Stolen Generations

1 additions to document , most recent over 7 years ago

| When | Why |

|---|---|

| Nov-21-17 | didn't know up the first time |

0 General Document comments

0 Sentence and Paragraph comments

0 Image and Video comments

One of the darkest chapters of Australian history was the forced removal of Aboriginal children from their families. Children as young as babies were stolen from their families to be placed in girls and boys homes, foster families or missions. At the age of 18 they were ‘released’ into white society, most scarred for life by their experiences.

These Aboriginal people are collectively referred to as the ‘Stolen Generations’ because several generations were affected.

Many Aboriginal people are still searching for their parents and siblings.

Watch this 8-minute video from Australian Screen that summarised the key points of the Stolen Generations:

I feel our childhood has been taken away from us and it has left a big hole in our lives.—Jennifer, personal story in the Bringing Them Home Report

A guide to the Stolen Generations

Define ‘Stolen Generations’

The term “Stolen Generations” is used for Aboriginal people forcefully taken away (stolen) from their families between the 1890s and 1970s, many to never to see their parents, siblings or relatives again. Because the period covers many decades we speak of “generations” (plural) rather than “generation”.

Why were Aboriginal children stolen?

This was happening for almost 90 years.

This is the most burning question for members of the Stolen Generations. In removing their children white people stole Aboriginal people’s future. Language, tradition, knowledge, dances and spirituality could only live if passed on to their children. In breaking this circle of life white people hoped to end Aboriginal culture within a short time and get rid of “the Aboriginal problem”.

In the early 20th century under the assimilation policy white Australians thought Aboriginal people would die out. In three generations, they thought, Aboriginal genes would have been ‘bred out’ when Aboriginal people had children with white people.

“It was a presumption for many years that we girls would grow up and marry nice white boys,” says Aboriginal woman Barbara Cummings, a member of the Stolen Generations [31]. “We would have nice fairer children who, if they were girls, would marry white boys again and eventually the colour would die out. That was the original plan - the whole removal policy was based on the women because the women could breed.”

Adult Aboriginal people resisted efforts to be driven out of towns by simply coming back. But children taken away were much easier to control.

I grew up feeling alone, a black girl in a white world, and I resented them for trying to make me white but they couldn't wash away thousands of years of dreaming.—Aunty Rhonda Collard, member of the Stolen Generations [10]

Aboriginal children who were taken away also fed the insatiable demand for station workers and domestic servants. Without these cheap, and often unpaid, labourers white Australians wouldn’t have been able to build the wealth and infrastructure that helped them prosper. This is where the Stolen Generations and the stolen wages become one story.

Authorities also took children away pretending that Aboriginal parents would neglect them. There is evidence, however, that kids were malnourished or starving because Aboriginal people were not paid the full wages they were owed [7].

Reasons why Aboriginal girls were taken away (in %).

These statistics list the ‘reasons’ for forcibly removing Aboriginal girls from their families.

“Other” reasons include “being female on an Aboriginal reserve” and simply because of being “Aboriginal”.

[15]

Reasons why Aboriginal girls were taken away (in %).

These statistics list the ‘reasons’ for forcibly removing Aboriginal girls from their families.

“Other” reasons include “being female on an Aboriginal reserve” and simply because of being “Aboriginal”.

[15]

Which children were taken away?

Authorities targeted mainly children of mixed descent, i.e. what they called ‘half-caste’ Aboriginal children (caution, this is a derogatory term!) . It was thought these Aboriginal children could be assimilated more easily into white society.

iam shocked by this because innocent children disappear

During this time many children were not told that they were Aboriginal and discovered this much later in their lives. So-called ‘A grade’ babies were not obviously Aboriginal and were fostered out without telling their new parents their heritage. For ‘B grade’ babies, one could tell their Aboriginal heritage if knowing “what to look out for”.

What happened to the stolen children?

every bed to see those kid have to go with

Often babies were stolen at birth, and their mother given no chance of seeing them for the first time. They were called ‘Blanket Babies’ because nurses covered them with a blanket to hide them from their mothers. [46]

The stolen children were raised on missions or by foster parents, totally cut off from their Aboriginality. They were severely punished when caught talking their Aboriginal language. Some children never learned anything traditional and received little or no education. Instead the girls were trained to be domestic servants, the boys to be stockmen.

Many of the stolen girls and boys were physically, emotionally and sexually abused. Many babies born to girls raped by white men were also taken away from them, sometimes as soon as they were born.

There is no black or white, we are both of those. I am black and I am white. We were the product of white men raping our traditional women. We were an embarrassment. No-one wanted us. They just wanted us out of the way.—Zita Wallace, taken aged eight years [8]

Paragraph 26 0

No paragraph-level conversations. Start one.

No paragraph-level conversations. Start one.

Boys and girls were brought into separate institutions which they (and some experts) would later compare with German concentration camps and the holocaust. Many tried to run away but few succeeded. Many never saw their parents again or were told they were orphans.

