Drought survival: What Australia's changes can teach California

Author: Kevin Fagan

Fagan, Kevin. “Drought Survival: What Australia's Changes Can Teach California.” San Francisco Chronicle, 30 Sept. 2015, www.sfchronicle.com/news/article/Drought-survival-What-Australia-s-changes-can-6528480.php.

MELBOURNE, Australia — Four years into what degenerated into this country’s worst drought ever, John Harvey would have been recognizable to anyone now living through California’s driest days.

First, the retired photo-equipment salesman let his grass go dead. Next, his decorative plants turned brown.

But then came the fifth and sixth years of the sun baking the landscape like a heat lamp, with water bills rising each year — and Harvey finally had enough. He did something he would have never done if not forced to by wretched circumstance: With the government’s help, he installed a home water-recycling system.

That same awakening blossomed again and again in Australia, as what came to be known as the Big Dry dragged on for 13 punishing years. By the time the rains finally returned in 2010, the country had utterly changed in ways that California — with a similar landscape and economy, struggling to cope after four years of its own epic drought — could learn from.

Cities sprouted backyard water tanks. Modern-day rooftop rain-barrel systems spread through the suburbs, fueled by government incentives. Farmers who once had the right to use all the water they wanted, just because it had always been that way, were forced to change.

And John Harvey’s yard not only survived, it thrived.

Today, his water bill is zero, and his plants are always green. That’s because his water comes from rain that flows into his gray-water system, and he reuses every drop — over and over.

“I never even notice anymore if it’s a dry year or not,” Harvey, 75, said as he cleaned the filters on his network of pipelines at his Craftsman brick home in suburban Melbourne. “All I need is one good rainstorm to fill my tanks, and I’m good to go for months. I don’t spend a single dollar on water, and let me tell you, mate, I don’t miss that one bit.”

Faced with disaster — with the prospect of its lifeblood running out — Australia learned to manage its water like the rare treasure it is.

“What we finally realized was we can’t just rely on building more dams and hoping there’s more rain,” said Kelly O’Shanassy, architect of some of the most fundamental changes in Australia’s water usage. “It’s just a brick wall if there’s no water behind it, and during our drought we were one or two years away from actually running out of water. So we had to be creative.

“The climate is going to be very dry going forward in Australia, drier than before,” O’Shanassy said. “But we are better prepared for it than ever.”

As in California, scientific studies indicate that about half of all the years going forward in Australia are likely to be stricken by drought. To ignore that is to summon disaster, O’Shanassy said.

“The future,” she said, “looks nothing like the past.”

Rocky Varapodio, major stone fruit farmer and owner of Oakmoor Orchards in Ardmona, Victoria, Australia.

Shot on August 28, 2015.Eriver Hijano/Special to the Chronicle

Rocky Varapodio, major stone fruit farmer and owner of Oakmoor Orchards in Ardmona, Victoria, Australia.

Shot on August 28, 2015.Eriver Hijano/Special to the Chronicle

A worker inspects fruit at Rocky Varapodio's Oakmoor Orchards in Ardmona, Victoria, Australia.

Shot on August 28, 2015.Eriver Hijano/Special to the Chronicle

A worker inspects fruit at Rocky Varapodio's Oakmoor Orchards in Ardmona, Victoria, Australia.

Shot on August 28, 2015.Eriver Hijano/Special to the Chronicle

Russell Pell, owner of the dairy Pell Family Farms in Wyuna, Victoria, Australia, September 1, 2015.Eriver Hijano/Special to the Chronicle

Russell Pell, owner of the dairy Pell Family Farms in Wyuna, Victoria, Australia, September 1, 2015.Eriver Hijano/Special to the Chronicle

Cutting usage in half

At the end of the Big Dry, Australia’s cities and farms had cut their water use in half, double the 25 percent target that California has set this year. Farmers and environmentalists had been forced to share rivers and reservoirs equally, after sweeping away a rat’s-maze system of unassailable water rights similar to the Golden State’s.

