The Case for Reparations in Tulsa, Oklahoma: A Human Rights Argument

Author: Dreisen Heath, Researcher/Advocate, US Program

Heath, Dreisen. “The Case for Reparations in Tulsa, Oklahoma.” Human Rights Watch, 28 Oct. 2020, https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/05/29/case-reparations-tulsa-oklahoma.

Summary

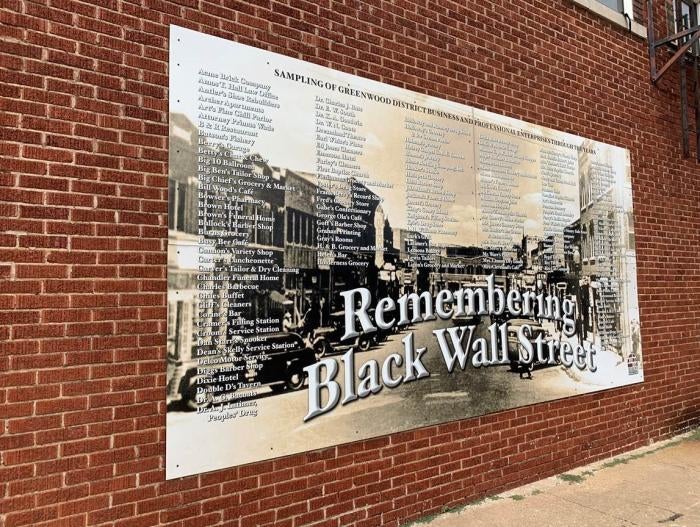

In the span of about 24 hours between May 31 and June 1, 1921, a white mob descended on Greenwood, a successful black economic hub in Tulsa, Oklahoma then-known as “Black Wall Street,” and burned it to the ground. Some members of the mob had been deputized and armed by city officials.

In what is now known as the “Tulsa Race Massacre,” the mob destroyed 35 square blocks of Greenwood, burning down more than 1,200 black-owned houses, scores of businesses, a school, a hospital, a public library, and a dozen black churches. The American Red Cross, carrying out relief efforts at the time, said the death toll was around 300, but the exact number remains unknown. A search for mass graves, only undertaken in recent years, has been put on hold due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Those who survived lost their homes, businesses, and livelihoods. Property damage claims from the massacre alone amount to tens of millions in today’s dollars. The massacre’s devastating toll, in terms of lives lost and harms in various ways, can never be fully repaired.

Following the massacre, government and city officials, as well as prominent business leaders, not only failed to invest and rebuild the once thriving Greenwood community, but actively blocked efforts to do so.

No one has ever been held responsible for these crimes, the impacts of which black Tulsans still feel today. Efforts to secure justice in the courts have failed due to the statute of limitations. Ongoing racial segregation, discriminatory policies, and structural racism have left black Tulsans, particularly those living in North Tulsa, with a lower quality of life and fewer opportunities.

On the 99th anniversary of the massacre, a movement is growing to urge state and local officials to do what should have been done a long time ago—act to repair the harm, including by providing reparations to the survivors and their descendants, and those feeling the impacts today.

Under international human rights law, governments have an obligation to provide effective remedies for violations of human rights. The fact that a government abdicated its responsibility nearly 100 years ago and continued to do so in subsequent years does not absolve it of that responsibility today—especially when failure to address the harm and related action and inaction results in further harm, as it has in Tulsa. Like so many other places across the United States marred by similar incidents of racial violence, these harms stem from the legacy of slavery.

There are practical limits to how long, or through how many generations, such claims should survive. However, Human Rights Watch supports the conclusion of the Oklahoma Commission to Study the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921 (recently renamed the Tulsa Race Massacre Commission)—a commission created by the Oklahoma state legislature in 1997 to study the massacre and make recommendations—that reparations should be made.

The Tulsa Race Massacre occurred in a broader context of racist violence and oppression stemming from slavery, which continues to impact black people in the United States today. Human Rights Watch has long been supportive of the development of broader reparations plans to account for the brutality of slavery and historic racist laws that set different rules for black and white people. Accordingly, Human Rights Watch supports US House Resolution 40 (H.R. 40), a federal bill to establish a commission to examine the impacts of the transatlantic slave trade and subsequent racial and economic discriminatory laws and practices. H.R. 40 has been circulating in Congress for 30 years but recently gained renewed momentum given a growing public understanding about the harms of slavery and its continuing impact today. The bill garnered nearly 100 new co-sponsors in the House just last year; a companion bill in the Senate, S. 1083, has 16 co-sponsors.

After decades of silence, an enormous amount has been written in recent years about the Tulsa massacre and its aftermath, including many books,[1] and a comprehensive 200-page report, known as the “Tulsa Race Riot Report,” issued by the “Tulsa Race Riot Commission” in 2001.[2] Yet the state and local governments involved have failed to take action.

In the run-up to the massacre’s centennial, the Tulsa and Oklahoma governments should finally take meaningful steps to repair these ongoing, devastating wrongs.

Methodology

This report is largely based on research, as well as an analysis and review, of materials conducted from March through May 2020. These include the 2001 “Tulsa Race Riot Report,” numerous books on the massacre and its aftermath, news articles, law review articles, academic research papers, court records, and city planning documents. It also contains a lightly edited reprinting of several sections of an extensive 216-page Human Rights Watch report “Get on the Ground”: Policing, Poverty and Racial Inequality in Tulsa, Oklahoma,[3] released in September 2019, which documents in detail systemic racial disparities in in Tulsa today.

In addition, we also conducted six interviews with members of the Tulsa community, including descendants of victims of the massacre or individuals involved in racial justice efforts in Tulsa. These interviews built upon the substantial body of research, including 132 interviews, we had conducted for Get on the Ground. We conducted most of the new interviews by phone or by video due to restrictions on travel related to the Covid-19 pandemic. All interviewees gave their full informed consent to the interviews and were provided no incentives to participate.

All documents cited in this report are publicly available or are on file with Human Rights Watch.

The Greenwood Massacre and its Legacy[4]

On May 31, 1921, police in Tulsa arrested Dick Rowland, a young black man who lived in the Greenwood section of town, for an alleged assault on a white woman.[5] Though the evidence against him was not strong,[6] the Tulsa Tribune printed an editorial that afternoon calling for a lynching.[7] A mob of white men converged on the county lock-up.[8]

At the time, lynching of black people was common throughout the US—61 were reported in 1919; 61 in 1920; and 57 in 1921.[9] Violent white mobs terrorized and attacked black people, killing them and destroying their property, in cities throughout the US.

When news of the lynch-mob reached Greenwood, community members, including many World War I veterans, armed themselves and went to the courthouse to protect Rowland, but the sheriff told them to leave.[10] After the black men left, the crowd outside the courthouse grew to over two thousand, many of them armed.[11] Tulsa police made no effort to de-escalate the situation or disperse the crowd.[12]

Later that night, the men from Greenwood returned, offering to help the sheriff protect Rowland.[13] A fight broke out when a white man tried to disarm one of the black veterans trying to protect Rowland[14] and some shooting began, lasting through the night.[15]

Early the next morning, a large mob of white men and boys invaded Greenwood, outnumbering its defenders by 20 to 1 or more.[16] Witnesses said that people in airplanes flew over Greenwood dropping firebombs and shooting at people.[17]

The attack lasted throughout the day. The mob drove through Greenwood, shooting and killing black people, looting and burning their homes and businesses.[18] Many black residents fought back, but they were greatly outnumbered and outgunned. Many fled, while thousands were taken prisoner.[19] At best, Tulsa Police took no action to prevent the massacre. Reports indicate that some police actively participated in the violence and looting.[20]

The mob destroyed 35 square blocks of Greenwood, burning down over 1,200 homes, over 60 businesses, a school, a hospital, a public library, and a dozen churches.[21] Hundreds of homes that were not burned down were looted as well.[22] Some estimates put the death toll at 300,[23] while others believe it was much higher.[24]

The Tulsa City Commission issued a report two weeks after the massacre saying: “Let the blame for this negro uprising lie right where it belongs—on those armed negros and their followers who started this trouble and who instigated it and any persons who seek to put half the blame on the white people are wrong …”[25]

The Massacre’s Aftermath

In the early morning hours of June 1, 1921, Oklahoma Governor James A. Robertson called in National Guard troops and declared martial law.[26] The National Guard, as well as local law enforcement and other white citizens deputized by them, [27] began disarming and arresting all black people and moving them to internment camps located at the Convention Hall, the McNulty Baseball Park, or the fairgrounds.[28] This internment facilitated destruction and death, leaving black residents, outnumbered by more than 20 to 1,[29] without the ability to defend their lives, home, and property.[30]

