Who is Most Affected by the School to Prison Pipeline?

Author: American University

0 General Document comments

0 Sentence and Paragraph comments

0 Image and Video comments

Wednesday, February 24, 2021

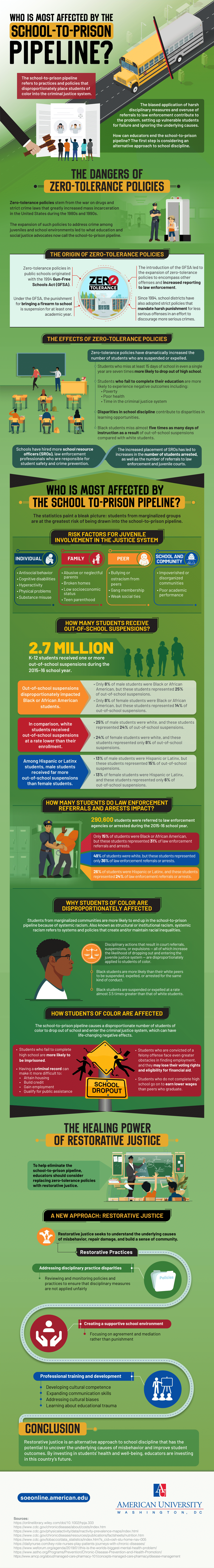

The school-to-prison pipeline refers to practices and policies that disproportionately place students of color into the criminal justice system. The biased application of harsh disciplinary measures and overuse of referrals to law enforcement contribute to the problem, setting up vulnerable students for failure and ignoring the underlying causes.

How can educators end the school-to-prison pipeline? The first step is considering an alternative approach to school discipline.

To learn more, check out the infographic created by American University’s Doctorate in Education Policy & Leadership program.

The Dangers of Zero-Tolerance Policies

Zero-tolerance policies stem from the war on drugs and strict crime laws that greatly increased mass incarceration in the United States during the 1980s and 1990s. The expansion of such policies to address crime among juveniles and school environments led to what education and social justice advocates now call the school-to-prison pipeline.

The Origin of Zero-Tolerance Policies

Zero-tolerance policies in public schools originated with the 1994 Gun-Free Schools Act (GFSA). Under this act, the punishment for bringing a firearm to school is suspension for at least one academic year. The GFSA’s introduction led to the expansion of zero-tolerance policies to concoimpass other offenses and increased reporting to law enforcement. Since 1994, school districts have also adopted strict policies that mandate harsh punishment for less serious offenses in an effort to discourage more serious crimes.

The Effects of Zero-Tolerance Policies

Zero-tolerance policies have dramatically increased the number of students who are suspended or expelled. This has led to serious ramifications. For example, students who miss at least 15 days of school in even a single year are seven times more likely to drop out of high school. Students who fail to complete their education are more likely to experience negative outcomes such as poverty, poor health, or time in the criminal justice system. Furthermore, it’s been determined that disparities in school discipline contribute to disparities in the learning opportunities. It’s also been determined that Black students miss almost five times as many days of instruction as a result of out-of-school suspensions compared with white students.

Along the way, schools have hired more school resource officers (SROs), law enforcement professionals who are responsible for student safety and crime prevention. The increased placement of SROs has led to increases in the number of students arrested, as well as the number of referrals to law enforcement and juvenile courts.

Who Is Most Affected by The School-to-Prison Pipeline?

The statistics paint a bleak picture: students from marginalized groups are the greatest risk of being drawn into the school-to-prison pipeline.

Risk Factors for Juvenile Involvement in the Justice System

There are different risk factor tiers concerning juvenile involvement in the justice system. Individual risk factors include antisocial behavior, hyperactivity, and substance misuse. Family risk factors include abusive parents, low socioeconomic status, and teen parenthood. Peer risk factors include bullying from peers, gang membership, and weak social ties. School and community factors include impoverished or disorganized communities and poor academic performance.

How Many Students Receive Out-of-School Suspensions?

2.7 million K-12 students received one or more out-of-school suspensions during the 2015-16 school year. This number revealed a disproportionate impact on Black or African American students. While this demographic made up just 8% of both the male and female students, they represented 25% and 14% of their respective gender’s out-of-school suspensions.

In comparison, white students received out-of-school suspensions at a rate lower than their enrollment. While 25% of the male student population and 24% of the female student population were white, they only represented 24% and 8% of out-of-school suspensions, respectively.

Among Hispanic or Latinx students, male students received far more out-of-school suspension than female students. Hispanc and Latinx males and females both made up 13% of the student population, but they represented 15% and 6% of out-of-school suspensions, respectively.

How Many Students Do Law Enforcement Referrals and Arrests Impact?

290,600 students were referred to law enforcement agencies or arrested during the 2015-16 school year. Only 15% of students were Black or African American, but these students represented 31% of law enforcement referrals and arrests. 49% of students were white, but these students represented just 36% of law enforcement referrals or arrests. 26% of students were Hispanic or Latinx, and these students represented 24% of law enforcement referrals or arrests.

Why Students of Color are Disproportionately Affected

Students from marginalized communities are more likely to end up in the school-to-prison pipeline because of systemic racism. Also known as structural or institutional racism, systemic racism refers to systems and policies that create and/or maintain racial inequalities.

Disciplinary actions that result in court referrals, suspensions, or expulsions - all of which increase the likelihood of dropping out and entering the juvenile justice system - are disproportionately applied to students of color. Additionally, Black students are more likely than their white peers to be suspended, expelled, or arrested for the same kind of conduct. Furthermore, Black students are suspended or expelled at a rate almost 3.5 times greater than that of white students.

How Students of Color Are Affected

The school-to-prison pipeline causes a disproportionate number of students of color to drop out of school and enter the criminal justice system, which can have life-changing negative effects.

For instance, students who fail to complete high school are more likely to be imprisoned. This gives them a criminal record, which can then make it more difficult to attain housing, build credit, gain employment, and qualify for public assistance. Additionally, students who are convicted of a felony offense face even greater obstacles in finding employment, and they may lose their voting rights and eligibility for financial aid. Students who do not complete high school also go on to earn lower wages compared to peers that graduate.

The Healing Power of Restorative Justice

To help eliminate the school-to-prison pipeline, educators should consider replacing zero-tolerance policies with restorative justice.

A New Approach: Restorative Justice

Restorative justice seeks to understand the underlying causes of misbehavior, repair damage, and build a sense of community. This process breaks down into several restorative practices. The first practice is to address the disciplinary practice disparities by reviewing and monitoring policies and practices to ensure that disciplinary measures are not applied unfairly. The second practice is to create a supportive school environment that focuses on agreement and mediation instead of punishment. The third practice is to utilize professional training and development to develop cultural competence, expand communication skills, address cultural bias, and learn about educational trauma.

A Better Approach

Restorative justice is an alternative approach to school discipline that has the potential to uncover the underlying causes of misbehavior and improve student outcomes. By investing in students’ health and well-being, educators are investing in this country’s future.

General Document Comments 0

0 archived comments