Today, two-thirds of Australia’s houses use gray-water systems that recycle water from dishwashers, showers and clothes-washing for their toilets and gardens and, in many cases, for their drinking water. More than half of all homes have barrels to catch rain from the roof for those gray-water systems — and one good rainstorm can supply enough for a house all summer.

In California, just 13 percent of homes use gray water, and rain barrels have never caught on.

Water rates in Australia are more expensive for heavy users, and in times of drought, inspectors patrol neighborhoods, issuing on-the-spot fines of up to $500 for exceeding government-set limits.

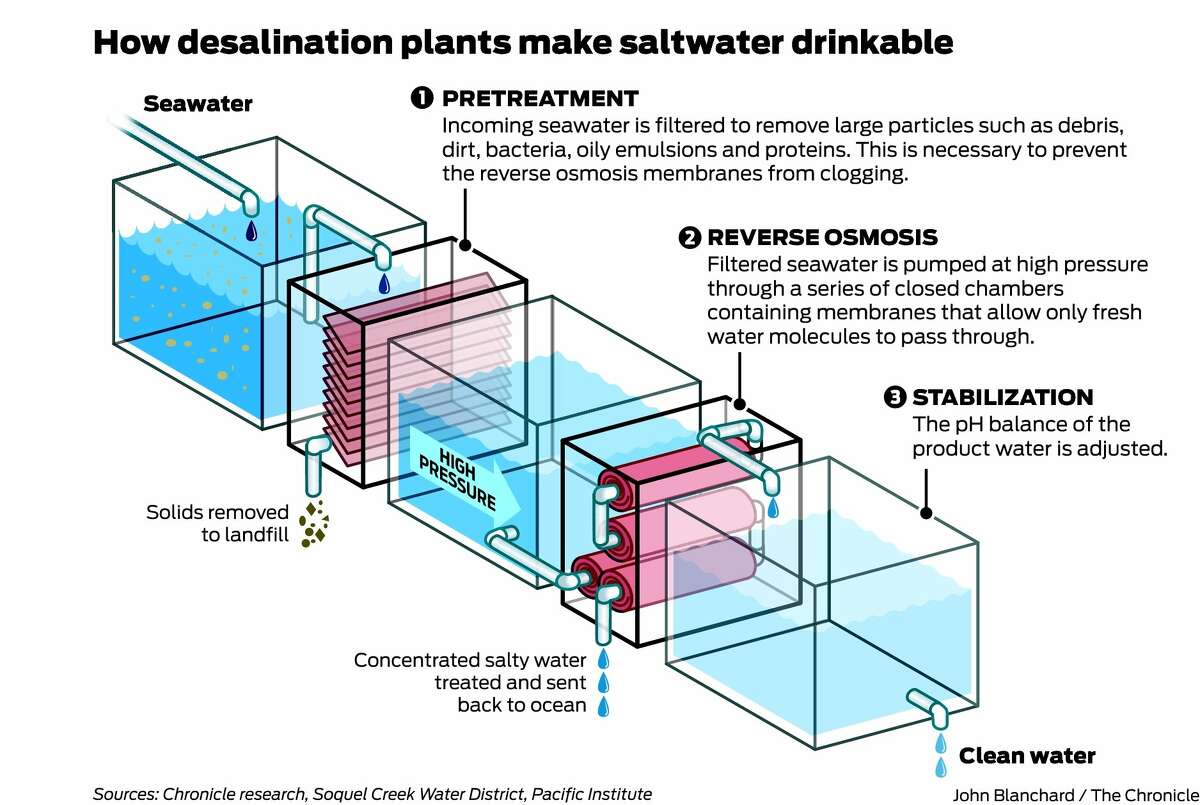

And just to make sure wrenching changes won’t be needed in the future, Australia’s government subsidized the private construction of six giant desalination plants that together can supply 30 percent of the country’s metropolitan water needs when — not if — the cousin of the Big Dry comes to call.

The changes didn’t come cheap. Encouraging recycling and water-saving plumbing, plus helping farmers improve conservation, cost Australian taxpayers more than $13 billion. Water rates rose, and for customers in cities that built desalination plants, they nearly doubled.