During the attack, white men dragged dozens of black people in their nightclothes from their beds on the white side of town, in homes where they lived as domestic workers, screaming at and severely beating them before hauling them off to internment at various locations downtown.[31] Others liberally spread kerosene or gasoline inside Greenwood homes and businesses and then lit them on fire.[32] Once in the camps, black Tulsans were not able to leave without permission of white employers.[33] When they did leave, they were required to wear green identification tags.[34] By June 7, 7,500 tags had been issued.[35] The American Red Cross, which ran the internment camps, reported that thousands of black Tulsans, then homeless, were forced to spend months, or in some cases over a year and through the winter, in the camps, in tents.[36] Many suffered disease and malnutrition in the camps.[37] During a six-month period after the violence began, the Red Cross reported “eight definite cases of premature childbirth that resulted in the death of babies” and that “of the maternity cases given attention by Red Cross doctors, practically all have presented complications due to the riot.” [38]

The Tulsa Race Massacre Commission confirmed in its report that Tulsa officials, and the hundreds of whites they deputized, participated in the violence—at times providing firearms and ammunition to people, all of them white—who looted, killed, and destroyed property.[39] It also found that no one was ever prosecuted or punished for the violent criminal acts.[40]

When Governor Robertson visited Tulsa on June 2, he ordered that a grand jury be empaneled and put the attorney general S.P. Feeling in charge.[41] All of the 12 men selected for the panel on June 9, 1921 were white.[42] After several days of testimony the jury indicted more than 85 people[43]—the majority black—[44] mostly for rioting, carrying weapons, looting and arson.[45] Most of the indictments were ultimately dismissed or not pursued, including the indictment against Rowland, as the complaining witness never came forward.[46]

One of the only indictments that was pursued was that against John Gustafson, the white Tulsa police chief who was accused of neglect of duty, and charges unrelated to the massacre—freeing automobile thieves for which he collected rewards.[47] After a two-week trial that garnered significant press attention, he was convicted, sentenced to a fine, and fired.[48] According to James Hirsch, who wrote a book about the massacre and its aftermath, Gustafson’s conviction had the effect of granting “blanket immunity” to all the white people who murdered and looted.[49] In charging Gustafson, the prosecutor made clear that she did not believe any of the white people who armed themselves had violated the law. Rather, she said:

After those armed Negros had started shooting and killed a white man—then those who armed themselves for the obvious purpose of protecting their property and lives violated no law. The [police] chief neglected to do his duty and the citizens after seeing their police fail, took matters into their own hands.[50]

The final 1921 grand jury report blamed Black people for the massacre: “There was no mob spirit among the whites, no talk of lynching and no arms. The assembly was quiet until the arrival of the armed Negros, which precipitated and was the direct cause of the entire affair.” [51] The grand jury report also named another cause: “agitation among the Negros of [sic] social equality.” [52]

The exact number of people killed has been hard to establish, in part because after the attack began, the Oklahoma National Guard commanding general, Charles Barrett, issued an order denying funerals for the deceased on the ground that he claimed churches were already overwhelmed with helping the displaced.[53] To this day no one knows what happened to most of the bodies, though there is reason to believe at least some were buried in mass graves. An investigation into this possibility, after being dormant for years, was recently reopened (see below).[54]

Initially, some Tulsa officials acknowledged the wrongdoing and promised restitution and repair. “Tulsa can only redeem herself from the country-wide shame and humiliation … by complete restitution of the destroyed black belt…Tulsa weeps at this unspeakable crime and will make good the damage … down to the last penny, ” said Judge Loyal J. Martin, chairman of the Executive Welfare Committee, a body formed on June 2, 1921 through the Tulsa Chamber of Commerce in response to the violence and for the purpose of rehabilitating the city.[55] Alva J. Niles, president of the Chamber of Commerce, made similar apologies and promised that “rehabilitation will take place and reparation made,” adding that Tulsa feels “intensely humiliated,” and pledged to “punish those guilty of bringing the disgrace and disaster to this city.” [56]

These promises were never realized. Some city and county resources went to fund immediate American Red Cross relief efforts to provide temporary shelter, food, and medical assistance to some of the thousands displaced.[57] However, government officials committed no public money to help Greenwood rebuild—in fact, they worked to impede it, and even rejected offers of medical and reconstruction assistance from within and outside Tulsa.[58] In the end, the restoration of Greenwood after its systematic destruction was left entirely to the victims of that destruction.[59]

Obstacles to Rebuilding

An estimated 11,000 black people lived in Tulsa before the massacre, most in the Greenwood area (see maps of the Greenwood District’s historic boundaries in Appendix A).[60] Appendix A

When black Tulsans tried to rebuild, they faced enormous obstacles, including hostility from powerful sectors of the city: an illustrative June 4 Tulsa Tribune editorial titled “It Must Not Be Again” stated: “the old ‘Niggertown’ must never be allowed in Tulsa again.” [61] Many of the white men who participated in the attack occupied prominent positions at City Hall, the community’s courthouses, press rooms, churches, and office buildings.[62]

The “Tulsa Race Riot Commission” retrieved court filings for 193 lawsuits filed against the city and insurance companies for property and other losses totaling about $1,470,711 in 1921.[63] This likely underestimates material losses, as not everyone in Greenwood had insurance and of those who did, not all took insurance companies or the city to court.[64] All the claims pursued were dismissed,[65] despite Gustafson’s conviction, which did not translate into any benefit or restitution for the victims.[66]

Insurance companies denied claims based on “riot exclusion” clauses in the contract.[67] Claimants argued in vain that the violence was not caused by a riot but by law enforcement action, inaction, and negligence.[68]

Many also filed claims worth $1.8 million at what the “Tulsa Race Riot” report said was called the “City Commission.” [69] All were denied, except for one filed by a white pawnshop owner for $3,994.57 for ammunition taken from his shop during the violence.[70] The “Tulsa Race Riot Commission” used the $1.8 million figure instead of the $1,470,711 to estimate property losses, noting that this figure would be worth nearly $17 million in 1999 dollars. Using the commission’s same method of calculation—that figure would be worth more than $25 million today.[71] Others have put the value of property loss claims alone at between $50 to$100 million in today’s dollars.[72]

On June 7, 1921, the Executive Welfare Committee[73] announced its intention to direct a body called the “Real Estate Exchange” to develop a plan to value the properties burned down in the Greenwood area and purchase them from black owners with an eye towards relocating black residents and turning the area into an industrial and wholesale district.[74] The Real Estate Exchange’s leadership ranks included W. Tate Brady, a known member of the Ku Klux Klan,[75] and the plan—though never realized—had the support of some white civic organizations, businessmen, and “political elements.” [76]

On the same day, the City Commission passed a Fire Ordinance that required any new structures in Greenwood to be at least two stories high and be made of concrete, brick, or steel.[77] The ordinance effectively prevented many black Tulsans from rebuilding because such materials were prohibitively expensive.[78] Most of the Greenwood houses that burned down were wood-framed.[79] Tulsa Mayor T.D. Evans supported the ordinance, suggesting a railroad and railroad station be built in the area: “Let the negro be placed farther to the north and east,” he said, urging the commissioners to get in touch with the railroads as soon as possible.[80] Merritt J. Glass, the Real Estate Exchange president, argued that building a railroad station in Greenwood “will draw more distinctive lines between them and thereby eliminate the intermingling of the lower elements of the two races … the root of all evil which should not exist.” [81]

From a makeshift tent office on Archer Street,[82] B.C. Franklin, who escaped his burning law office during the massacre, and a group of his associates brought a case challenging the zoning ordinance. The case, Joe Lockard v. the City of Tulsa, demanded that Joe Lockard, owner of a wood framed house “on Lot seventeen (17) in Block two … in the City of Tulsa” that had been burned down during the massacre,[83] be able to build on his property and that the ordinance be enjoined.[84] Ultimately, they won. In September 1921, the Oklahoma Supreme Court found the ordinance unconstitutional because it would deprive Greenwood property owners of their property rights if they were not able to rebuild.[85]

Black Tulsans did manage to rebuild for a time, despite the hostility of powerful sectors of the city and state. They also did so at their own expense, with no assistance or restitution for the lives or property lost and at the cost of other opportunities they had to forgo, such as investments in education, health, or other business ventures.

