Can we feed 10 billion people on organic farming alone?

Organic farming creates more profit and yields healthier produce. It’s time it played the role it deserves in feeding a rapidly growing world population

In 1971, then US Secretary of Agriculture Earl Butz uttered these unsympathetic words: “Before we go back to organic agriculture in this country, somebody must decide which 50 million Americans we are going to let starve or go hungry.” Since then, critics have continued to argue that organic agriculture is inefficient, requiring more land than conventional agriculture to yield the same amount of food. Proponents have countered that increasing research could reduce the yield gap, and organic agriculture generates environmental, health and socioeconomic benefits that can’t be found with conventional farming.

Organic agriculture occupies only 1% of global agricultural land, making it a relatively untapped resource for one of the greatest challenges facing humanity: producing enough food for a population that could reach 10 billion by 2050, without the extensive deforestation and harm to the wider environment.

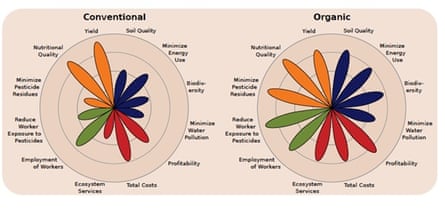

That’s the conclusion my doctoral student Jonathan Wachter and I reached in reviewing 40 years of science and hundreds of scientific studies comparing the long term prospects of organic and conventional farming. The study, Organic Agriculture in the 21st Century, published in Nature Plants, is the first to compare organic and conventional agriculture across the four main metrics of sustainability identified by the US National Academy of Sciences: be productive, economically profitable, environmentally sound and socially just. Like a chair, for a farm to be sustainable, it needs to be stable, with all four legs being managed so they are in balance.

We found that although organic farming systems produce yields that average 10-20% less than conventional agriculture, they are more profitable and environmentally friendly. Historically, conventional agriculture has focused on increasing yields at the expense of the other three sustainability metrics.

In addition, organic farming delivers equally or more nutritious foods that contain less or no pesticide residues, and provide greater social benefits than their conventional counterparts.

With organic agriculture, environmental costs tend to be lower and the benefits greater. Biodiversity loss, environmental degradation and severe impacts on ecosystem services – which refer to nature’s support of wildlife habitat, crop pollination, soil health and other benefits – have not only accompanied conventional farming systems, but have often extended well beyond the boundaries of their fields, such as fertilizer runoff into rivers.

Overall, organic farms tend to have better soil quality and reduce soil erosion compared to their conventional counterparts. Organic agriculture generally creates less soil and water pollution and lower greenhouse gas emissions, and is more energy efficient. Organic agriculture is also associated with greater biodiversity of plants, animals, insects and microbes as well as genetic diversity.

Despite lower yields, organic agriculture is more profitable (by 22–35%) for farmers because consumers are willing to pay more. These higher prices essentially compensate farmers for preserving the quality of their land.

Studies that evaluate social equity and quality of life for farm communities are few. Still, organic farming has been shown to create more jobs and reduce farm workers’ exposure to pesticides and other chemicals.

Organic farming can help to both feed the world and preserve wildland. In a study published this year, researchers modeled 500 food production scenarios to see if we can feed an estimated world population of 9.6 billion people in 2050 without expanding the area of farmland we already use. They found that enough food could be produced with lower-yielding organic farming, if people become vegetarians or eat a more plant-based diet with lower meat consumption. The existing farmland can feed that many people if they are all vegan, a 94% success rate if they are vegetarian, 39% with a completely organic diet, and 15% with the Western-style diet based on meat.

Realistically, we can’t expect everyone to forgo meat. Organic isn’t the only sustainable option to conventional farming either. Other viable types of farming exist, such as integrated farming where you blend organic with conventional practices or grass-fed livestock systems.

More than 40 years after Earl Butz’s comment, we are in a new era of agriculture.During this period, the number of organic farms, the extent of organically farmed land, the amount of research funding devoted to organic farming and the market size for organic foods have steadily increased. Sales of organic foods and beverages are rapidly growing in the world, increasing almost fivefold between 1999 and 2013 to $72bn. This 2013 figure is projected to double by 2018. Closer to home, organic food and beverage sales in 2015 represented almost 5% of US food and beverage sales, up from 0.8% in 1997.

Scaling up organic agriculture with appropriate public policies and private investment is an important step for global food and ecosystem security. The challenge facing policymakers is to develop government policies that support conventional farmers converting to organic systems. For the private business sector, investing in organics offers a lot of entrepreneurial opportunities and is an area of budding growth that will likely continue for years to come.

In a time of increasing population growth, climate change and environmental degradation, we need agricultural systems that come with a more balanced portfolio of sustainability benefits. Organic farming is one of the healthiest and strongest sectors in agriculture today and will continue to grow and play a larger part in feeding the world. It produces adequate yields and better unites human health, environment and socioeconomic objectives than conventional farming.

John Reganold is a Regents Professor of Soil Science & Agroecology at the Washington State University.

0 archived comments