Making Up Is Hard to Do

Author: Conor Friendersdorf

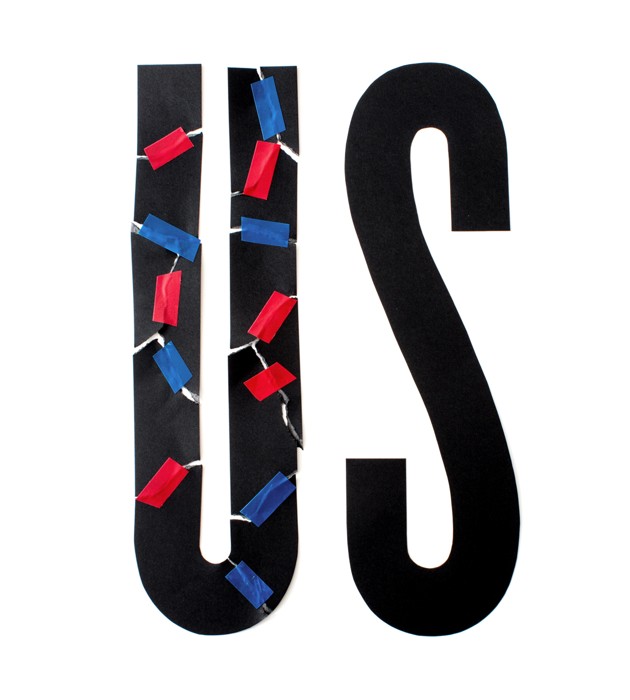

Are you ever nostalgic for the bygone days when the cable networks sorted Americans neatly into a red team and a blue team, and we fought over the patriot Act, the Iraq War, and gay marriage? There was a lot to lament. Many people felt anxious about how divided the country seemed. But then a charismatic young man with a white mother and a black father tried to comfort us. “The pundits like to slice and dice our country into … red states for Republicans, blue states for Democrats,” he said. “But I’ve got news for them … We worship an awesome God in the blue states, and we don’t like federal agents poking around in our libraries in the red states. We coach Little League in the blue states and, yes, we’ve got gay friends in the red states … We are one people.”

Back in 2004, we didn’t know whether Barack Obama was right, but no matter. “Try to see it my way,” the Beatles counseled. “Only time will tell if I am right or I am wrong. While you see it your way, there’s a chance that we might fall apart before too long.” So we made him a senator, and then the president.

There was still a lot to lament.

But his successor will be someone Americans like less: This year, both major presidential candidates surpass all predecessors in the dislike they engender.

So I’m nostalgic for the days when the country appeared united, or at the very least united in halves. Today, people who recently seemed as though they were on the same team are at odds. (Even Jay Z and Beyoncé seem shaky!)

In politics, the GOP coalition that married on Fox News in 2000, honeymooned in Baghdad, and separated during the Tea Party was, by the time it convened in Cleveland in July, divorcing. Many social gatherings got awkward. Was it weird to invite pro-Trumpers and Never Trumpers?

Then Hillary Clinton went to Philadelphia to accept the Democratic nomination. Some Bernie Sanders supporters declared that the primaries had been rigged. One crowd in a public square cheered a speaker who vowed that there would be “a massive de-registration” from the Democratic Party. Another crowd with bernie or bust signs chanted “Revolution!”

On campus, kids of the same generation, who chose to enroll at the same colleges, having been selected by the same admissions officers, based largely on their similar cognitive profiles, spent the last school year feuding about the inclusiveness of their communities and how to regulate one another’s speech. We have witnessed Occupy Wall Street protests that vilified “the 1 percent.” The treatment of cops who have killed young black men has divided dozens of municipalities: Ferguson, Baltimore, and Milwaukee have erupted into riots. On the far right, dozens flocked to Ammon Bundy during his armed standoff with law enforcement in Oregon.