Greenwood Rebuilds, Subsequent Decline

Starting in the early 1930s and 40s, Greenwood began to thrive again as a prosperous economic center. The “Tulsa Race Riot Commission” report describes this renaissance:

The tragedy and triumph of North Tulsa transcends numbers and amounts and who owned what portion of what lot. The African American community not only thrived in an era of harsh “Jim Crow” and oppression, but when the bigotry of the majority destroyed their healthy community, the residents worked together and rebuilt. Not only did they rebuild, they again successfully ran their businesses, schooled their children, and worshiped at their magnificent churches in the shadow of a growing Ku Klux Klan in Oklahoma and continuing legal racial separatism for more than forty years. In fact, one of the largest Ku Klux Klan buildings, not only in the state, but the country [sic] stood within a short walking distance of their community.[86]

A local business directory, compiled by the Greenwood Chamber of Commerce sometime after the beginning of World War II, describes the area as “unquestionably the greatest assembly of Negro shops and stores to be found anywhere in America” and lists hundreds of businesses.[87] The introduction to the directory states:

Perhaps nowhere else in America is there a single thoroughfare which registers such significance to local Negros as North Greenwood Avenue in Tulsa. Today, after some twenty-five years of steady growth and development, Greenwood is something more than an Avenue, it is an institution. The people of Tulsa have come to regard it as a symbol of racial prominence and progress—not only for the restricted area of the street itself, but for the Negro section of Tulsa as a whole.

However, black people in Tulsa were still living in a system that was heavily biased against them. With no restitution or reparation for the harms done to them, and ongoing racial disparities in access to education, health, housing, and other social and economic rights and benefits, the cards were stacked against Greenwood’s ongoing success.

Ultimately, a complex set of factors that included government policies that disproportionately burdened black people resulted in Greenwood’s long-term decline. These included federal redlining and “urban renewal” programs pursued by the city and state.

Redlining

As a part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC),[88] established in 1933, embarked on a City Survey Program,[89] using data from mortgage lenders and real estate developers, to investigate real estate conditions and assess desirability of neighborhoods.[90] The program resulted in a series of color-coded maps in 239 cities, including Tulsa, Oklahoma.[91] Neighborhoods were graded with one of four categories from green (“the best”) to red (“hazardous”).[92] Local mortgage companies deemed “redlined” areas, comprised of mostly low-income minorities, to be credit risks, making it impossible for many residents to access mortgage loans, furthering the homeownership and wealth gap.[93]

Thirty-five percent of Tulsa, including parts of the historic Greenwood District and surrounding areas, was deemed hazardous by the HOLC.[94] While the 1968 Fair Chance at Housing Act outlawed redlining and other racially discriminatory housing practices, the effects of that racial and economic segregation persist today.[95] A 2018 study shows that most of the neighborhoods that the HOLC marked as “hazardous” between 1935 and 1939 are low-income and minority neighborhoods today.[96]

A recent strategy document by the City of Tulsa recognizes that “historical actions including redlining and exclusionary zoning have led to disinvestment in neighborhoods that were once thriving in Tulsa.” [97] Additionally, a 2018 analysis of publicly available data under the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act found that black Tulsans were 2.4 times more likely to be denied home mortgage applications than white applicants in Tulsa.[98]

“Urban Renewal”

Greenwood’s decline was further accelerated by “urban renewal”[99]—a set of federally financed policies aimed at rehabilitating areas considered blighted by such methods as condemning property and paying occupants to move or using eminent domain, and then redeveloping the land.[100] Urban renewal helped to clear areas of downtown Tulsa including the northeast corridor of downtown, part of the Greenwood neighborhood.[101]

By the early 1970s, these policies had claimed and demolished so many businesses and homes in Tulsa, more than 1,000, many of them in Greenwood, that black Tulsans would come to call urban renewal “urban removal,” according to Hirsch.[102] This led black Tulsans to move north, east, and west—but with few exceptions, not to the more prosperous neighborhoods south of the railroad tracks.[103]

Highway construction projects, which sought to “redeem” urban areas, disproportionately low-income and black, were a significant aspect of the urban renewal era.[104] Beginning in the 1950s, the city condemned property in areas including Greenwood, forcing the residents to move, in order to build seven expressways, funded mostly by the federal government,[105] to build the Inner Dispersal Loop (IDL), which formed a ring around downtown.[106] Completed in the 1970s, the north side of the IDL cut a high concrete swath along the southern boundary of Greenwood while the elevated Cherokee Expressway runs along the eastern edge of Greenwood. Two highways bound the remaining population in Greenwood’s core and created dead space under the overpasses and near the exits.[107] It also displaced many families and businesses.[108]

A May 4, 1967 article in the Tulsa Tribune about how Greenwood had changed, said:

The crosstown expressway slices across the 100 block of North Greenwood Avenue, across the very buildings that [were] once “a mecca for the Negro businessman” … There will still be a Greenwood Avenue, but it will be a lonely, forgotten lane ducking under the shadow of a big overpass.[109]

Other property targeted by the Tulsa Urban Renewal Authority includes the site where Oklahoma State University (OSU-Tulsa) now sits, which is where Booker T. Washington High School, Greenwood’s main high school before the massacre, was located.[110] According to the “Tulsa Race Riot Commission’s” report, “urban renewal and the accumulation of North Greenwood property for the highway and Rogers State University (now OSU-Tulsa), create a gap in the records of property and cause old addresses, legal and otherwise, do [sic] not display on the county clerk computer system.” [111]

Hirsch concludes that highway construction and urban renewal, combined with other economic factors, resulted in Greenwood’s economic collapse. The outcome, he wrote, was in “eerie parallel to what the city had tried to do after the riot: drive blacks away from downtown Tulsa.” [112]

Tulsa historian Hannibal Johnson notes that if it were not for the efforts of the massacre survivors, like E.L. Goodwin Sr., who by the 1970s owned Greenwood’s last remaining law practice and had acquired several other Greenwood properties, what is left of Greenwood might not exist.[113] The Tulsa Urban Renewal Authority targeted Goodwin’s property but he refused to sell unless he got outright title, or an option to purchase the remaining buildings on the once-famous Greenwood Avenue. The Tulsa Urban Renewal Authority agreed.[114] Thanks to the efforts of Goodwin and others, Hannibal writes, the 100 block of Greenwood Avenue, located between Archer Street and the Interstate 244 overpass remains somewhat preserved “but it is a skeleton of its former self” when it was home to 242 black-owned and operated businesses in a 35-square-block area.[115] Goodwin’s brother, James, later reflected:

What was characteristic of urban renewal authorities across the country, was that right through the core of the black business community, like an arrow through the heart, came the expressways. It happened here, in Oakland, Chicago and a host of other cities.[116]

A report by Tulsa’s Neighborhood Regeneration Project in 1978 described Greenwood as a place “that is left today [with] generally abandoned and underutilized buildings, sitting in a sparse population of poor and elderly black[s] awaiting the relocation counselors of the Urban Renewal Program.” [117] And according to a 1985 article in The Oklahoman, “by 1979, little remained of the original district but a few boarded-up brick buildings at Greenwood and Archer and a small group of businessmen who comprised the Greenwood Chamber of Commerce.” [118]

Tulsa Today

Poverty, Race, and Geography

(This section through “The Fight for Reparations and Economic Justice in Tulsa” are adapted from the Human Rights Watch Report “Get on the Ground: Policing, Poverty and Racial Inequality in Tulsa, Oklahoma,” September 2019, pp. 12-13, 30-48).[119]

The effects of the Greenwood massacre and subsequent discrimination continue to be felt in the present day. Black neighborhoods remain underdeveloped and under resourced. Mistrust of police is a legacy of the massacre. Aggressive policing in the present serves as a reminder and even an extension of the past.

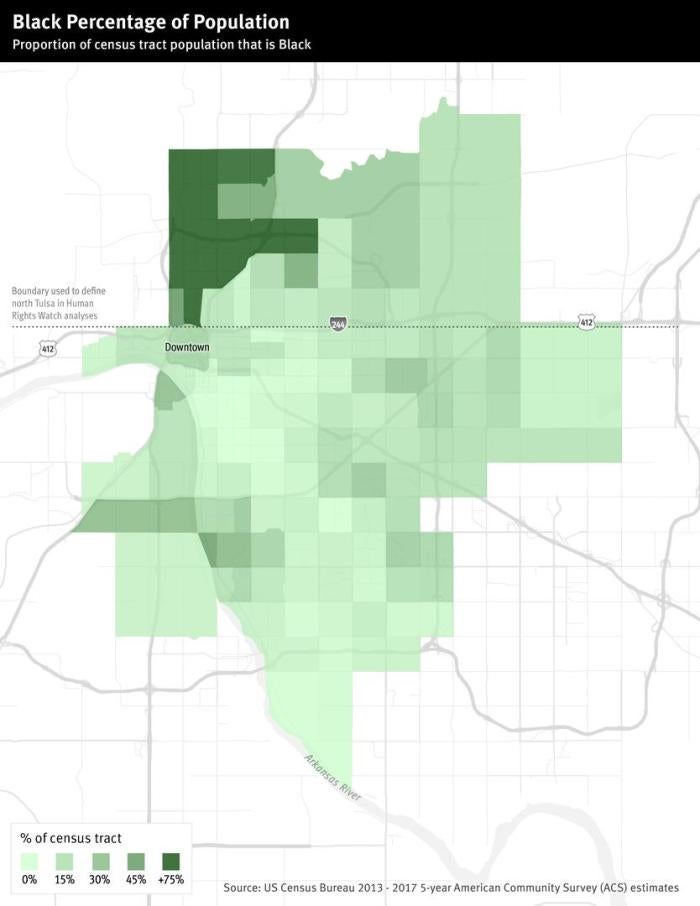

Large percentages of black people in Tulsa live in North Tulsa, above the 244 Freeway and Admiral Boulevard, and in smaller enclaves throughout the city like the area around 61st and Peoria Street, which has a large number of public housing projects.