“It wasn’t all rose-colored glasses making this happen,” said Rebecca Nelson, a professor of water law at the University of Melbourne who doubles as a fellow at Stanford University’s Woods Institute for the Environment. “But, basically, everyone here was accepting of the need to share resources in the public interest. It really seemed like we all had no choice.

“And it helped that the federal government backed it all up with sacks of money.”

In many cases, the investment was not a hard sell. The country’s will was there.

“One thing that really struck me about Australia was that everyone thought in the drought, ‘We’re all in this together,’” said Matthew Heberger, a researcher at the Pacific Institute in Oakland who has studied how Australia handled the Big Dry. “But here in California, there’s a sense of blaming — farmers blaming cities, cities blaming farmers, environmentalists and non-environmentalists.

“One of the lessons we can learn from Australia is that we need to stop thinking of drought as an exceptional thing, but rather as a normal and recurring part of our climate,” Heberger said. “And then move forward on that, together.”

Radical change

The cities are where the changes are most obvious.

In the arid Outback, rain barrels and other makeshift gray-water systems have been common for hundreds of years. But Australia’s cities are much like California’s — especially Melbourne, a modern enclave of lovely architecture and a laid-back San Francisco feel — and they didn’t really sweat the whole recycling thing until the Big Dry.

Melbourne and its suburbs at the southern tip of the nation boast a population of 4.3 million, identical to the inner Bay Area. Both areas get about 24 inches of rain in a normal year. But while the average Bay Area person’s water use is 84 gallons a day, in Melbourne it’s a stingy 40 gallons.

The secret is purple: the international color of piping for gray-water systems. As Australia’s reservoir levels plunged to 25 percent of capacity, everything from tract homes to high-rise office buildings began sporting purple pipes.

Out on the eastern edge of Melbourne, in a pretty little neighborhood of meat-pie shops and trim homes, John Harvey was one of the most ambitious gray-water enthusiasts. Many followed his lead, which is why their vegetable gardens — a fixture of many Aussie homes — and small trees never died out.

“At first the neighbors wondered what I was about, but then they caught on,” Harvey said. “It’s not hard to see the worth of purple pipes once you hear that your neighbor doesn’t have water bills anymore.”

