A Grassroots Call to Ban Gerrymandering

Author: Erick Trickey

Trickey, E. (2018, October 9). A grassroots call to ban gerrymandering. The Atlantic. Retrieved October 29, 2021, from https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2018/09/a-grassroots-movement-in-michigan-has-gerrymandering-in-the-crosshairs/570949/.

LANSING, Michigan—Katie Fahey walks in to the Grand Traverse Pie Company, blocks from the state capitol, wearing a black T-shirt that announces her cause. voters should choose their politicians, it reads, not the other way around.

As Fahey steps to the counter to order lunch, the cashier, a 20-something like her, recognizes the message. Last year, he tells her, he signed the initiative petition circulated by Voters Not Politicians to ban gerrymandering.

“We got almost a half a million people to sign,” enthuses Fahey, who founded the group in 2016 based on her viral Facebook post.

“That’s for the midterms?” asks the cashier’s co-worker.

“Yeah! So, Yes on 2, November 6!” Fahey says. “We just need 2 million voters. It’s fine! We got this.”

Fahey’s bravado is both sincere and ironic. An improv troupe founder and a mile-a-minute talker, the short-statured, dark-haired 29-year-old projects an idealistic energy that helped inspire thousands of volunteers through a massive, low-budget petition drive. She’s also wittily understating her group’s mammoth task ahead—and its high stakes for democracy, in Michigan and beyond.

Voters Not Politicians’ efforts have pushed Michigan, a swing state that swung to Donald Trump in 2016, to the forefront of the national movement to fight gerrymandering, the manipulation of election maps for partisan advantage. Michigan is the largest of four states voting in November on proposed changes to how voting districts are drawn after each census. A win in Michigan, one of the most gerrymandered states in the nation, could be a turning point for the growing effort to end partisan redistricting one state at a time.

It won’t be easy. But Voters Not Politicians’ volunteer army, led by Fahey, has already taken its effort further than the state’s political insiders thought possible.

The crowdsourced campaign held 33 town-hall meetings in 33 days, wrote a ballot proposal to give redistricting powers to a citizens’ commission, and fanned out across Michigan with clipboards and petitions in hand. Last fall, Voters Not Politicians volunteers collected 425,000 petition signatures in four months to secure a spot on Michigan’s ballot—a rare feat, usually accomplished only by hiring paid signature gatherers.

This fall they’re tackling a new set of challenges to redeploy their canvassers to get out the vote, fund-raise for TV ads, explain a complex proposal, channel Democrats’ anger against Michigan’s Republican gerrymander, and convince Republicans to support their proposal as a swamp-draining reform. Despite the group’s pledge not to work for any party’s advantage, conservative opponents have already tried to label the campaign a stalking horse for Democrats’ ambitions. But polls show it’s winning support across the political spectrum.

“Nobody feels like their politicians are listening to them,” Fahey says. “People want to drain the swamp. They want the political revolution … A lot of people understand that politicians [are] going to be politicians, and that them being able to control the outcome of elections doesn’t make sense.”

On election day 2016, Fahey, then 27, left her job at a recycling nonprofit in Lansing and rushed to the airport, thinking she’d witness history. A friend had an extra ticket to Hillary Clinton’s election watch party in New York City, and Fahey, who’d voted for Clinton that morning, thrilled at the invitation to go. “I could watch the first woman president find out she won,” Fahey remembers thinking.

RECOMMENDED READING

-

Instead, Fahey got to Midtown Manhattan in time to watch Donald Trump’s upset victory unfold. She was standing among other Clinton supporters at the Jacob K. Javits Convention Center in Manhattan, still dressed in the red pantsuit she’d worn to work, when a reporter captured her reaction.

“My disappointment makes me not trust the rest of the world,” Fahey told the Associated Press reporter that night. “I don’t even want to go out. I want to wear sweatpants and curl myself up in a corner.”

Afterward, Fahey says, she thought of her Millennial friends, who’d enthused over Bernie Sanders in 2016, and her parents, who’d grown excited about Trump. “I don’t want to wait four years and the next presidential election for them to stay engaged,” she recalls thinking. She dreaded Thanksgiving with her parents, fearing she’d end up in an argument about Trump and Clinton. “At Thanksgiving dinner, I wanted to talk about fixing stuff, and not candidates or political parties,” she recalls.

