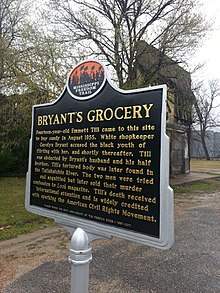

Till continues to be the focus of literature and memorials. A statue was unveiled in Denver in 1976 (and has since been moved to Pueblo, Colorado) featuring Till with Martin Luther King, Jr. Till was included among the forty names of people who had died in the Civil Rights Movement (listed asmartyrs[114]) on the granite sculpture of the Civil Rights Memorial in Montgomery, Alabama, dedicated in 1989. In 1991, a 7-mile (11 km) stretch of 71st Street in Chicago, was renamed "Emmett Till Road". Mamie Till-Mobley attended many of the dedications for the memorials, including a demonstration in Selma, Alabama on the 35th anniversary of the march over the Edmund Pettis Bridge. She later wrote in her memoirs, "I realized that Emmett had achieved the significant impact in death that he had been denied in life. Even so, I had never wanted Emmett to be a martyr. I only wanted him to be a good son. Although I realized all the great things that had been accomplished largely because of the sacrifices made by so many people, I found myself wishing that somehow we could have done it another way."[115] Till-Mobley died in 2003, the same year her memoirs were published.

James McCosh Elementary School in Chicago, where Till had been a student, was renamed the "Emmett Louis Till Math And Science Academy" in 2005.[116] The "Emmett Till Memorial Highway" was dedicated between Greenwood and Tutwiler, Mississippi, the same route his body took to the train station on its way to Chicago. It intersects with the H. C. "Clarence" Strider Memorial Highway.[117] In 2007, Tallahatchie County issued a formal apology to Till's family, reading "We the citizens of Tallahatchie County recognize that the Emmett Till case was a terrible miscarriage of justice. We state candidly and with deep regret the failure to effectively pursue justice. We wish to say to the family of Emmett Till that we are profoundly sorry for what was done in this community to your loved one."[118] The same year, Georgia congressman John Lewis, whose skull was fractured while being beaten during the 1965 Selma march, sponsored a bill that provides a plan for investigating and prosecuting unsolved Civil Rights era murders. The Emmett Till Unsolved Civil Rights Crime Act was signed into law in 2008.[119]

Casket

On July 9, 2009, a manager and three laborers at Burr Oak Cemetery were charged with digging up bodies, dumping them in a remote area, and reselling the plots. Till's grave was not disturbed, but investigators found his original glass-topped casket rusting in a dilapidated storage shed.[120] When Till was reburied in a new casket in 2005, there were plans for an Emmett Till memorial museum, where his original casket would be installed. The cemetery manager, who administered the memorial fund, pocketed donations intended for the memorial. It is unclear how much money was collected. Cemetery officials also neglected the casket, which was discolored, the interior fabric torn, and bore evidence that animals had been living in it, although its glass top was still intact. The Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C. acquired the casket a month later. According to director Lonnie Bunch III, it is an artifact with potential to stop future visitors and make them think.[113]

See also

Notes

-

Accounts are unclear; Till had just completed the seventh grade at the all-black McCosh Elementary School in Chicago (Whitfield, p. 17).

-

Some recollections of this part of the story relate that news of the incident traveled in both black and white societies very quickly. Others state that Carolyn Bryant refused to tell her husband and Till's oldest cousin Maurice Wright, perhaps put off by Till's bragging and clothes, told Roy Bryant at his store about Till's interaction with Bryant's wife. (Whitfield, p. 19.)

-

Several major inconsistencies between what Bryant and Milam told interviewer William Bradford Huie and what they had told others were noted by the FBI. They told Huie they were sober, yet reported years later they had been drinking. In the interview, they stated they had driven what would have been 164 miles (264 km) looking for a place to dispose of Till's body, to the cotton gin to obtain the fan, and back again, which the FBI noted would be impossible in the time they were witnessed having returned. Several witnesses recalled that they saw Bryant, Milam, and two or more black men with Till's beaten body in the back of the pickup truck in Glendora, yet they did not admit to being in Glendora to Huie. (FBI, [2006], pp. 86–96.)

-

Many years later, there were allegations that Till had been castrated. (Mitchell, 2007) John Cothran, the deputy sheriff who was at the scene where Till was removed from the river testified, however, that apart from the decomposition typical of a body being submerged in water, his genitals were intact. (FBI [2006]: Appendix Court transcript, p. 176.) Mamie Till-Mobley also confirmed this in her memoirs. (Till-Bradley and Benson, p. 135.)