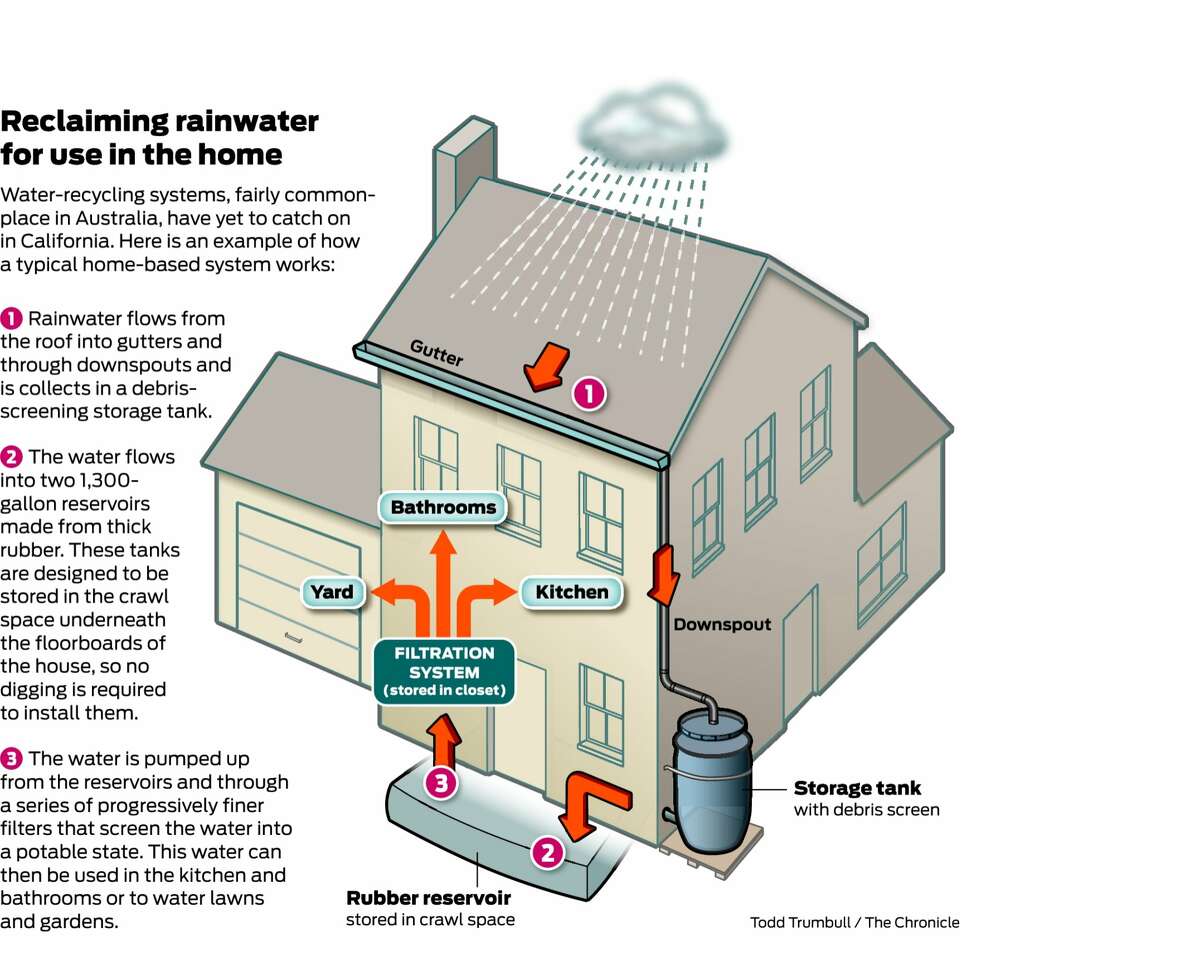

His gray-water system is pretty standard stuff for Australian homes. A couple of downspouts route water from the roof into a debris-screening tank. From there, it flows into two thick-rubber, 1,300-gallon tanks under his house. The tanks were easy to install — they were shoved below the floorboards into the crawl space, no digging required.

A small electric pump pulls the rubber-tank water up through a series of three progressively finer filters in a closet, then off to the bathrooms, kitchen and yard. The filters screen the water into potable state, with no chemicals needed.

John Harvey, 75, a retired Melbourne homeowner, installed an impressive array of recycling and gray-water systems that have cut his water bill to zero.Eriver Hijano/Special to the Chronicle

John Harvey, 75, a retired Melbourne homeowner, installed an impressive array of recycling and gray-water systems that have cut his water bill to zero.Eriver Hijano/Special to the Chronicle

Harvey makes sure to use only biodegradable soaps — which, driven by gray-water usage, are the main ones sold in Australia anyway.

Government rebates can total more than $1,000 to anyone installing gray-water and rain-barrel systems. Although Harvey spent $15,000 on his setup, a simple, non-potable system for gardens and toilets can cost as little as $2,000 — a bargain, considering that the water bill for the average house that doesn’t recycle is about $2,000 a year.

“Just because it’s been raining this winter doesn’t mean there won’t be a drought next year, or the year after that,” Harvey said. “I reckon farmers in the Outback and bush have been drinking rainwater since colonization days. It’s only right that we’re all starting to do it now.”

As recycling spread, the techniques got more sophisticated. The very way a garden is grown in the backyard became an art, and one of that art’s pioneers was Karen Sutherland, who owns the Edible Eden Design gardening firm in a leafy suburb on the north end of Melbourne.

Sutherland uses her home’s spread of grapes, avocados and other crops as a showcase for how to make every drop count — from the gray-water system with moisture-sensitive drip irrigation to the practice of growing shady fruit trees over crops to protect them from drying heat. Her business exploded during the Big Dry.

