20th Anniversary of Largest Chemical Spill in California History

https://dtsc.ca.gov/20th-anniversary-of-largest-chemical-spill-in-california-history/#:~:text=July%2014%2C%201991,the%20Sacramento%20River%20near%20Dunsmuir.

Cantara Loop Spill Timeline

July 14, 1991

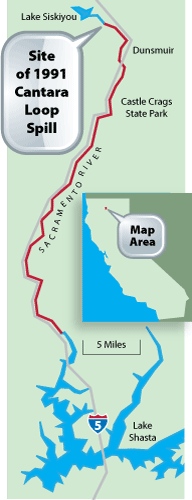

A Southern Pacific Railroad tank car spills 19,000 gallons of the soil fumigant metam sodium into the Sacramento River near Dunsmuir.

July 17

The contaminant flows 41 miles to Shasta Lake, eventually killing more than a million fish and hundreds of thousands of trees.

July 29

Aeration in Lake Shasta dilutes the spill to undetectable levels.

1992

The State of California and U.S. Government file suit against the railroad seeking financial damages.

1994

State officials reopen the Sacramento River for trout fishing.

1995

Parties to the lawsuit again Southern Pacific announce a $38 million settlement.

2005

Biological studies confirm that the river’s rainbow trout population have fully recovered from the spill.

Source: Cantara Trustee Council: Final Report on the Recovery of the Upper Sacramento River, 2007.

Kristi Osborn still remembers the confusion that Monday morning in July 1991.

In the Siskiyou County town of Dunsmuir, people felt sick and disoriented, their nerves rattled by conflicting information.

Outside town, a massive vaporous chemical spill was killing all life in the Sacramento River. A chaotic, uncoordinated influx of government agencies barking orders added to the commotion. Despite good intentions, public agencies clearly weren’t prepared to manage an event of such magnitude and scientific complexities.

“People said keep your windows shut.

Don’t let that stuff in your house.

Or don’t go outside.

You might drag it in,” says Osborn, then a heavy equipment operator with a two-year-old daughter.

Others, she recalls, said to keep the windows open and get that stuff out of the house.

“People said keep your windows shut.

Don’t let that stuff in your house.

Or don’t go outside.

You might drag it in,” says Osborn, then a heavy equipment operator with a two-year-old daughter.

Others, she recalls, said to keep the windows open and get that stuff out of the house.

“It was crazy, not knowing what to do,” she says.

This month the 1991 Cantara chemical spill marks its 20th anniversary. The accident still ranks as the largest hazardous chemical spill in California history. In the darkness of a Sunday night, July 14, a Southern Pacific Railroad train rounding the Cantara Loop over one of the Sacramento River’s most pristine stretches jumped the track. A tanker carrying 19,000 gallons of the deadly soil sterilizer, metam sodium, toppled into the water below, a gash in its side. The surreal green chemical gushed into one of America’s most renowned trout-fishing rivers.

The spill, accompanied by a toxic chemical cloud that sent area residents to hospitals, quickly stripped bare a 41-mile stretch of the Sacramento River. Wildlife experts estimate the agricultural fumigant designed to kill soil pests killed more than one million fish and thousands of trees during a three-day floating journey to Shasta Lake.

“The rocks were clean. There was no moss. There was no life in the river,” says Osborn, now a Bay Area resident. Then, she led Concerned Citizens of Dunsmuir and testified before Congress about local health effects.

Eventually, Southern Pacific paid $38 million for damages, cleanup and river restoration. Spurred by the disaster, the California Legislature and Governor Pete Wilson agreed something needed to be done and authorized the Department of Toxic Substances Control (DTSC) to create the Railroad Accident Prevention and Immediate Deployment (RAPID) program.

And in a noteworthy coincidence, the California Environmental Protection Agency was established three days after the spill occurred. Cal/EPA’s founding, which aimed to provide a unified command for environmental regulation and emergencies like Cantara, included creation of DTSC to address and limit damage of chemical contaminants.

Karl Palmer, one-time head of RAPID’s emergency response branch and now a Branch Chief in DTSC’s Safer Consumer Products program, recalls Cantara as “a real eye opener. It showed how one tank car in one river can be a catastrophe. And it showed that railroads and trucks are a huge conduit for chemical transportation.”

Cantara’s 20th anniversary marks notable changes. The Sacramento River has proved resilient with the return of trout and tourism. Says Osborn: “The Upper Sacramento is as beautiful as ever.” Bob Grace, owner of Dunsmuir’s Ted Fay Fly Shop, adds, “One of the important lessons in this is the regenerative power of nature.”

As Cal/EPA and DTSC celebrate their own anniversaries, Californians can rest assured that systems designed to avoid another Cantara-scale disaster are in place. DTSC’s Emergency Response Program has gone on to provide support, training and technical expertise to many emergency incidents involving toxic chemicals, and the state considers itself more prepared for such disasters than 20 years ago, though industry funding for RAPID is discontinued.

Nonetheless, trains and trucks carrying chemicals continue to roll daily through California’s environment – just as on a fateful Sunday night in July 1991. Cantara remains a vivid warning, an enduring reminder of chemical risk.

0 General Document comments

0 Sentence and Paragraph comments

0 Image and Video comments

New Conversation

New Conversation

New Conversation

General Document Comments 0