-

When Jet publisher John H. Johnson died in 2005, people who remembered his career considered his decision to publish Till's open casket photograph his greatest moment. Michigan congressman Charles Diggs recalled that for the emotion the image stimulated, it was "probably one of the greatest media products in the last 40 or 50 years". (Dewan, 2005)

-

Strider was apparently unable to be consistent with his own theory. Following the trial he told a television reporter that should anyone who had sent him hate mail arrive in Mississippi "the same thing's gonna happen to them that happened to Emmett Till". (Whitfield, p. 44.)

-

The trial transcript reads the line as "There he is", although witnesses recall variations of "Dar he", "Thar he", or "Thar's the one". Wright's family protested that Mose Wright was made to sound illiterate and insists he said "There he is." (Mitchell, 2007)

-

A month after Huie's article appeared in Look, T. R. M. Howard worked with Olive Arnold Adams of The New York Age to put forth a version of the events that agreed more with the testimony at the trial and what Howard had been told by Frank Young. It appeared as a booklet titledTime Bomb: Mississippi Exposed and the Full Story of Emmett Till. Howard also acted as a source for an as-yet unidentified reporter using thepseudonym Amos Dixon in the California Eagle. Dixon wrote a series of articles implicating three black men, and Leslie Milam, who, Dixon asserted, had participated in Till's murder in some way. Time Bomb and Dixon's articles had no lasting impact in the shaping of public opinion. Huie's article in the far more widely circulated Look became the most commonly accepted version of events. (Beito and Beito, pp. 150–151.)

-

Such was the animosity toward the murderers that in 1961, while in Texas, when Bryant recognized the license plate of a Tallahatchie County resident, he called out a greeting and identified himself. The resident, upon hearing the name, drove away without speaking to Bryant. (Whitaker, 2005)

References

-

Houck and Grindy, p. 20.

-

Jr, Deborah Gray White, Mia Bay, Waldo E. Martin (2013).Freedom on my mind : a history of African Americans, with documents. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's. p. 637. ISBN 978-0-312-64884-8.

-

Houck and Grindy, pp. 4–5.

-

Whitfield, p. 15.

-

Beito and Beito, p. 116.

-

Whitaker (1963), p. 19.

-

Till-Mobley and Benson, pp. 14–16.

-

Till-Mobley and Benson, p. 17.

-

Till-Mobley and Benson, pp. 36–38.

-

Till-Mobley and Benson, pp. 56–58.

-

Till-Mobley and Benson, pp. 59–60.

-

Till-Mobley and Benson, pp. 70–87.

-

^ Jump up to:a b c d e

Huie, William Bradford (January 1956). "The Shocking Story of Approved Killing in Mississippi". Look Magazine. Retrieved October 2010.

-

FBI (2006), p. 6.

-

Hampton, p. 2.

-

Till-Mobley and Benson, pp. 98–101.

-

Whitfield, p. 5.

-

Whitaker (1963), pp. 2–10.

-

Whitaker (1963), pp. 61–82.

-

FBI (2006), p. 18.

-

Hampton, p. 3.

-

^ Jump up to:a b c d

FBI (2006), p. 44.

-

Timeline: The Murder of Emmett Till, PBS.org, Accessed January 27, 2014

-

Wright, pp. 50–51.

-

Mettress, p. 20.

-

Whitfield, p. 18.

-

^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i

Whitaker, Stephen (Summer 2005). A Case Study in Southern Justice: The Murder and Trial of Emmett Till,Rhetoric & Public Affairs 8 (2), pp. 189–224.

-

FBI (2006), p. 40.

-

^ Jump up to:a b c d

The Emmett Till Murder Trial: An Account by Douglas Linder, (2012), Accessed January 28, 2014

-

Hampton, pp. 3–4.

-

FBI (2006), p. 46.

-

FBI (2006), pp. 47–49.

-

FBI (2006), pp. 51–56.

-

FBI (2006), pp. 60–66.

-

FBI (2006), pp. 55–57.

-

Hampton, p. 4.

-

Whitfield, p. 21.

-

FBI (2006), p. 68.

-

Hampton, p. 6.

-

FBI (2006), pp. 69–79.

-

Metress, pp. 14–15.

-

FBI (2006), pp. 77–79.

-

Houck and Grindy, p. 6.

-

Houck and Grindy, pp. 19–21.