Confronted with a Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, a Dylann Roof, or an Omar Mateen, Americans remain united: At minimum, the penalty for lethal terrorism or mass murder should be permanent removal from the community, regardless of the perpetrator’s allegiances.

But many people now seem inclined to favor banishment for ideological infractions, too. A common theme is fight or flight. Campaign events come to blows. An anti-Hillary faction has taken to chanting “Lock her up!” during Trump rallies. Some anti-Trump voters swear that, this time, they really will move abroad if he is elected (for more on this phenomenon, see “How Voters Respond to Electoral Defeat”). Some college students believe the penalty for hate speech ought to be expulsion; others say they need “safe spaces.” Libertarians have debated the wisdom of floating ocean platforms that are states unto themselves. On the secular left, many believe a Christian bakery that declines to bake a cake for a gay wedding or a Catholic hospital that doesn’t perform abortions should be compelled to do so. Rod Dreher, a thoughtful religious traditionalist, is leading a group of thinkers who believe the only way forward is withdrawal into enclaves apart from secular culture.

Perhaps a lucky few Americans really can flee into what they regard as utopias. But for most, the impulse to withdraw, or to force the withdrawal of others, is rooted in a reluctance to face this reality: No matter who wins the election, or the next skirmish in the culture wars, most Americans must live together, and will live together, within these borders, with people whose actions or views are anathema to them.

How, then, canwe get along? Many believe the country would be at peace if only we better educated our children. On the right, one ideal is for more kids to learn from both a mother and a father; attend Sunday school; study civics; and, in college, glean wisdom from the Great Books. Aristotle! Plutarch! Montesquieu! What could be a better foundation for good citizenship? Progressives, for their part, might propose a Montessori education, a gay-straight alliance at a diverse high school, college classes that teach “cultural competency,” time abroad, and a workplace where new hires go through sexual-harassment training.

In either case, trying to teach our way out of this problem could doom us to failure.

Karen Stenner, a political psychologist, has spent significant time studying the people who express an outsize share of political, racial, and moral intolerance. The threat this cohort poses to liberal democracies springs not from flawed or inadequate socialization, she argues, but from a largely immutable characteristic: They are inclined to want oneness and sameness. As long as they perceive their country to be sufficiently unified and in consensus, that need is met, and they are relatively tolerant.

But when their need for unity is threatened, as is inevitable in liberal democracies, they lash out. They may demand racial discrimination, restrictions on immigration, limits on free speech, stricter policies on homosexuality, and harsher punishments for criminals.

Stenner says that these people have a psychological predisposition to “authoritarianism”—and whole countries suffer when it is activated. This is not, to be clear, a political designation. Nor is it akin to conservatism, false stereotypes to the contrary.

Regrettably, nothing is more certain to trigger authoritarianism “than the likes of ‘multicultural education,’ bilingual policies, and nonassimilation,” Stenner writes. “Our showy celebration of, and absolute insistence upon, individual autonomy and unconstrained diversity pushes those by nature least equipped to live comfortably in a liberal democracy not to the limits of their tolerance, but to their intolerant extremes.” By contrast, she notes, “nothing inspires greater tolerance from the intolerant than an abundance of common and unifying beliefs, practices, rituals, institutions, and processes.”

Jonathan Haidt, a social psychologist and the author of The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion, believes that Stenner’s theory helps explain Donald Trump’s embrace of authoritarian logic and rhetoric.

When the Democrats adopted “We are stronger together” as a convention slogan, Haidt observes, it was almost as if they were heeding the advice of scholars like Stenner to suppress intolerance by celebrating sameness.

In Haidt’s telling, the convention’s most successful moment was when Khizr Khan stood onstage with his wife, brandishing a pocket Constitution and declaring, “We are honored to stand here as the parents of Captain Humayun Khan, and as patriotic American Muslims with undivided loyalty to our country.”