Fahey had never been involved in a political campaign, though she exhorted her friends to vote and had talked about her support for Clinton in conversation and enthusiastic Facebook posts. But she’d passed on attending Michigan State University to study sustainable business and community leadership at Aquinas College, a Dominican liberal-arts college in Grand Rapids that weaved Catholic social teaching into its curriculum. “If I see something not happening, I’m not afraid to go jump in and fix it,” she says. In the fall of 2016, Fahey was working full-time at the Michigan Recycling Coalition, studying for an M.B.A., and running two comedy troupes and the Grand Rapids Improv Festival. “I’m kind of a doer,” she says.

Two days after the election, Fahey went on Facebook. “I’d like to take on gerrymandering in Michigan,” she posted. “If you’re interested in doing this as well, please let me know.” She’d learned about gerrymandering in school—in fourth grade, in fifth grade, in 10th grade, in a public-administration class at Aquinas—and it had angered her each time.

“Redistricting,” Fahey says, “is one of the basic building blocks of democracy. It determines how 10 years of elections at a time will end up. And yet we know it’s corrupt and broken, and we don’t do anything about it.”

Her post spread fast. Friends shared it in political Facebook groups. Strangers responded, offering help. Fahey set up a Facebook group of her own, Michiganders for Nonpartisan Redistricting Reform, and asked members to pledge to support a solution that didn’t benefit any individual or party. Organized with Google Sheets, conference calls, and its first in-person meeting in January 2017, the group grew. By February it had chosen a catchier name, Voters Not Politicians. It held 33 town-hall meetings in 33 days, starting in Marquette and Alpena, northern Michigan cities that often get less political attention.

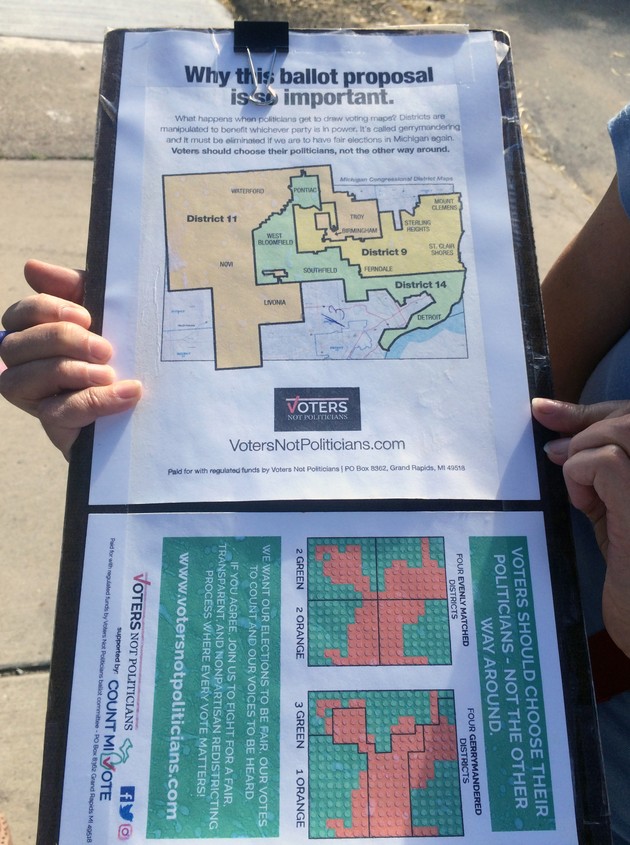

Voters Not Politicians’ canvassers carry clipboards with a map of gerrymandered congressional districts on the back. (Erick Trickey) It’s not always easy to get people riled up about gerrymandering, but Michigan proved fertile for a grassroots revolt against it. The state is closely divided politically, yet ever since a Republican-controlled redistricting in 2011, the GOP has enjoyed a 9–5 dominance of the state’s congressional delegation and large majorities in the state legislature. The congressional map in metro Detroit includes some especially freakish shapes: the Eleventh District looks like a sleeping vulture, the Fourteenth a bearded man meditating next to a crocodile’s jaws. Emails sent in 2011 between GOP congressional staffers, consultants, and the Michigan Chamber of Commerce, recently disclosed in a lawsuit, make the mapmakers’ partisan bias clear. “We’ve spent a lot of time providing options to ensure we have a solid 9–5 delegation in 2012 and beyond,” a chamber executive wrote.

Between 3,000 and 6,000 people came to Voters Not Politicians’ 33 town halls, Fahey says. They filled out surveys that asked if they wanted politicians to draw district lines, and if not, what process they’d prefer. Framing the question that way steered the group toward creating a citizens’ redistricting commission, as in California and Arizona. Specifics were hammered out in two in-person meetings of about 50 people, with others joining online via Google Docs and Trello. “Anyone who wanted to be at the policy table could be,” Fahey says: “a birthing doula, a lawyer, teachers, a caterer, pastor, veterinarian, an HR lawyer.”