-

Hampton, p. 5.

-

FBI (2006), pp. 80–81.

-

Beito and Beito, p. 118.

-

Whitfield, pp. 23–26.

-

Metress, pp. 16–20.

-

Houck and Grindy, pp. 22–24.

-

Till-Mobley and Benson, p. 132.

-

Whitfield, p. 23.

-

Houck and Grindy, p. 29.

-

Houck and Grindy, pp. 31–37.

-

Whitfield, pp. 28–30.

-

Whitaker (1963), pp. 21–22.

-

Beito and Beito, p. 119.

-

Whitfield, p. 34.

-

Dewan, Shaila (August 28, 2005). "How Photos Became Icon of Civil Rights Movement", The New York Times. Retrieved October 5, 2010.

-

Beito and Beito, pp. 121–122.

-

Whitfield, p. 38.

-

Beito and Beito, p. 122.

-

Hampton, pp. 10–11.

-

Whitfield, image spread p. 6.

-

Till-Mobley and Benson, image spread p. 12.

-

Hampton, p. 11.

-

Whitfield, p. 39.

-

^ Jump up to:a b c

Mitchell, Jerry (February 19, 2007). "Re-examining Emmett Till case could help separate fact, fiction", USA Today[originally published in theJackson Clarion-Ledger]. Retrieved October 1, 2010.

-

Beito and Beito, pp. 124–126.

-

Whitfield, p. 40.

-

Beito and Beito, p. 126.

-

^ Jump up to:a b c

Beito and Beito, p. 127.

-

Whitfield, pp. 41–42.

-

Rubin, Richard (July 21, 2005). The Ghosts of Emmett Till, New York Times Magazine. Retrieved October 3, 2010.

-

Beito and Beito, p. 128.

-

Whitfield, pp. 48–49.

-

"Willie Louis, Who Named the Killers of Emmett Till at Their Trial, Dies at 76". The New York Times. July 24, 2013.

-

Whitfield, pp. 46–47.

-

Whitfield, p. 117.

-

Houck and Grindy, pp. 134–135.

-

Whitfield, p. 52.

-

Beito and Beito, pp. 150–151.

-

Whitfield, p. 68.

-

Mettress, Christopher (Spring 2003). "Langston Hughes's "Mississippi-1955": A Note on Revisions and an Appeal for Reconsideration" African American Review, 37 (1), pp. 139–148.

-

Whitfield, pp. 83–84.

-

Chura, Patrick (Spring 2000). "Prolepsis and Anachronism: Emmet Till and the Historicity of To Kill a Mockingbird",Southern Literary Journal, 32(2), pp. 1–26.

-

Mettress, Christopher (Spring 2003). "No Justice, No Peace": The Figure of Emmett Till in African American Literature" MELUS, 28 (1), pp. 87–103.

-

Carson, et al, pp. 41–43.

-

Whitfield, pp. 119–120.

-

Hampton, pp. 13–14.

-

"Widow of Emmett Till killer dies quietly, notoriously".USA Today. February 27, 2014.

-

"Widow of Emmett Till killer dies quietly, notoriously".USA Today. February 27, 2014.

-

Atiks, Joe. (August 25, 1985). "Emmett Till: More Than A Murder." The Clarion-Ledger. Reproduced July 2, 2011, at"US Slave" blog. Retrieved July 16, 2013.

-

FBI (2006), pp. 24–26.

-

Till-Mobley and Benson, p. 261.

-

Bradley, Ed (2005). " 60 Minutes Story on Emmett Till Targets Carolyn Bryant".George Mason University's History News Network.

-

Segall, Rebecca; Holmberg, David (February 3, 2003). "Who Killed Emmett Till?" . The Nation 276 (4). pp. 37–40.

-

U.S. Department of Justice (May 10, 2004). "Justice Department to Investigate 1955 Emmett Till Murder".Press release. RetrievedOctober 5, 2010.

-

FBI (2006), pp. 99–109.

-

Associated Press (March 3, 2007). "End of Till case draws mixed response". The Boston Globe. Retrieved October 6, 2010.

-

Whitfield, p. 60.

-

Carson, et al, pp. 39–40.

-

"Interview with Myrlie Evers". Blackside, Inc. November 27, 1985.

-

Till-Mobley and Benson, pp. 191–196.

-

Beito and Beito, p. 130.

-

Houck and Grindy, p. x.

-

Carson, et al, p. 107.

-

Hampton, p. 321.