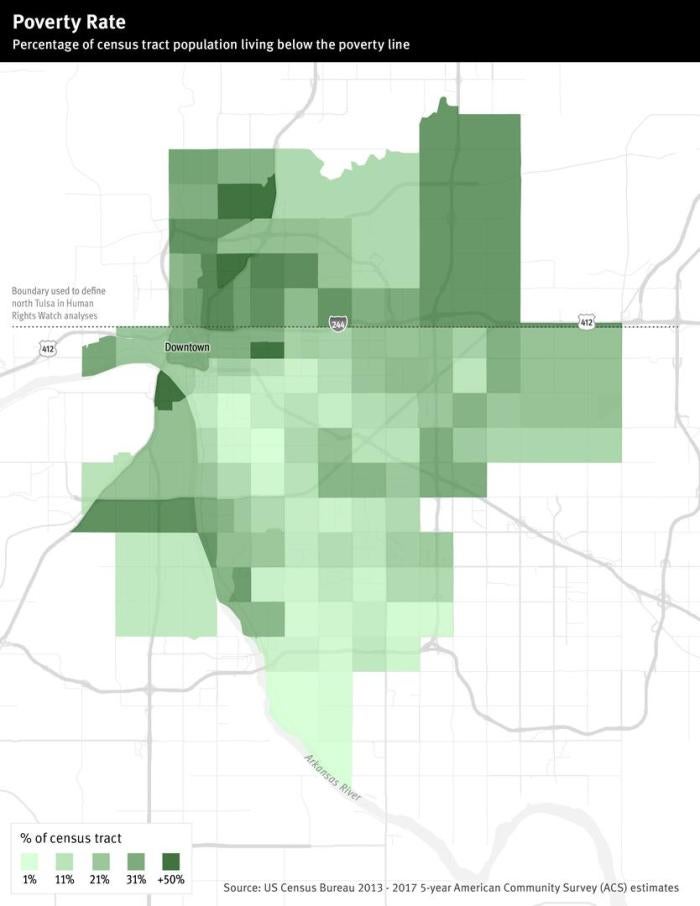

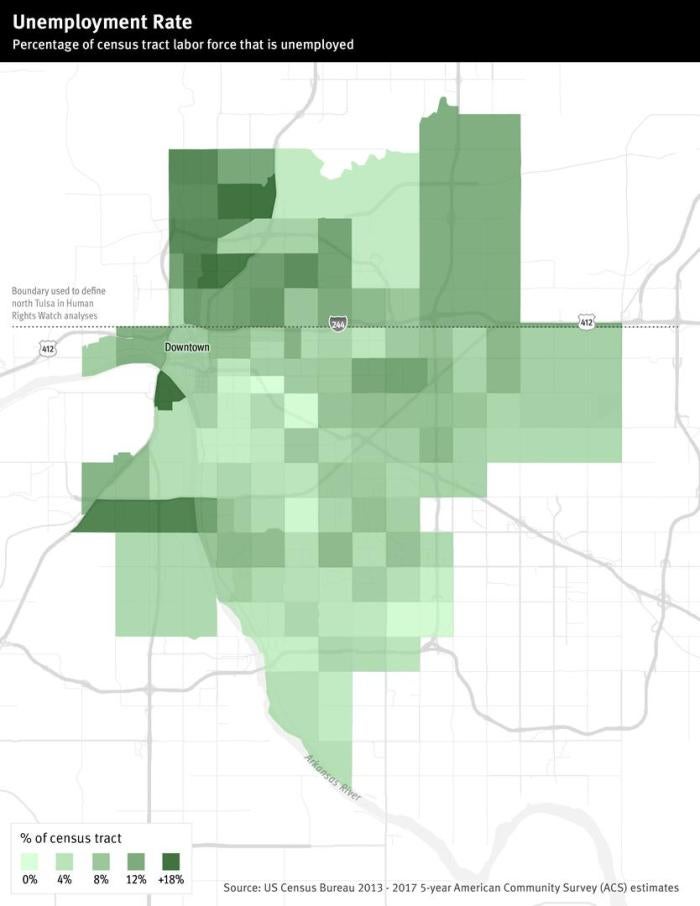

The geographic segregation tends to track poverty rates. North Tulsa is significantly poorer than other parts of the city. There are few businesses and few large-scale employers there. Investment in the community has been greatly lacking. Some 33.5 percent of North Tulsans live in poverty, compared to 13.4 percent in South Tulsa. Unemployment overall for black people is 2.4 times the rate for white people. There are huge differences in life expectancy between north and south. North Tulsa has no traditional supermarkets with fresh meats and produce, and it is hard to find nutritious foods. Schools in Oklahoma, in general, are underfunded and in crisis. Tulsa schools are extremely segregated, with black students far more likely to be in schools characterized by high rates of poverty and high absenteeism, drop-out, and turnover rates. Black students are suspended from school much more frequently than white students.

As of mid-2019, Tulsa Mayor GT Bynum had recognized these significant inequalities and was taking important steps to address them. However, the city budget remained tilted towards policing. Over one-third of the city’s general fund was going to the police department, whose budget continued to grow. The city recently approved an additional sales tax to pay for a major expansion of the police department.

The racial and class dynamics of modern-day Tulsa exist in the context of a highly segregated city.[120] Racial divisions and economic underdevelopment, particularly in North Tulsa, contribute to crime, which serves as a rationale for aggressive police activity. Imposition and enforcement of criminal debt takes money from poor people and people of color in Tulsa, who tend to be poor, draining resources from their families and communities.

The poverty and lack of economic development of North Tulsa result from a variety of factors, including historical neglect dating back to the destruction of Greenwood in 1921. Reverend Gerald Davis of The United League for Social Action (TULSA) said that there is a great deal of investment in economic development in South Tulsa, including street improvements, bus lines, sewer lines, and other infrastructure, but politicians tend to ignore North Tulsa.[121] A prevalent attitude among people with political and economic power is “you don’t want to go there, build there, buy there.” [122]

Davis attributes this neglect, in large part, to “systemic racism,” and says that it has persisted from the time of legalized racial segregation.[123] Systemic or structural racism is caused by public policies, institutional practices, cultural representations, and other norms working in various, often reinforcing, ways to perpetuate racial group inequity.[124] These policies, practices and norms serve to benefit and privilege white people while denying basic rights and limiting opportunities for people of color. Systemic racism does not depend on racism of individuals or on overt discriminatory intent, but it can exist even in a culture that disavows racial bias.

Many community leaders from North Tulsa agree on the need for structural change in the neighborhoods where crime occurs, including investment in education, job training, infrastructure, business development, entrepreneurship, and employment opportunities, not more abusive policing.[125]

Poverty, race, and geography correlate substantially in Tulsa. The line dividing North Tulsa from the rest of the city is often recognized as Admiral Place and Interstate 244, which run alongside each other east to west across the city.[126] About half of all black people in Tulsa live in North Tulsa, though this section only has 21 percent of the city’s total population.[127] The seven zip codes identified[128] as comprising North Tulsa have a total population of approximately 85,000 people according to recent census data.[129]

The median yearly household income for this entire area is $28,867.[130] By contrast, the six zip codes identified with South Tulsa have a total population of just over 127,000 people, and a median yearly household income almost double, at $59,908. Median household income for black households throughout Tulsa is below $30,000; it is above $50,000 for white households.[131]

Just over one-third of people living in North Tulsa are below the poverty line, and 35.7 percent are black.[132] Just 13.4 percent of South Tulsans are below the poverty line, and only 9.1 percent of South Tulsans are black. In North Tulsa, 36 percent of the black population and 32 percent of the white population are below the poverty line.[133]

Individual zip codes within North Tulsa that have higher percentages of black residents also have higher poverty rates. Zip code 74106 is made up of 67.2 percent black residents. It has the highest poverty level of any Tulsa zip code at 41 percent.[134] Zip code 74126, just north of 74106, has the second highest percentage of black residents in Tulsa at 57.2 percent, and has a poverty level of 38.5 percent. In contrast, South Tulsa zip code 74137, with only 3.1 percent black residents, has only 7.6 percent of its population living in poverty. Overall, the black population of North Tulsa is about 48,700; the white population is 48,400.

