketamine. Five of the 12 remitted and received an additional weekly ketamine infusion for four weeks, followed by four weeks of follow-up during which no ketamine was administered. All five experienced further depressive symptom improvement during continuation-phase treatment.

"These are patients who have not responded well to multiple trials of conventional medications or electroconvulsive therapy," Dr. Bobo says. "Ketamine could be an alternative treatment for these patients someday, if we can define optimization and even a maintenance phase for individual patients, so it is safe and effective for them."

Adverse effects were generally mild and transient during the acute and continuation phases of treatment. However, one participant developed behavioral outbursts and suicide threats during follow-up while hospitalized, and another died by suicide several weeks after the end of follow-up. According to Dr. Bobo, ketamine was not effective for either of these patients. "These outcomes highlight that we still need to learn more about the best ways to improve ketamine treatment and extend its therapeutic benefits for very severely depressed patients," he says.

A foundation of laboratory science

-

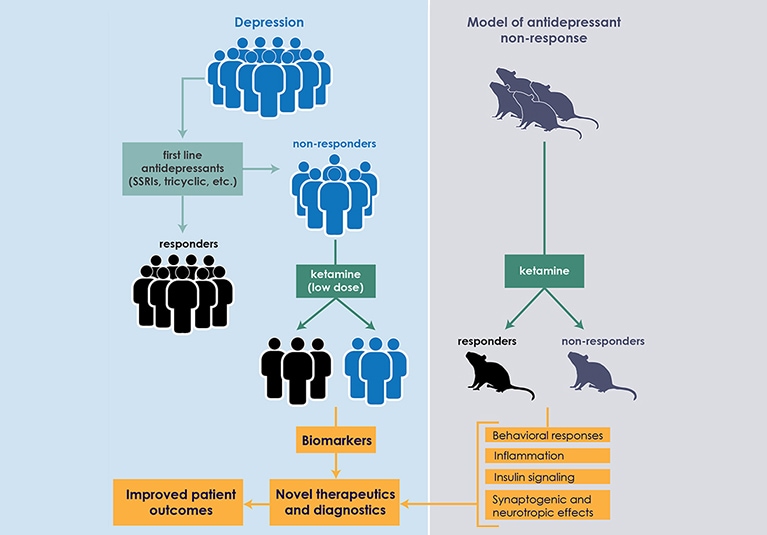

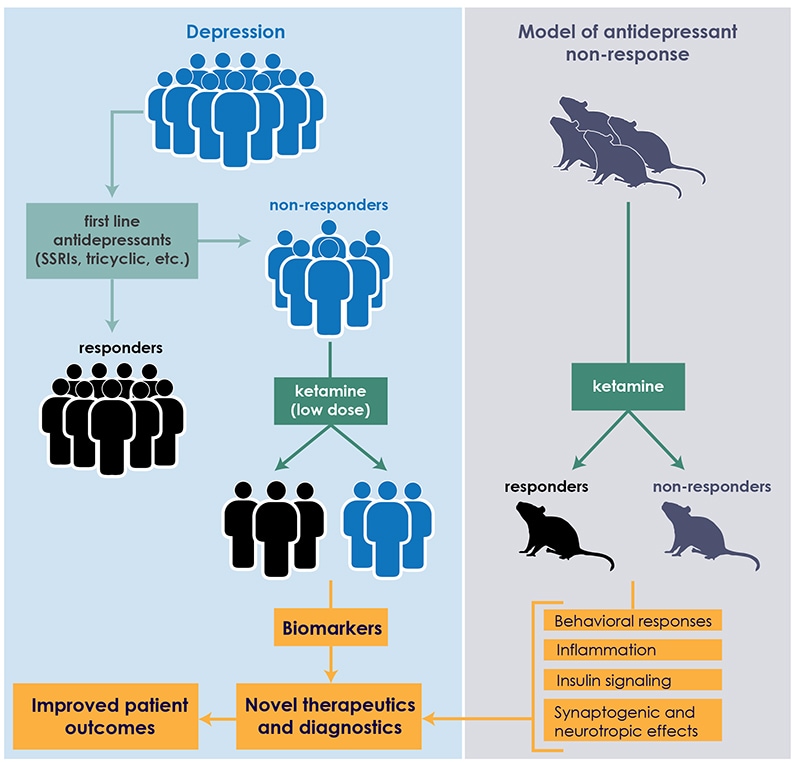

Interface between clinical practice and preclinical research

At Mayo Clinic, the clinical study of ketamine is undergirded by laboratory quests for biomarkers that can predict patient response to antidepressants. "We're focused on linking brain mechanisms with peripheral biomarkers in preclinical rodent studies, which we then validate in our clinical studies," says Susannah J. Tye, Ph.D., director of the translational neuroscience laboratory based within the Mayo Clinic Depression Center. "In peripheral blood measures, we've identified some of the mechanisms that seem to be interfering with depression-treatment response."

Ketamine is an N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor antagonist and anti-inflammatory agent. In a study published in Behavioural Brain Research in 2015, Mayo Clinic scientists found an association between plasma levels of two proinflammatory proteins — tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) and C-reactive protein (CRP) — and response to ketamine in laboratory models. The antidepressant-resistant rodent models were pre-treated for 14 days with either adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) or saline. The animals were then randomly assigned to groups receiving ketamine or control vehicle saline. After behavioral testing, the models' plasma was analyzed for interleukin 6 (IL-6), TNF-alpha and CRP.

This ACTH-pre-treatment has been shown to impair the animals' abilities to respond to antidepressants most commonly prescribed early in the course of depressive illness. Mayo Clinic investigators are exploring the biological mechanisms that may contribute to this poor response, and developing means of circumnavigating these factors.

In the ketamine study, not all of the ACTH-pre-treated animals responded effectively to ketamine. Similar to the clinical response rates, approximately half exhibited a therapeutic response. Plasma testing showed no significant effects on IL-6; however, levels of TNF-alpha and CRP differentiated these ketamine responders and nonresponders.

To validate those results in clinical studies, Dr. Tye and colleagues are analyzing blood samples from Dr. Bobo's patients. "We're running those assays, and they look promising," she says. "If these mechanisms are truly differentiating responders and nonresponders, we would like to target those mechanisms with adjunctive treatments that are currently available, with the hope that the adjunctive treatments will improve treatment response rates in patients, as well as extend the duration of that response."

"Our goal is always to develop clinical-basic science partnerships that enable research projects with the potential to impact our clinical practice," Dr. Bobo adds. "That collaboration is inculcated in our culture at Mayo Clinic, and it's one of the most rewarding aspects of our work."

General Document Comments 0

0 archived comments