If progressives balk at this prescription—if they resent the idea of parading sameness or of dialing down the type of multiculturalist rhetoric that’s been shown to provoke the intolerant—they might reflect on Stenner’s warning: Given that immutable attributes constrain a person’s ability to deal with differences, “well-meaning programs celebrating multiculturalism … might aggravate more than educate, might intensify rather than diminish, intolerance.”

Progressives may find comfort in the fact that ideological conservatives wishing to fight balkanization must swallow an equally bitter pill. According to Stenner, another thing that triggers intolerance is the perception—promoted by many on the right since 2008—that a polity’s leaders are failing and untrustworthy.

Most conservatives will rightly decline to cease all criticism of politicians.

But they could, while still holding officials accountable, cut out lies and wild hyperbole.

Our ability to live together as a country is harmed when prominent intellectuals on the right assert, as Andrew C. McCarthy did in his book The Grand Jihad, that President Obama is allied with America’s Islamist enemy, or, as Dinesh D’Souza has, that Obama’s approach is best explained by African anticolonial ideology—just as it was harmed by those who compared George W. Bush to Adolf Hitler or insisted that his administration plotted the attacks of 9/11.

The incentives to spread polarizing allegations would shrink if the right reversed one of its biggest strategic errors: retreating from shared institutions, especially in academia and the mainstream media, to create shadow alternatives. The high-water mark of the Reagan Revolution preceded the rise of right-wing talk radio, Fox News, and Breitbart.com; movement conservatism has declined in the new, fragmented information ecosystem. Meanwhile, the dearth of ideological diversity harms both the media and academia, which are less rigorous than they would otherwise be, less likely to grasp conservative principles, and less likely to unify people.

The left can help reintegrate conservatives into institutions where they face a hostile climate. This process should be eased by the realization that authoritarian psychology, not conservative ideology, is the main driver of intolerance. In fact, traditional conservatism has the potential to combat intolerance: Laissez-faire conservatives are predisposed to reject coerced sameness. Status quo conservatives, meanwhile, can be an important check against new demands for intolerance.

Reformers on the left and right alike must give up the fantasy that humans are blank slates who can be overwritten with ideal values, however discomfiting or disappointing the realization may be.

As Stenner puts it, we can moralize all day about how we want ideal citizens to be, “but democracy is most secure, and tolerance is maximized, when we design systems to accommodate how people actually are.”

Nor can we take for granted that the next generation will overcome today’s divisions. After studying post-conflict Bosnia, Borislava Manojlovic, a researcher at Seton Hall University, found that members of the generation that started the Balkan wars now tend to be more tolerant toward one another than their children are. A 24-year-old explained why to World Affairs: “The people who fought the last war had lived together for forty-some years,” he said. “They still have memories of the good old times … We are a ticking time bomb.”

In the U.S., the World War II generation worked together by necessity. Perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised that, as that generation passed from the scene—succeeded by Baby Boomers, who began coming of age in the polarized 1960s—the country began to splinter. This fragmentation has brought more intolerance. Indeed, the Baby Boomers’ kids, the Millennials, are more likely than past generations to favor political intolerance in the form of free-speech restrictions.

Even if America is unlikely to descend into another civil war, our present trajectory carries huge risks. Millennials may take charge of the country without much memory of a functional Congress, tolerant public discourse, or social circles that transcend our atomized subcultures. Today’s college students can scarcely recall a life free of internet trolls!

The good news is that counteracting polarization is not a lost cause, if only Americans are circumspect enough to recognize what we have in common. American identity—unlike, say, Danish identity—does not revolve around shared ancestry, or a culture that is existentially threatened by changing demographics. Rather, it is grounded in a shared if unrealized aspiration to guarantee the rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

Nonauthoritarians on the left and right will always clash on how to achieve that goal. But better to cooperate with those you believe to be misguided than to risk mutual destruction.

0 General Document comments

0 Sentence and Paragraph comments

0 Image and Video comments

General Document Comments 0