Data from 2017 shows that white people made up 38 percent of all people living in poverty in Tulsa; black people were 20.7 percent; Latinos, 18.2 percent; people identified as multi-racial, 9.1 percent and Native Americans, almost 3.9 percent.[135] However, the poverty rate for black people throughout the city is about 33.5 percent, while the rate for white people is just under 13 percent.[136]

North Tulsa has relatively few businesses and shopping districts, compared to other parts of the city.[137] They tend to be small and do not provide many employment opportunities.

According to a city study on inequality, South Tulsa had a two-and-a-half times greater presence of small businesses per resident than North Tulsa; East Tulsa’s rate was almost double.[138] The study found that North Tulsa had many payday lenders, which typically carry extortionate rates of interest that often keep poor people trapped in debt, and few banks that might invest in community development.[139] North Tulsa has large numbers of dilapidated residential and commercial properties.[140]

According to the city study, North Tulsa had the lowest labor force participation and fewest jobs of any region of the city.[141] Overall unemployment, defined as the rate of individuals participating in the labor force but unable to find work, is 2.37 times higher for black than for white Tulsans.[142] The unemployment rate in North Tulsa only is 14 percent for black people and 11 percent for white people.[143]

Crime and law enforcement impact economic opportunities. People with criminal records face serious barriers to getting jobs.[144] Those coming out of jail or prison have few options and are often burdened by court-imposed debt that can result in further arrest for failure to pay, and loss of employment opportunities.[145]

Health

Tulsa’s racial and economic class segregation is reflected in differences in “quality of life” factors between different sections of the city. A 2015 study conducted by Virginia Commonwealth University’s Center on Society and Health found the lowest life expectancy in Tulsa in the poorest areas with the greatest concentration of black residents.[146]

The North Tulsa zip code 74106, with the city’s highest percentages of black population and of residents living in poverty, had an average life expectancy of 70 years.[147] South Tulsa zip codes 74133 and 74137, both with poverty rates below 10 percent and black populations at 7.5 percent and 3.1 percent respectively, had average lifespans of 81 years.[148]

Throughout Tulsa, infant mortality rates for black people are almost triple that for white people.[149] Rates of heart disease are considerably higher, and rates of low birth weight children are nearly twice as high for black people as for white people. [150]

“Social and economic factors are well known to be strong determinants of health outcomes,”[151] according to the St. Johns Health System community needs assessment, which identified nearly all of the North Tulsa zip codes as locations in Tulsa County with the greatest need.[152]

Nutrition

Nutrition and access to nutritious food is an important contributing factor to the overall health of an individual and a community. The state of Oklahoma as a whole suffers from a high rate of food insecurity, with 15.5 percent of all households lacking sufficient nutrition, significantly higher than the national average.[153] Food insecurity and hunger, most prevalent in impoverished communities, increase illness and health-care costs, decrease academic achievement and weaken the labor force, all exacerbating the existing poverty.[154]

“Food deserts are geographic areas where grocery stores are scarce and are void of fresh produce, usually found in low-income areas.” [155] About 19 percent of Tulsa County residents live in areas considered “food deserts,”[156] and 45 percent of Tulsa’s population have low access to nutritious food.[157] The areas considered food deserts are primarily in North Tulsa.[158]

Lack of Grocery StoresInstead of grocery stores with adequate supplies of fresh produce, North Tulsa has “Dollar” convenience stores that primarily sell processed foods with little nutritional value.[159] Activists in North Tulsa, including City Councilor Vanessa Hall-Harper, have called for regulations to limit the number of these stores.

Hall-Harper and the Tulsa Economic Development Corporation are spearheading an effort to use Community Development Block Grant money to develop a traditional grocery store in a central North Tulsa location.[160]

Residents of North Tulsa now must drive great distances to get healthy food.[161] Some do not own cars, while many that do are not able to afford extra gas.

Some have had their licenses suspended due to warrants or criminal court debt.

Driving exposes people to aggressive police enforcement tactics.

Education

Oklahoma schools are underfunded; Oklahoma teacher pay ranked ahead of only Mississippi and South Dakota in 2016;[162] 20 percent of the state’s schools were reduced to four-day weeks in 2018 due to budget cuts.[163] The Tulsa schools lost 628 teachers in the 2016-2017 school year, due in large part to low salaries.[164] Schools lack adequate funding for textbooks and repairs.[165]

Over the past decade, Oklahoma schools have lost 30 percent of their funding, adjusting for inflation.[166] The state legislature cannot raise taxes without a three-quarters majority,[167] making it extremely difficult to raise revenue through taxation.

Inadequate school funding negatively impacts low-income schools much more than those with wealthier student populations.[168] Local schools raise money from their communities and benefit from parents contributing for supplies, sports, music programs, and other activities to enrich the lives of students. Schools in very low-income communities, such as North Tulsa, lack this alternative source of income.

Along with segregated neighborhoods come segregated schools. The Tulsa area has 12 schools with greater than 75 percent black enrollment, 19 schools with greater than 50 percent black enrollment, mostly in the city of Tulsa, and 71 schools, almost all in suburban school districts, with less than 6 percent black enrollment.[169]

The percentage of students eligible for free and reduced school lunches is often used as a proxy for the percentage of its students living in poverty. The average black student in Tulsa public schools attends a school where over 81 percent of students are eligible for free and reduced school lunch, as compared to 77 percent for the average Latino student, and 55 percent for the average white student.[170]

High poverty schools have much greater rates of absenteeism and students are more likely to leave after one year than are students at predominantly white lower poverty schools.[171] Turnover and interruption in attendance in a school make it difficult for all students to learn,[172] and reflect the stresses of poverty that greatly impact scholastic achievement, including poor health, hunger, and exposure to crime and violence.[173]

Black students receive school suspensions at a rate 2.5 times greater than white students, and at a significantly greater rate than Latino students.[174] Despite recent policy changes to de-emphasize removing children from school,[175] which have reduced overall suspensions,[176] there remain significant differences in suspension, dropout, and mobility rates based on race and wealth.[177]

These educational deficiencies, all problems in Tulsa’s under-resourced, low-income public schools, are likely contributors to crime,[178] as young people who fail in school have fewer economic opportunities, are more likely to be unemployed, lack legal options for survival, and have to deal with other stresses that accompany poverty.[179]

Police Funding in Tulsa

Tulsa devotes much of its budget to policing. Policing has accounted for about one-third of the outlays from the general fund, the city’s primary operating fund,[180] over the past five years, and accounts for by far the largest general fund outlays. By contrast, “public works and transportation” made up about 10 percent of the budget in FY18-19, and social and economic development about 4 percent. [181]

When city revenues dropped significantly in FY 2014-2015, the mayor had other city departments take cuts to allow for increases in the police department.[182] Both city[183] and county[184] authorities have recently put public money into building, renovating, expanding, and operating jails.[185]

The Fight for Reparations and Economic Justice in Tulsa

The 1921 “Tulsa Race Riot Commission”

For generations, the 1921 race massacre was absent from Oklahoma history books.[186] It was deliberately covered up and eventually disappeared from the memories of succeeding generations outside the Greenwood and North Tulsa districts.[187] “Oklahoma schools did not talk about it. In fact, newspapers didn’t even print any information about the Tulsa Race Riot,” US Senator James Lankford of Oklahoma said. “It was completely ignored. It was one of those horrible events that everyone wanted to just sweep under the rug and ignore.” [188]

In fall 2020, for the first time, the Oklahoma Education Department is adding the 1921 Tulsa race massacre to its curriculum.[189] Over the past several decades, members of Tulsa’s black community, some descendants or relatives of descendants of the massacre, many of them now living in other parts of North Tulsa, and other community leaders, have been mobilizing to memorialize the Greenwood massacre, obtain some measure of justice for the survivors and others harmed, and repair the damage that was done.

When formed in 1997, the 11-member “Tulsa Race Riot Commission” was charged with “developing an historical record of the Tulsa Race Riot,” including identifying witnesses, gathering documents, and obtaining physical evidence.[190] They identified 118 survivors and at least another 176 descendants of massacre victims.[191] The report concluded “these were not any number of multiple acts of homicide; this was one act of horror … reparations are the right thing to do.” [192]

The commission recommended that the state legislature, the Governor, the Tulsa mayor, and the city council take the following actions:

- Make direct payment of reparations to “riot” survivors and descendants;

- Create a scholarship fund available to “students affected by the riot;”

- Establish an economic development enterprise zone in the historic Greenwood district;

- Create a memorial for the riot victims and for the burial of any human remains found in the search for unmarked graves of riot victims.[193]

Most of these recommendations have not been realized. To the extent some of them have, they have been mostly funded by private actors. The commission had no legislative authority. Following the release of the commission’s report, Oklahoma state legislators passed the “1921 Tulsa Race Riot Reconciliation Act.” [194] This Act adopted many of the findings of the “Tulsa Race Riot Commission,” recognizing that claims that the massacre was due to a “negro uprising” were incorrect, and acknowledging that a “conspiracy of silence” served the “dominant interests of the state,” which was eager to attract new business and settlers and for which the massacre was a “public relations nightmare.” [195] Subsequently, the legislature also created a memorial fund that could receive private and public resources for the purpose of creating a memorial run by the Oklahoma Historical Society,[196] and the Greenwood Area Redevelopment Authority, to “facilitate the redevelopment of the Greenwood area”[197] as well as a scholarship fund,[198] but little public money has been appropriated to maintain those entities.[199] None of the legislation provided financial compensation to survivors or descendants of survivors of the massacre.