The group took advice from Kathay Feng, the executive director of California Common Cause, who helped create her state’s citizens’ redistricting commission in 2008. It also ran its draft by possible future allies, including the League of Women Voters, the NAACP, and the ACLU, to ensure it conformed to their endorsement criteria for redistricting reform.

Its proposal would amend Michigan’s constitution to create a 13-member redistricting commission made up of regular citizens: four Republicans, four Democrats, and five independents or members of minor parties. People would apply to join, and the commissioners would be randomly selected from among the qualified applicants, though legislative leaders would be able to strike a few names from the list. To keep political insiders off the commission, the proposal bans partisan elected officials, candidates for partisan offices, lobbyists, political consultants, members of party governing committees, state employees outside civil service, and their close relatives from serving on the commission.

More importantly, Fahey says, the proposal would embed fairness in redistricting into the state constitution. “We directly make gerrymandering illegal,” she says. (“Districts shall not provide a disproportionate advantage to any political party,” the proposal reads. “Districts shall not favor or disfavor an incumbent elected official or a candidate.” )

But as Voters Not Politicians prepared to circulate petitions, it got discouraging advice. Conventional wisdom often claims that initiative petitions can’t get enough signatures to make the ballot with a volunteer petition drive alone—it takes paid signature gatherers. “There were a bunch of groups who were like, ‘You guys are crazy. We don’t want to work with you or endorse you yet, because you can’t do it,’” Fahey says. “I said ‘No! We’ve done the math.’”

The group had 180 days to gather 315,000 signatures in a state of 10 million people. “We had a plan,” the field director Jamie Lyons-Eddy says. “We needed 3,000 people to get 10 to 15 signatures a week.” Between social-media recruits and town-hall attendees who signed up to volunteer, 4,000 people ended up circulating petitions. Lyons-Eddy split the state into 14 regions, with about 10 petition teams in each. Still an online-only group with no physical offices, it crowdsourced ideas on where to get people to sign. Highway rest stops proved especially fruitful. One woman collected 80 signatures while dressed up as the gerrymandered Eleventh District.

Costs were about one-tenth of what the conventional wisdom expected: The biggest expenses were $40,000 to print the petitions and $140,000 to have a consultant verify the petitions, much of it chipped in by the volunteers themselves. The group turned in 425,000 signatures, 70 days early. In July, the proposal survived a challenge at the Michigan Supreme Court, which ruled 4–3 that it fit in the structure of the state constitution.

Fahey thinks the keys to the group’s success were taking on a systemic reform, inviting people to help write the ballot language, making the group easy to join, and having enthusiastic volunteers, not paid workers, convincing people to sign.

“I can actually impact the changes I’ve been wanting to see through direct democracy,” Fahey says, “not through a politician who’s maybe making a bunch of promises and not delivering.”

Late in august, denise yezbick walks through Detroit’s middle-class Palmer Woods neighborhood, holding an oversize clipboard. An adjunct English professor with gray-blond hair that reaches her shoulders, she’s got a Voters Not Politicians button pinned to her purse strap.

Yezbick knocks at a small Tudor Revival house. Matthew Weiner opens the door, wearing a blue T-shirt, gray shorts, and sandals. She asks if he’s heard of Proposal 2. He’s not sure, so she delivers a two-minute pitch for Voters Not Politicians’ proposal.

“This is your voting district, Fourteen, here,” Yezbick says, holding up the back of her clipboard to show a map of the zig-zagging congressional district. “And the reason it’s this crazy shape—”

“Crazy,” Weiner agrees.

Yezbick is careful to sound nonpartisan. “Both Republicans and Democrats abuse the system,” Yezbick says. “It just so happens we’ve got Republicans in power right now.” But as she says Republicans squeezed as many Democrats as possible into the Fourteenth to make surrounding districts less competitive, she’s got a receptive audience in Weiner, for reasons beyond good-government reform.

Denise Yezbick (right) and Linda Johnson canvass in the Palmer Woods neighborhood of Detroit. (Erick Trickey) “I’m against gerrymandering,” Weiner tells Yezbick, “and I’m a Democrat.” His mother-in-law recently read the book Ratf**ked, which describes how Republicans took control of redistricting in many states by targeting key elections in 2010.

0 General Document comments

0 Sentence and Paragraph comments

0 Image and Video comments

New Conversation

Hide Thread Detail

New Conversation

New Conversation

New Conversation

New Conversation

New Conversation

General Document Comments 0