-

Gorn, p. 76–77.

-

Who, what, why: Who was Emmett Till?, BBC News, 23 July 2013

-

Whitfield, p. 62.

-

Carson, et al, p. 177–178.

-

Trescott, Jacqueline (August 27, 2009). Emmett Till's Casket Donated to the Smithsonian, The Washington Post. Retrieved on October 6, 2010.

-

Civil Rights Memorial, Southern Poverty Law Center. Retrieved on October 12, 2010.

-

Till-Mobley and Benson, pp. 259–260, 268.

-

Lynch, La Risa R. (1 Mar 2006). "South Side School Named for Emmett Till". Chicago Citizen.

-

Houck and Grindy, p. 4.

-

Resolution Presented to Emmett Till’s Family, Emmett Till Memorial Committee Tallahatchie County (October 2, 2007). Retrieved on October 6, 2010.

-

H.R. 923: Emmett Till Unsolved Civil Rights Crime Act of 2007, govtrack.us (2007–2008). Retrieved on September 8, 2009.

-

Authorities discover original casket of Emmett Till,CNN (July 10, 2009). Retrieved on July 10, 2009.

Bibliography

- Beito, David; Beito, Linda (2009). Black Maverick: T. R. M. Howard's Fight for Civil Rights and Economic Power, University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-03420-6

- Carson, Clayborne; Garrow, David; Gill, Gerald; Harding, Vincent; Hine, Darlene Clark (eds.) (1991). Eyes on the Prize: Civil Rights Reader Documents, Speeches, and Firsthand Accounts from the Black Freedom Struggle 1954–1990, Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-015403-0

- Federal Bureau of Investigation (February 9, 2006). Prosecutive Report of Investigation Concerning (Emmett Till) (Flash Video or PDF). Retrieved October 2011.

- Gorn, Elliott (1998). Muhammad Ali: The People's Champ, University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-06721-1

- Hampton, Henry, Fayer, S. (1990). Voices of Freedom: An Oral History of the Civil Rights Movement from the 1950s through the 1980s. Bantam Books. ISBN 978-0-553-05734-8

- Houck, Davis; Grindy, Matthew (2008). Emmett Till and the Mississippi Press, University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-934110-15-7

- Mettress, Christopher (2002). The Lynching of Emmett Till: A Documentary Narrative, The American South series University of Virginia Press. ISBN 978-0-8139-2122-8

- Till-Mobley, Mamie; Benson, Christopher (2003). The Death of Innocence: The Story of the Hate Crime That Changed America, Random House. ISBN 978-1-4000-6117-4

- Whitaker, Hugh Stephen (1963). A Case Study in Southern Justice: The Emmett Till Case, Florida State University (M.A. thesis). Retrieved October 2010.

- Whitfield, Stephen (1991). A Death in the Delta: The story of Emmett Till, JHU Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-4326-6

- Wright, Simeon; Boyd, Herb (2010). Simeon's Story: An Eyewitness Account of the Kidnapping of Emmett Till, Chicago Review Press. ISBN 978-1-55652-783-8

Further reading

- The Murder of Emmett Till. American Experience Transcript and additional materials for PBS film.

- Emmett Till at DMOZ

- The original 1955 Jet magazine with Emmett Till's murder story pp. 6–9, and Emmett Till's Legacy 50 Years Later" in Jet, 2005.

- 1985 documentary, The Murder and the Movement: The Story of the Murder of Emmett Till

- NPR pieces on the Emmett Till murder

- Emmett Till Math & Science Academy (Chicago)

- Keith Beauchamp's The Untold Story of Emmett Louis Till

- Devery S. Anderson, "A Wallet, a White Woman, and a Whistle: Fact and Fiction in Emmett Till's Encounter in Money, Mississippi," Southern Quarterly Summer 2008

- Booknotes interview with Christopher Benson on Death of Innocence: The Story of the Hate Crime That Changed America, April 25, 2004.