The Call for Reparations and Legal Justice

The Tulsa Reparations Coalition (TRC) was formed on April 7, 2001,[200] and led a campaign to seek reparations through a possible lawsuit[201] and to convince the government, at minimum, to fully implement the “Tulsa Race Riot Commission’s” recommendations.[202] They received endorsements for their call to action from individuals and organizations across the United States.[203]

In the fall of 2001, then-Oklahoma Governor Frank Keating rejected the state’s culpability in the massacre and maintained the position that Oklahoma state law prohibited reparations from being administered on the state’s behalf.[204] In a letter to the TRC, Governor Keating wrote: “I have carefully reviewed the findings of the Tulsa Race Riot Commission and, contrary to the statement in your letter, I do not believe that it assigns culpability for the riot to the state.” [205] The Commission’s report does, in fact, document actions by the National Guard that contributed to the massacre.

Subsequently, the TRC enlisted the support of the Reparations Coordinating Committee,[206] a group of lawyers seeking to administer legal reparatory justice.[207] In 2003, nearly two years after the “Tulsa Race Riot Commission” issued its final report, a legal team—including Charles Ogletree Jr., Johnnie Cochran Jr., and other prominent US civil rights lawyers—sued the city of Tulsa, the Tulsa Police Department, and the state of Oklahoma on behalf of more than 200 survivors and descendants of victims of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre.[208]

Lawyers argued that the survivors and descendants were entitled to “restitution and repair,” for the injuries due to the action or inaction of Tulsa and Oklahoma officials during and following the massacre.[209] Specifically, they alleged that they had been physically or emotionally injured or that their relatives had been killed, and that they or their relatives, had personal property that was burned, looted, or otherwise destroyed. They held the defendants responsible because they “routinely under-investigated, under-responded, undercharged, mishandled and failed to protect Plaintiffs from a series of criminal acts or prosecute those responsible for such acts.” [210]

The US District Court for the Northern District of Oklahoma dismissed the case based on the statute of limitations. The plaintiffs acknowledged that Oklahoma’s two-year statute of limitations for civil actions applied but argued that a “conspiracy of silence” surrounding the massacre and its aftermath delayed the accrual of their claims until issuance of the “Tulsa Race Riot Report” in February 2001.[211] The court found that extraordinary circumstances sufficient to toll the statute of limitations existed. These included: a limited ability to obtain facts, fear of a repeat of the “riot,” inequities in the justice system, Ku Klux Klan domination in the courts, and the Jim Crow era. However, finding “no comfort or satisfaction in the result,” it held that those circumstances dissipated in the 1960s.[212] Later that year, an appellate court affirmed that opinion, noting that it too took “no great comfort” in the decision, and that sometimes statutes of limitations “make it impossible to enforce what were otherwise perfectly valid claims.” [213] In 2005, the US Supreme Court declined to hear the case without comment.[214]

Despite these setbacks, descendants of the survivors of the massacre, their relatives, and others, continue to press their claims for justice. Authorities are also taking some steps to address the massacre’s legacy. In 2017, as the 100th year since the Tulsa massacre approached, Tulsa Mayor G.T. Bynum and Oklahoma US Senator Kevin Matthews, announced the formation of the Tulsa Race Massacre Centennial Commission.[215]

The Centennial Commission delegated responsibility to five unique committees to develop meaningful initiatives for Greenwood residents;[216] they worked with Tulsa Public Schools to develop a curriculum on the Tulsa Massacre and sponsored the installation of a Black Wall Street Mural near the Greenwood Cultural Center.[217] This center, opened in 1995, offers educational and cultural programming, and describes itself as the “keeper of the flame for the Black Wall Street era.” [218] One of the Centennial Commission’s main projects for the district is the Greenwood Cultural Center’s renovation and expansion. The Greenwood Rising History Center, originally designed to be constructed next to the Greenwood Cultural Center, will now be built on the corner of Greenwood and Archer, thanks mostly to private donations (including a land donation), as well as state funding and money from local taxes.[219]

Reverend Robert Turner of the historic Vernon African Methodist Episcopal (AME) church, damaged in the massacre, embarks on a reconciliatory pilgrimage of sorts from Vernon AME to Tulsa City Hall every Wednesday, demanding “reparations now.”

[220] Turner and others support the reintroduction of a bill, H.R. 98, the John Hope Franklin Tulsa-Greenwood Race Riot Claims Accountability Act, initially introduced in the US House of Representatives in 2013, which would create a new federal cause of action for harms resulting from the deprivation of rights during the Tulsa race massacre or its aftermath against responsible parties for five years following passage of the Act.[221] They also support a petition calling on the state to pass legislation to clear legal hurdles to civil lawsuits related to the 1921 massacre.[222]

In May 2021, the Tulsa Community Remembrance Coalition will erect the first comprehensive, public memorial honoring the victims of the 1921 massacre on the grounds of Vernon African Methodist Episcopal (AME) church, which has since been rebuilt.[223] The memorial will be funded entirely by private donations.[224]

In 1998, consultants to the commission began a limited investigation into the potential presence of mass graves at three locations.[225] In 1999, a white man who was 10 at the time of the massacre came forward to say that after the massacre he saw white men digging trenches near one of the three locations, Oaklawn Cemetery, and that when he peaked inside crates nearby he saw the charred bodies of black men.[226] Based on this information, further investigation was authorized but not pursued directly after the commission issued its report. [227] In 2018, after being questioned about a report published in the Washington Post, [228] exposing unresolved questions surrounding the massacre and the failure to investigate the existence of mass graves,[229] Mayor Bynum said he would restart it.[230] In early 2020, investigators were scheduled to begin excavation in the area of Oaklawn Cemetery but at the time of this writing it had been postponed due to the Covid-19 pandemic.[231]

The Tulsa Chamber of Commerce has recently apologized for its actions in the wake of the massacre; it also donated copies of minutes from its 1921 meetings to the Greenwood Cultural Center.[232]

Tulsa’s Economic Development Plans

Tulsa has undertaken programs supposedly aimed at revitalizing and developing economic opportunities in the Greenwood area. In 2009, former Tulsa Mayor Kathy Taylor, announced the development of “ONEOK Field,” a minor league baseball stadium, aimed at continuing the “redevelopment of downtown Tulsa and the revitalization of the historic Greenwood District.” [233]

Current Tulsa Mayor Bynum is supporting a plan to bring a BMX Olympic arena and headquarters to Greenwood, a plan he says will bring job and other opportunities to black Tulsans in the area.[234] The plan includes significant public funding.[235] When asked about reparations, Mayor Bynum said he prefers to focus attention on the money that the city is putting into building and development of areas near historic Greenwood.[236]

But community members do not necessarily agree that this approach will help them. North Tulsa and Greenwood community leaders have raised concerns that businesses and political leaders developing the Greenwood area are not doing enough to preserve black culture in the historic area,[237] making it unaffordable for many black Tulsans, and not prioritizing economic opportunities for them.[238] J. Kavin Ross, from the Oklahoma Eagle Newspaper, a black-owned publication that has been located in Greenwood since 1936, described survivors and descendants having to withstand the legacy of displacement in Tulsa, especially in Greenwood.[239] “With gentrification—we say, now you want to take an interest in Greenwood and pimp our history? And you are going to build these apartments down here, and you know darn well we are not going to spend $1,000 for a closet room,” Ross said. “We will never be able to afford to live in Greenwood.” [240]

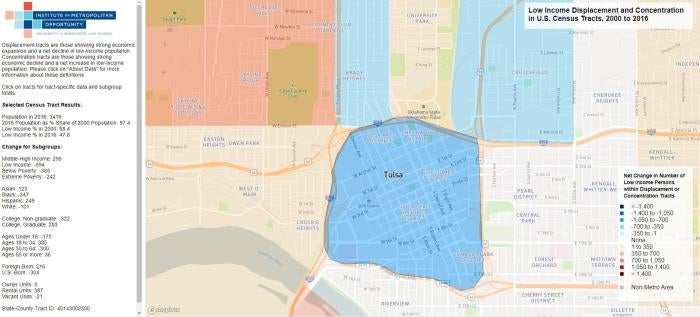

According to data analysis by the Institute on Metropolitan Opportunity at the University of Minnesota Law School (see below), there are net declines in low-income populations (at or below 200 percent of the federal poverty line), as well as the black population, in the historic Greenwood district, downtown Tulsa, and surrounding areas a little further north and east—including the Tulsa Arts and Blue Dome districts.[241] The analysis also shows areas further north and east in Tulsa have higher concentrations of low-income people.[242] The data suggests that Greenwood’s residents are being displaced to areas further from downtown and out of the historic Greenwood District.[243]