We were each handed a pair of pyjamas with a number Mr Borland, the manager, had given us earlier printed on the pocket, and a shirt and pair of shorts also. I was number 33. Not Bill. Not even Simon. Just number 33.—Bill Simon, taken away aged 10 [14]

Institutions in NSW where stolen Aboriginal children were more or less imprisoned to be trained as domestics or labourers.

Institutions in NSW where stolen Aboriginal children were more or less imprisoned to be trained as domestics or labourers.

Many of those who were stolen established links with the area where they stayed for many years. After they left the institutions these people settled in the area.

However, the women and men also passed on the kinds of abuse they suffered to their own children (intergenerational trauma).

Sometimes at night we'd cry with hunger. We had to scrounge in the town dump, eating old bread, smashing tomato sauce bottles, licking them.—Bringing Them Home - Community Guide, children's experiences

The effects on the stolen children and their families were profound and are ongoing.

Aboriginal people suffer from many social and personal problems including mental illness, violence, alcoholism and welfare dependance

How many children were stolen?

That is not easy to answer. Few records of stolen children were kept, some were deliberately destroyed or just lost. Some administrations tried to tout their “successful assimilation” of Aboriginal people by deliberately understating Aboriginal numbers, thus distorting data.

Hence numbers can only be roughly estimated. It is estimated that between 1883 and 1969 more than 6,200 children were stolen in NSW alone.

A 1994 survey by the Australian Bureau of Statistics stated that one in every ten (10%) Aboriginal people aged over 25 had been removed from their families in childhood, a figure which seems to be confirmed by research since the Bringing Them Home Report. Australia-wide numbers are in the tens of thousands.

If you apply this proportion to the 2011 Census figures of the Aboriginal population you’ll get around 14,700 Stolen Generations members for that year. Considering those with immediate family who had been removed, an additional 160,000 Aboriginal people are directly affected by the policies of the Stolen Generations. [52]

The [South Australian] government was unable to say how many Stolen Generation people live in the state.—Statement in a 2007 article about the first court-ordered compensation ruling [5

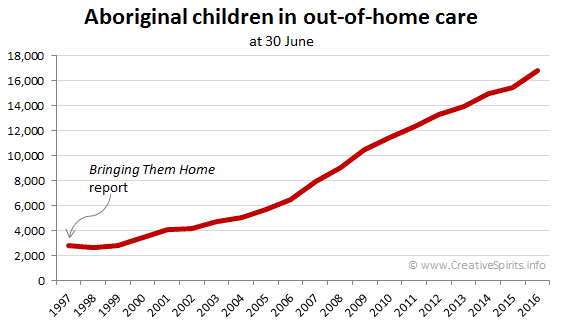

More and more Aboriginal children are stolen from their families even today. In 2016, 6 times as many children were in out-of-home care than when the Bringing Them Home report was published. [49]

Children continue to be taken from their families. The Department of Community Services (DoCS) has the authority to remove children from their families if they were “at risk of significant harm”.

If you don't already know, the Stolen Generation scenario still applies today and has been here for a long time and will continue to be here.—Paul Ralph, CEO of KARI Aboriginal Resources Inc [28]

About 60 children are being taken away every month by child protection services, says Elder Djiniyini Gondarra, who represents 8,000 Yolngu people of east Arnhem Land [29]. “Children are being taken away from us at numbers not seen since the Stolen Generations.”

Indeed, since the National Apology to the Stolen Generations in 2008 the number of Aboriginal children in care has increased by 65%.

Why are they still taken away?

Intergenerational effects of separation from family and culture are partly to blame: parents stolen as kids are passing on this trauma to their own children.

But many government workers who decide about removing children seem to have difficulty telling neglect from poverty.

Larrakia elder Dr Christine Fejo-King was a consultant to the NT Royal Commission into the Protection and Detention of Children in the Northern Territory. She found neglect was the biggest reason why Aboriginal children were removed from their families, but the system was confusing the effects of absolute poverty with the concept of neglect. [53]

“There’s a difference between absolute poverty which is often then equated to neglect as opposed to actual life-threatening situations for that child as a result of the people that they’re living with in an unsafe place,” she said.

Aboriginal children are mostly removed for ‘neglect’ or ‘emotional abuse’. I have seen first hand how these judgements are made on a racist basis, or arise directly from the extreme poverty faced by families.—Padraic Gibson, Senior Researcher, Jumbunna Indigenous House of Learning, University of Technology, Sydney [43]

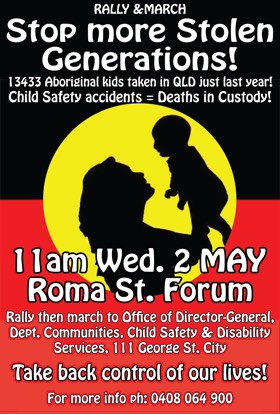

Call to protest against the taking of more children. On 2 May 2012 Aboriginal people rallied and marched on the Department of Child Safety in Brisbane. They also protested against children dying while in 'care'. [42]

Was it legal to steal Aboriginal children?

With all the pain and trauma caused by the child removal policies one has to ask: Was this legal? Didn’t these laws violate basic human rights?