Fictionalized accounts of Till and the ensuing events

- Wolf Whistle (1993) by Lewis Nordan

- The Sacred Place (2007) by Daniel Black

- Juvenile fiction: Mississippi Trial, 1955 (2003) by Chris Crowe

- Poem: Emmett Till (1991) by James Emanuel

- Drama: The State of Mississippi and the Face of Emmett Till (2005) by David Barr

- Poem: A Wreath for Emmett Till (2005) by Marilyn Nelson

- Musical: The Ballad of Emmett Till (2008) by Ifa Bayeza

- Drama: Anne and Emmett (2009) by Janet Langhart

- Gathering of Waters (2012) by Bernice L. McFadden

External links

- 1941 births

- 1955 deaths

- 1955 murders in the United States

- African-American history of Mississippi

- Burials in Illinois

- Deaths by beating in the United States

- Deaths by firearm in Mississippi

- History of African-American civil rights

- History of civil rights in the United States

- Murdered African-American people

- Murdered American children

- People from Chicago, Illinois

- People murdered in Mississippi

- Racially motivated violence against African Americans

0 General Document comments

0 Sentence and Paragraph comments

0 Image and Video comments

I’m the Tech Liaison for the New York City Writing Project. I… (more)

I’m the Tech Liaison for the New York City Writing Project. I… (more)

The brutal abduction and murder of 14-year-old African American Emmett Till in Mississippi on August 28, 1955, galvanized the emerging Civil Rights Movement. Martin Luther King, Jr. called his murder “one of the most brutal and inhumane crimes of the 20th century.” – Biography

But what I don’t know is your favorite color, or your favorite bubble gum flavor. I don’t know if you liked winter days, if you ever left the imprint of your body in the snow to make an angel. And I want to know the song that you couldn’t stop listening to, singing it in your head, over and over. What was the song? I want to know the games you liked to play, if you ever climbed a tree, swam in a lake, looked up at the night sky and made a wish. And I want to know who you thought you might become. Your mother told us you were good at science, that you loved art. I wonder if you had lived, would your masterpieces be in a gallery or maybe you would have kept them to yourself—hidden treasures in a notebook, or maybe you would have been an art teacher. Or maybe you would have been a baseball player. I am told you were good at that, too. So many talents, raw and pliable. There is a tale told of you baking a cake for your mother and you were young and boy and not good at baking, but still, you loved your mother, so you tried. The cake did not taste good at all, and that became a family joke. Had you lived, you might have gotten better at baking. And maybe you would have become a renowned pastry chef and every time you’d be interviewed, you’d tell the story of the horrible cake and you’d look back at how far you’d come, at how much you’d grown. Maybe. These are things I do not know. But I do know you were not just a Chicago boy meeting Mississippi, not just a whistling boy, a kidnapped boy, a brutalized boy, a bloated boy with a ring on his finger, not just a boy in an open casket, not just a buried boy, a gone boy. You were a boy with a favorite dessert, a favorite place to play, a favorite joke to tell. You were a boy with a favorite song—a song that you couldn’t stop listening to, couldn’t stop singing it in your head, over and over. What was the song? Had you kept living, maybe you would sing us that song, teaching us the original version. By now the song would be remixed, new verses added, but still the same.

And the record keeps spinning, scratched and stuck on the chorus. So many verses etched in the vinyl. So many unfinished songs.

Your name, the refrain: Emmett Till. Medgar Evers, Martin Luther King, Jr., Henry Dumas, Fred Hampton, Mulugeta Seraw, Amadou Diallo, Sean Bell, Aiyana Jones, Oscar Grant, Trayvon Martin, Jordan Davis, Renisha McBride, Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Michelle Cusseaux, Akai Gurley, Tanisha Anderson, Tamir Rice, Tanisha Fonville, Ezell Ford, Walter Scott, Freddie Gray, Sandra Bland, Alton Sterling, Philando Castile, Stephon Clark, Botham Jean, Aura Rosser, Atatiana Jefferson, Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, Rayshard Brooks

and this is to say, since you were taken away from us, so much has changed and everything is the same. But always, your name is spoken. Like a holy chant, a rally cry, a prayer. We cannot, will not forget you. You are the song stuck in our hearts. And the record keeps spinning, spinning.

RENÉE WATSON is a New York Times bestselling author, educator, and activist. Her young adult novel,

Piecing Me Together (Bloomsbury, 2017) received a Coretta Scott King Award and Newbery Honor. Her

poetry and fiction often centers around the experiences of black girls and women, and explores themes of home, identity, and the intersections of race, class, and gender. Renée served as Founder and Executive Director of I, Too, Arts Collective, a nonprofit committed to nurturing underrepresented voices in the creative arts, from 2016-2019.

Renée grew up in Portland, Oregon, and splits her time between Portland and New York City.

reneewatson.net

New Conversation

Hide Full Comment

New Conversation

New Conversation

New Conversation

New Conversation

New Conversation

General Document Comments 0