Ricco Wright, owner of the Black Wall Street Gallery near historic Greenwood,[244] said the new coffee shops, boutiques, and new cycling studio, are examples of “gentrification that has infringed upon the Greenwood District over the years and slowly robbed the area of its once proud African American history.” [245]

In 2019, hundreds of residents attended a meeting at which city council members discussed recent development plans for North Tulsa—labeled the “Greenwood-Unity Heritage Neighborhoods Sector Urban Renewal Plan” —that apparently included plans to take some property in the area by eminent domain.[246] So many people showed up for the meeting that Fire Marshals prevented people from entering as they would have exceeded the building’s 217-person capacity. Scores of angry residents stood in the lobby outside the chamber, and crowds remained outside the doors of city hall itself.[247] North Tulsa residents expressed opposition to the city’s amended plans to use eminent domain to seize their property, displacing residents.[248]

Brenda Nails-Alford, a resident of North Tulsa who attended the meeting, said that her ancestors lost their property in the 1921 race massacre and, again, during urban renewal efforts. She said she feared being displaced from her current home: “as a third-generation to uphold it, I am very, very upset that [the Tulsa Development Authority] want[s] to take it,” she said. “It is the one thing that you left us, and we will not give it up.” [249]

After the meeting, the Tulsa Development Authority (TDA) suspended its plans.

The Greenwood Chamber of Commerce, a local non-profit organization, is trying to raise $1 million to preserve the last 10 buildings of the original Black Wall Street on Greenwood Avenue.[250] The National Park Service recently awarded the non-profit $500,000 toward their fundraising goal as a part of their grant initiative to preserve black sites and history across the United States.[251]

However, in 2018, members of the Black business community established the Black Wall Street Chamber of Commerce (BWSCC) as an alternative to the Greenwood Chamber of Commerce, which they felt was not meeting their needs.[252] Founders also aimed to bolster black entrepreneurship in the area and help rebuild Black Wall Street.[253] Tulsa City Councilor Vanessa Hall-Harper, also Membership Committee & Power Group Chair for the BWSCC,[254] told the Tulsa World that she and others started the BWSCC to raise money to rebuild Black Wall Street and the surrounding North Tulsa community. The funds raised will be “used to buy back land based on the wants and needs of the community.” [255] Many are hopeful for an authentic rebuilding and economic development effort, but others say too much damage has been done to Black Wall Street and Greenwood to revive it back to the thriving hub it once was.[256]

The historic Greenwood district offered proof that black people could create economic opportunity, in the shadows of systematic oppression and white supremacy. Greenwood’s restoration was left in the hands of massacre survivors nearly 100 years ago and today their descendants and other community members are left fighting to preserve what is left.

Thus far, the city’s recent development efforts have fallen short of delivering on promises of economic benefits for Tulsa’s black citizens. Without significant and concrete actions and investment, informed by the community’s wishes, to repair the cumulative losses of the black community in Tulsa, the legacy of the massacre and its aftermath will persist.

International Human Rights Law and Past Reparations Examples

Right to an Effective Remedy and the Tulsa Race Massacre

The United States is a party to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD), both of which guarantee the right to an effective remedy for human rights violations, including acts of racial discrimination.[257]

This right requires that governments ensure access to justice, truthful information about the violation, and reparation.[258]

Victims of gross violations of human rights, like the Tulsa Race Massacre, should receive full and effective reparations that are proportional to the gravity of the violation and the harm suffered.[259] The failure to provide such a remedy itself does continuing harm. As noted in the preamble to the United Nations Basic Principles and Guidelines on the Right to a Remedy and Reparation for Victims of Gross Violations of International Human Rights Law and Serious Violations of International Humanitarian Law, “in honouring the victims’ right to benefit from remedies and reparation, the international community keeps faith with the plight of victims, survivors and future human generations and reaffirms the international legal principles of accountability, justice and the rule of law.” [260]

Reparation includes the following:

- Restitution: measures to restore the situation that existed before the wrongful act(s) were committed, such as restoration of liberty, employment and return to the place of residence and return of property.[261]

- Compensation: monetary payment for “economically assessable damage” arising from the violation, including physical or mental harm, material losses, and lost opportunities.[262]

- Rehabilitation: provision of “medical and psychological care as well as legal and social services.” [263]

- Satisfaction: includes a range of measures involving truth-telling, statements aimed at ending ongoing abuses, commemorations or tributes to the victims, and expressions of regret or formal apology for wrongdoing.[264]

- Guarantees of non-repetition: includes institutional and legal reform as well as reforms to government practices to end the abuse.[265]

States should “provide reparation to victims for acts or omissions which can be attributed to the State and constitute gross violations of international human rights law.” [266]

The Tulsa Race Massacre and surrounding events led directly to the loss of hundreds of lives, loss of liberty, substantial personal and business property loss, and damage to objects of cultural significance. Compounding inequalities stemming from the massacre led to lower life expectancy, increased need for mental health services, loss of economic opportunity, and other harms to community members over decades.

Yet the victims of the massacre have yet to receive an effective remedy.

Existing judicial mechanisms have failed to provide that remedy in part due to the statute of limitations. But international human rights standards provide that such statutes of limitations should not be unduly restrictive—applying a statute of limitations to limit remedies in cases of gross violations of human rights is particularly problematic.[267]

The local and state governments have also failed to provide effective remedies to the victims for the harm suffered due to the government’s role in the massacre, as provided by international standards.[268] To the contrary, the “Tulsa Race Riot Commission” report, as well as other sources, document numerous instances where city and state officials intentionally blocked social and economic restoration efforts in the aftermath of the massacre for black Tulsans in North Tulsa, including Greenwood.

In situations where those responsible cannot or will not provide reparation, governments—in this case including the US government—should endeavor to establish reparation programs and support victims.[269]

According to the UN special rapporteur on contemporary forms of racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia, and racial intolerance, “…historical violations continue [] to impede the enjoyment of human rights.” [270]

This has been the case in Tulsa, where the massacre and surrounding events set the stage for decades of systematic disinvestment in Greenwood and North Tulsa’s black and poor communities. Black and low-income people in Tulsa do not maintain an adequate standard of living and “reinvestment” efforts near and around the Greenwood area have contributed to the decline of social services, employment opportunities, affordable housing, access to medical care, and adequate access to food for black and low-income people who reside there.

The US federal government as well as state and local governments have made reparations in the past to victims of human rights violations.[271] The state of Florida issued reparations for survivors of a massacre[272] similar to Tulsa’s, as well as to their descendants.

Reparations for Slavery

The victims of the Tulsa Race Massacre deserve access to an effective remedy for the harms they have suffered. At the same time, it is important that the United States go beyond reparations in this specific case.

The Tulsa Race Massacre occurred in a context of systemic racism rooted in the US history of slavery, segregation, discrimination, oppression, and violence against black people. The massacre compounded the existing inequality in the system, doing devastating harm to the community, which, despite periods of regeneration and renewal, has never fully recovered—both due to the lack of any meaningful effort to remedy the harm, and because of ongoing systemic racism.

Before the abolishment of the international slave trade in 1808,[273] 400,000 Africans were sold into the United States.[274] The people killed in the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre were only some of the thousands of those killed in racial terror lynchings that took place in the US between the end of Reconstruction in 1877 and 1950. According to a report by the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), an estimated 4,300 racial terror lynchings took place during that time,[275] including those that occurred during the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre.[276] In the year 1919 alone, more than two dozen different incidents of racially motivated violence took place.[277] Even following the enactment of the emancipation proclamation in 1863, many US cities and states, including in the north, implemented laws and policies that legalized racial segregation and stripped Black people of their rights.[278]

The US government has never adequately accounted for these wrongs or the subsequent 20th century policy decisions that resulted in the structural racism, economic, education, and health inequalities, housing segregation, and discriminatory policing policies and practices, described above, that exists today.[279]

Human Rights Watch has long supported reparations to address the brutality of slavery and historical racist laws that set different rules for Black people and white people.[280]

Article 6 of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination (ICERD), establishes the right to remedy and to seek adequate reparation for acts of racial discrimination like slavery and the many crimes against Black people that have followed from it in the United States.[281]

But governments are also independently obligated to address structural discrimination. The UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, the UN body that interprets the ICERD and monitors compliance with it, has noted that “racism and racial discrimination against people of African descent are expressed in many forms, notably structural and cultural.” [282]

The committee added that this structural discrimination, rooted in slavery, is:

[E]vident in the situations of inequality affecting them and reflected, inter alia, in the following domains: their grouping, together with indigenous peoples, among the poorest of the poor; their low rate of participation and representation in political and institutional decision-making processes; additional difficulties they face in access to and completion and quality of education, which results in the transmission of poverty from generation to generation; inequality in access to the labour market; limited social recognition and valuation of their ethnic and cultural diversity; and a disproportionate presence in prison populations.[283]

States are obligated under ICERD to overcome this structural discrimination, including through “special measures” such as affirmative action.[284] Also, states are obligated to “[t]ake steps to remove all obstacles that prevent the enjoyment of economic, social and cultural rights by people of African descent especially in the areas of education, housing, employment and health.” [285]

As noted by the UN special rapporteur on contemporary forms of racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia, and racial intolerance in an August 2019 report to the UN General Assembly, “reparations for slavery and colonialism include not only justice and accountability for historic wrongs, but also the eradication of persisting structures of racial inequality, subordination and discrimination that were built under slavery and colonialism to deprive non-whites of their fundamental human rights.” [286] In that sense, “reparations concern both our past and our present.” [287]

The UN Working Group of Experts on People of African Descent also stated, upon the conclusion of a visit to the United States, that “past injustices and crimes against African Americans need to be addressed with reparatory justice.” [288]

Reparations should be based not just on past harms but on contemporary ones too—the question is how to do so fairly, timely, and equitably.[289]

At the national level, Human Rights Watch supports House Resolution (H.R.) 40,[290] which proposes creating a commission to study the impacts of slavery and make recommendations around “apology and compensation.” [291] This bill—titled “40” as a reminder of the never-fulfilled promise made to free slaves to give each “40 acres and a mule” after the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation[292]—has been circulating in Congress for the past 30 years. It has never been voted out of the House Judiciary Committee, where it has been introduced, but support for it is growing, demonstrated by the long list of co-sponsors, now at 126, all but one of them signing on in the last year.[293] The US Congress should pass H.R. 40, and the president should sign it into law.

Recommendations

The recommendations below to the Tulsa, Oklahoma, and US governments are primarily focused on the need for proportionate and prompt reparations for the massacre and its aftermath. However, they also touch upon broader reparations for slavery, and the obligation of governments to address ongoing structural racism.

Reparations for the Tulsa Race Massacre

The “Tulsa Race Riot Commission” made its recommendations to the state of Oklahoma and the city of Tulsa nearly 20 years ago, but they have yet to be fully implemented. The longer harms go unaddressed, the more difficult and complex it will be to develop adequate reparation mechanisms that are proportionate to the gravity of the crime and to the harm caused.

To the US Congress

Statute of Limitations

A member of the US Congress should reintroduce, and Congress should pass, legislation to clear the legal hurdle that the statute of limitations poses to the assertion of civil claims related to the Tulsa race massacre and its aftermath.[294]

To State and Local Authorities

Immediate Compensation to Survivors

At the time of writing,[295] Viola Fletcher, residing in Bartlesville, Oklahoma, who just celebrated her 106th birthday,[296] and Lessie Benningfield Randle, aged 105, living in Tulsa were the only known living survivors of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre living in Oklahoma. Neither they nor any descendants of survivors have ever received any restitution or compensation for the harm they suffered. A coalition of local organizations, including the Terence Crutcher Foundation, the Gathering Place, Revitalize T-Town, and other community members, recently restored Randle’s home in North Tulsa, but the project was paid for entirely out of private funds.[297]

Given Fletcher and Randle’s advanced age, the city and state governments should immediately take steps to provide reparation to them, including in the form of direct compensation and acts to recognize, memorialize, and apologize for the harm done.

Statute of Limitations

A member of the Oklahoma legislature should introduce, and the legislature should pass, legislation that would clear the legal hurdle that the Oklahoma statute of limitations now poses to civil claims related to the massacre and its aftermath. In addition, the state of Oklahoma and city of Tulsa should commit not to assert any statute of limitations defense in any claims brought against them in connection with the massacre so that the claims can be heard on the merits.

Recovery of Remains

State and local authorities should continue and fund the investigation into the existence of mass graves currently underway, recover, and identify the remains.

Promptly Develop and Implement a Comprehensive Reparations Plan

State and local authorities should move promptly to develop a comprehensive reparations plan, in close consultation with survivors, descendants, and community members affected by the massacre, that is based on the recommendations of the “Tulsa Race Riot Commission” report and responsive to developments in the last 20 years. Such a plan should include, as the commission recommended, direct payments to massacre survivors and their descendants. It should also include measures to further rehabilitation, truth-telling, and guarantees of non-repetition.

In designing such a plan, state and local authorities could consider the following measures, some of which community members have recommended:

Rehabilitation, Medical Benefits, and Burial Services

Authorities could offer rehabilitation for survivors and descendants, including free trauma-informed care as a result of the generational impacts of the massacre. The city of Tulsa could work with the Oklahoma Department of Health to issue lifetime medical benefits and burial services to all living survivors and descendants residing in Greenwood and North Tulsa.

Educational Benefits and Scholarships

The city and state should consider substantially expanding the limited existing scholarship award program.[298] One option would be to offer descendants of the massacre and students in the Greenwood and North Tulsa area tuition-free enrollment, especially at the two universities, that appear to have been built through the accumulation of North Greenwood property through urban renewal, Oklahoma State University-Tulsa and Langston University-Tulsa.[299] Authorities could also establish, with public funding, in consultation with the Tulsa African Ancestral Society, a birthright program, a free ten-day heritage trip to Africa, for descendants who want to deepen their historical and cultural connection to the African continent.

Economic Development and Investment in the Affected Community

There is great concern in Tulsa’s black community that existing economic development initiatives are not benefiting its members and may even cause further harm. Authorities should develop any plans in close consultation with community members.

Among other options, authorities could consider establishing a business development fund for black residents in Greenwood and North Tulsa and ensuring administration and decision-making for the fund includes leaders from the target communities, and includes a process for consultation with long-time residents. They could actively recruit Greenwood residents to apply for grants or provide community-based block grants for black applicants expressing interest in entrepreneurial activities. They could ensure that a certain percentage of grants benefit black entrepreneurs from Greenwood and North Tulsa.

Historical Memory

A privately funded $3 million campaign to construct Tulsa’s first comprehensive memorial is underway.[300] The city of Tulsa should consider financing the entire project or, at minimum, donating to the campaign.

The city of Tulsa should also consider providing capital endowments for future historical and arts exhibits that capture the full essence of thriving Greenwood, in addition to continuing and implementing plans for the renovation and expansion of the existing Greenwood Cultural Center. To preserve the history and culture of historic Greenwood, the Tulsa Preservation Commission and the Oklahoma Historic Preservation Review Committee could seek to establish Greenwood in the National Historic Registry.[301]

Housing

State and local authorities should consider:

- Providing subsidized housing, housing assistance, and housing relief services to residents displaced from Greenwood, who now reside in North or East Tulsa, or other parts of the county.

- Subsidizing home mortgages and rent for long-term residents of Greenwood.

- Issuing housing vouchers for long-time residents of the Greenwood community to help them stay in their homes when rising housing prices and property taxes increase the risk of displacing them.

Encourage Private Sector Support

State and local authorities could encourage other actors to support reparations as well. In particular, they could:

- Encourage the Tulsa Regional Chamber of Commerce (formerly the Tulsa Chamber of Commerce), to establish a free and public online database with searchable records from meetings, events, and other official activities, and to allocate significant funding to a reparations program for massacre survivors, descendants, and Greenwood residents.

- Encourage the Langston University-Tulsa (formerly Rogers State University) and OSU-Tulsa (formerly University Center at Tulsa) to provide records of acquisition and deed transfers of property acquired in the Greenwood area prior to the establishment of the universities and make those records public in order that full disclosure be made of property that was confiscated. These universities could also be encouraged to provide free meeting space for community meetings and events.

Addressing Ongoing Structural Racism and the Legacy of Slavery

To State and Local Governments

- Collect data and commission expert studies on persistent racial disparities in Tulsa and Oklahoma at large, respectively, in a variety of systems, including housing, health, education, criminal law, access to employment, and access to capital.

- Review government budgets to direct more resources to social and economic programs in low-income black communities that are impacted by long-term structural racism.

- Develop and implement programs in various systems—health, housing, education, and criminal law—that are specifically designed to counter the long-term effects of structural racism.

To the US Congress

- Pass House Resolution (H.R.) 40, the Commission to Study and Develop Reparation Proposals for African-Americans Act. The expert commission established by H.R. 40 should collect data and produce studies on persistent racial disparities in the United States at large, respectively in a variety of systems, including housing, health, education, criminal law, access to employment, and access to capital. Upon the termination of the commission, Congress should establish another body to collect and produce similar data and studies.