These questions were put to Australia’s High Court in 1997 when two members of the Stolen Generations sued the Commonwealth (Kruger vs Commonwealth). They argued that the laws breached basic fundamental human rights such as the right to due process before the law, equality before the law, freedom of movement and freedom of religion.

In a “dramatic demonstration of Australia’s lack of rights protection” [27] the High Court held that none of these rights were protected. We are not talking Aboriginal rights here—we are talking human rights!

In other words, it was perfectly legal for Australia’s government to forcibly remove Aboriginal children.

Australia’s failure to protect basic human rights falls hardest on the poor, the marginalised and the socioeconomic disadvantaged. That is, they fall hardest on Aboriginal people, families and communities.—Prof. Larissa Behrendt, Aboriginal barrister [6

Healing members of the Stolen Generations

The hibiscus flower is a symbol for the Stolen Generations.

It was chosen because its lilac colour denotes spiritual healing and compassion and for the fact that it is widespread, grows everywhere and is a survivor [30].

Photo: butupa, Flickr

The hibiscus flower is a symbol for the Stolen Generations.

It was chosen because its lilac colour denotes spiritual healing and compassion and for the fact that it is widespread, grows everywhere and is a survivor [30].

Photo: butupa, Flickr

On 13 February 2009, one year after it apologised to the Stolen Generations, the Australian government promised to establish the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Healing Foundation.

The foundation is designed to deal with the “trauma experienced by all Aboriginal people as the after-effect of colonisation” [13], but with a particular focus on the Stolen Generations.

It won’t deliver healing services, instead it funds healing work, educates communities and social workers and evaluates healing programs to find out what works.

According to Aboriginal trauma and grief specialist Dr Greg Phillips, healing is “a spiritual process that includes recovery from addiction, therapeutic change and cultural renewal” [13].

Healing is not just another government program. It has taken many generations to get to this level of trauma and it will take quite a few to fully recover from it.—Dr Greg Phillips, Aboriginal trauma and grief specialist from the Waanyi people [13]

Many members of the Stolen Generations attend annual reunions where they meet fellow Aboriginal people to share their stories and experiences they endured as children in the institutions where they were raised. The Link-Up service (see bottom of this page) often supplies funding for these reunions. For many this is the start of their journey of healing.

Denying history: ‘Not stolen, but rescued’

A significant number of Australians disagreed with the apology delivered in February 2008 to the Stolen Generations by Prime Minister Kevin Rudd. Here are their main arguments:

In my option the stolen are bad because that like divided the family and make the family sad.

- The Stolen Generations don’t exist. Some people simply and flatly deny that children were stolen. They want to see ‘proof’ and claim no-one could ‘find’ them. For example, journalist Andrew Bolt claimed the Stolen Generations were “a giant intellectual fraud with unforgivable consequences” and “no one has yet produced a single child who was stolen under a government policy to remove children just because they were Aboriginal and not because they needed help.” [45]

-

Aboriginal children were ‘rescued’.

Supporters claim that Aboriginal children were not stolen but ‘rescued’ from a family and community environment that was “rife with rape, incest, drug and/or alcohol abuse and insanitary living conditions” [9].

The Aboriginal children were ‘given a chance’.

I've asked my granny if she thought she was rescued. She replied, "I didn't need rescuing from my mother's love."—Che Cockatoo-Collins [16]

- ‘We did not do it’. People who refuse to apologise to the Stolen Generations feel that they or their ancestors had no part in what happened, hence shared no responsibility for the pain caused.

- An apology leads to compensation claims. Many people fear that after the apology “a flood of compensation claims will be forthcoming” running to “millions of dollars” [9].

Source: https://www.creativespirits.info/aboriginalculture/politics/a-guide-to-australias-stolen-generations#ixzz4z5hqOWB6

Added November 21, 2017 at 1:45pm

by louise bauso

Title: didn't know up the first time

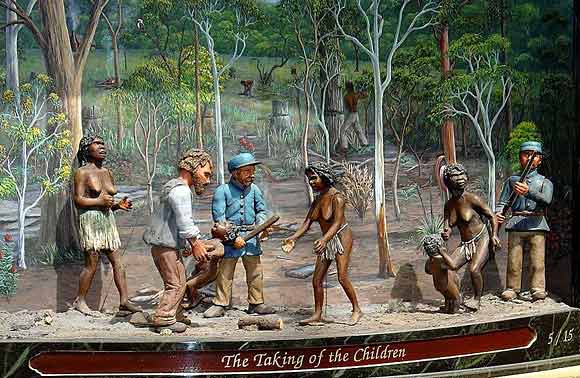

Detail of the ‘Great Australian Clock’, Queen Victoria Building, Sydney.

Note that the artist confined Aboriginal men to the painted background, seemingly ignorant of the situation.

You can view the clock from the highest level inside the building.

Detail of the ‘Great Australian Clock’, Queen Victoria Building, Sydney.

Note that the artist confined Aboriginal men to the painted background, seemingly ignorant of the situation.

You can view the clock from the highest level inside the building.

Tip:

Watch this 8-minute video from Australian Screen that summarised the key points of the Stolen Generations:

General Document Comments 0

0 archived comments