“I think the drought was a gift for city people, in a way,” Sutherland said. “It forced everyone to be more creative.”

Saving at the office

Also riding the purple-pipe bandwagon are Melbourne’s downtown office buildings. About half of them have installed at least minimal gray-water systems since the beginning of the drought.

Leading the way was a downtown high-rise known as the 60L Building, headquarters of an environmental advocacy organization run by O’Shanassy, the Australian Conservation Foundation. It opened in 2002 with the help of government subsidies as “the greenest building in Australia,” but its signature colors are more properly described as gray and black — the soapy and the sewage water, respectively, that is recycled in such quantities that the building’s consumption is just 10 percent of average for a structure its size.

While the neighborhoods and downtowns were transforming, the government was making fundamental changes of its own. Melbourne has spent more than $100 million on storm-water systems, which include “rain gardens” to filter runoff through the ground into a series of underground tanks, some of them the size of Olympic swimming pools. Most of the water used in the city’s public parks comes from this supply.

Kelly O'Shanassy, executive director of the Australian Conservation Foundation, in the 60L Green Building, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia on August 27, 2015.Eriver Hijano/Special to the Chronicle

Kelly O'Shanassy, executive director of the Australian Conservation Foundation, in the 60L Green Building, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia on August 27, 2015.Eriver Hijano/Special to the Chronicle

“The fact is, we can’t rely solely on rainwater anymore for all our needs,” said O’Shanassy, who was hired by the government during the drought to redraw water policy for Melbourne and the surrounding countryside. “You need efficiency, redistributed supplies and alternatives like desalination. You have to try to make use of every drop, everywhere.”

California has started taking baby steps toward desalination, with a plant set to open this fall in Carlsbad, near San Diego, to turn 50 million gallons a day of the Pacific Ocean into potable water. It will be the first major metropolitan area in the state to tap the ocean for drinking water, and more than a dozen other plants are in planning stages.

However, such plants have faced opposition from critics who say they are too expensive, kill fish as they suck in briny water, and spew greenhouse gases from the energy they require to run.

Not everyone in Australia was a fan, either. Melbourne’s plant 84 miles east of the city cost $5.7 billion, and by the time it was done in 2012, the rains were falling again and it wasn’t needed — so, like most of the nation’s desalination plants, it has sat idle.

This draws grumbles from people like Peter Wilson, head of Waterwise Systems, the country’s biggest gray-water systems installer, who called it a “white elephant that we would never have had to build if we’d had better water education and conservation measures earlier.”

O’Shanassy said those complaints will dry up faster than an Outback raindrop when the next big drought hits. Melbourne’s plant can supply a third of the city’s water needs, and it’s run largely by wind and hydro power.

“Government studies show us we can’t count on rainfall and that in fact, by midcentury, we’ll have up to 50 percent less water available to us,” she said. “So it’s simple. We will need the extra supply.”

Water rights transformed

The recycling efforts in the cities are a drop in the bucket compared with the changes that have swept over farm country.

As in California, Australia’s agricultural operations suck up about 80 percent of the water supply. And for Melbourne, just as for the Bay Area, the main farming region of the nation is just a couple of hours away.

Australia’s version of the Central Valley is the Murray-Darling Basin, named after the rivers that cut through the farmlands north of Melbourne. Both regions are the size of small states in themselves and grow similar crops ranging from almonds to grapes, and both historically have wrestled with cities and environmental advocates for water.

Driving from Melbourne into farmland that Aussies call the Food Basket has an oddly familiar feel for a Californian. Skyscrapers give way to suburbs that quickly surrender to rolling, tree-studded hills known here as the bush.

Just 120 miles north of Melbourne, the Food Basket opens up like an endless flatland — field after field of crops laced with canals, forests and tiny farm towns.

It looks like the hillocks and flats of Fresno County. And it is here, as the ag center of the country, that the most radical changes of the Big Dry took place.

When the drought hit, Australia had a water rights system much like California’s — those with senior claims tied into their land could tap as much as they liked, and everyone else had to make due with less.

For all the conservation edicts that California has imposed during its drought, this water-rights system is viewed in the Golden State as all but unassailable — no serious efforts have been made to change it.

Australia approached things differently. It turned the system on its head.

The government set stiff limits on water supplies for farmers and cities alike during the drought, spreading out allotments from rivers and reservoirs equally according to need. Then it canceled the historic practice of tying water rights to land plots, and set up a robust water-trading system, encouraging anyone to sell their rights to anyone, anywhere.

That created a market that still trades briskly at $1 billion a year, as farmers bandy water back and forth depending on which crop needs it the most at what time of year — oranges or pumpkins here, livestock or almonds there.

The most significant player in this game is the government. Australia bought billions of gallons of water rights from farmers to recharge starving ecosystems, including the Murray River, which at one point ran dry at its mouth.

The changes had a rocky birth — at one meeting, thousands of farmers burned copies of the proposals. But the government’s purchase price for water rights was generous, and it came with a requirement that growers use the money to improve their irrigation systems. Many farmers found they could grow just as much — and make just as much money at it — while using less water.

That’s how it played out for Rocky Varapodio, who grows 500 acres of fruit in the country town of Ardoma. He sold 2.6 million gallons of his annual water rights toward the end of the drought to the government for $25,000, and the drip irrigation, timer and soil moisture sensors he installed enabled him to cut his yearly usage by 5 million gallons.

“We used to manually open our water valves and let the water run through the channels into our crop rows until it looked about right,” Varapodio said while he inspected his arrow-straight rows of apple and pear trees. “But now we have sensors planted into the soil that say exactly when enough water has been absorbed, and computerized controls then turn off the valves.

“We still use common farmer sense, but it doesn’t hurt to have a little help from science, too,” he said.

A few miles away in Wyuna, dairy farmer Russell Pell got the same deal on a bigger scale. He keeps 1,300 cows on 2,000 acres, and he sold his rights to 32 million gallons of the water to the government for $316,000.

With modernized channel controls tied to soil sensors, and new grading he was able to carve onto his pastures to more evenly distribute his irrigation, Pell saved 63 million gallons of water a year.

“We did well, and the next time a drought comes, I reckon we’ll feel even better,” Pell said. He straddled one of his irrigation canals to check one of the timing clocks, then nodded in satisfaction. “Stuff always works right now,” he muttered.

Cows stand in a field on Russell Pell's dairy farm, Pell Family Farms in Wyuna, Victoria, Australia on September 1, 2015.Eriver Hijano/Special to the Chronicle

Cows stand in a field on Russell Pell's dairy farm, Pell Family Farms in Wyuna, Victoria, Australia on September 1, 2015.Eriver Hijano/Special to the Chronicle

“Water is the golden goose, not just here in Australia but everywhere,” Pell said. “When you have it, everyone does well.”

Kevin Fagan is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. E-mail: [email protected] Twitter: @KevinChron

0 General Document comments

0 Sentence and Paragraph comments

0 Image and Video comments

New Conversation

Not sure about this. There are probably some who might advocate that the Great Salt Lake could be a potential drought solution, but an 8/26/20 article in the Salt Lake Tribune warns of damaging the Great Salt Lake’s ecosystem any further: https://www.sltrib.com/news/environment/2020/08/26/report-great-salt-lake/ And who knew the Brine Shrimp industry accounts for $1.3 billion economic activity annually.

New Conversation

Hide Full Comment

New Conversation

making an economic argument. Looks like it can pay off in one year

New Conversation

Hide Full Comment

A commercial building using 90% less than a comparable one is impressive on an economic scale, in addition to saving lots of water.It does make me wonder why the water we use to wash our hands isn’t just used for watering lawns, for example.

New Conversation

Hide Full Comment

A big part of urban planning is anticipating the future. For how Utah is approaching this, see Envision Utah’s Water Recommendation Strategy: https://envisionutah.org/utah-water-strategy-project

New Conversation

Hide Full Comment

General Document Comments 0