In the Field: Restoring Big Egg Marsh

Author: U.S. National Park Service - Northeast Coastal and Barrier Inventory & Monitoring Network

“In the Field: Restoring Big Egg Marsh (U.S. National Park Service).” National Parks Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, https://www.nps.gov/im/ncbn/big-egg-marsh.htm.

0 General Document comments

0 Sentence and Paragraph comments

0 Image and Video comments

Marsh Sounds

CREDIT / AUTHOR: Bridget Ye / NPS DATE CREATED: 2021-07-29

In 2002, an experiment began to restore a salt marsh at Gateway National Recreation Area. 20 years later, scientists return to see how it’s doing.

The Yolk of Gateway

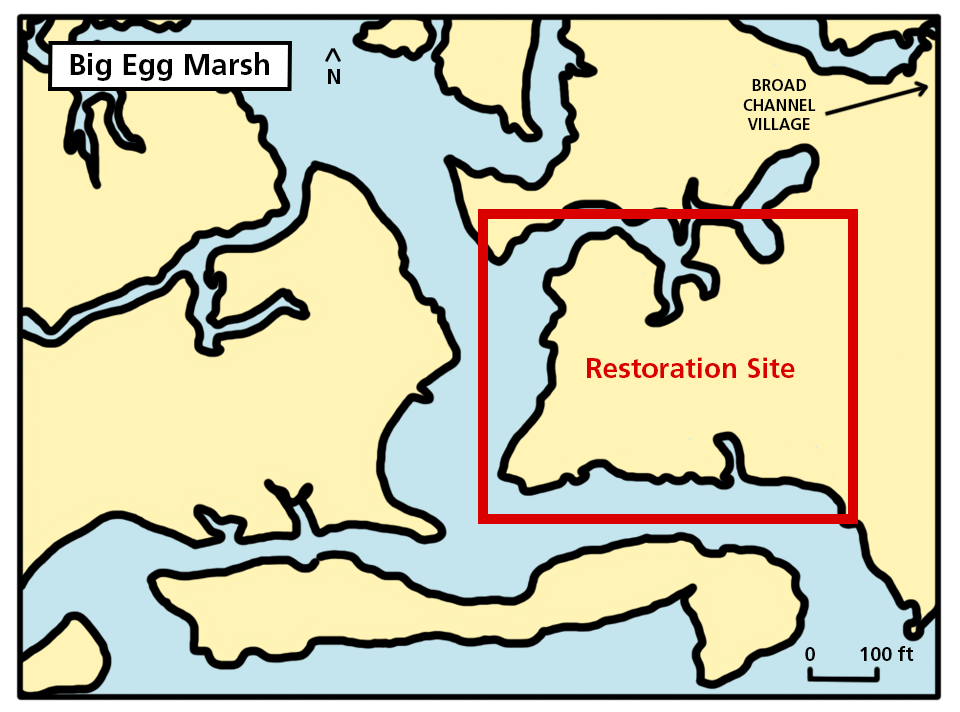

Big Egg Marsh is one of thirteen salt marshes remaining in New York City’s Jamaica Bay. A part of Gateway National Recreation Area, Big Egg has been the site of an experiment since 2002. The experiment is one of restoration. The salt marshes in Jamaica Bay have been rapidly disappearing since 1924. Given Jamaica Bay’s long history of contaminated waters and urbanization, combined with accelerating sea level rise, scientists expect most of its salt marshes to disappear within decades, if left alone.

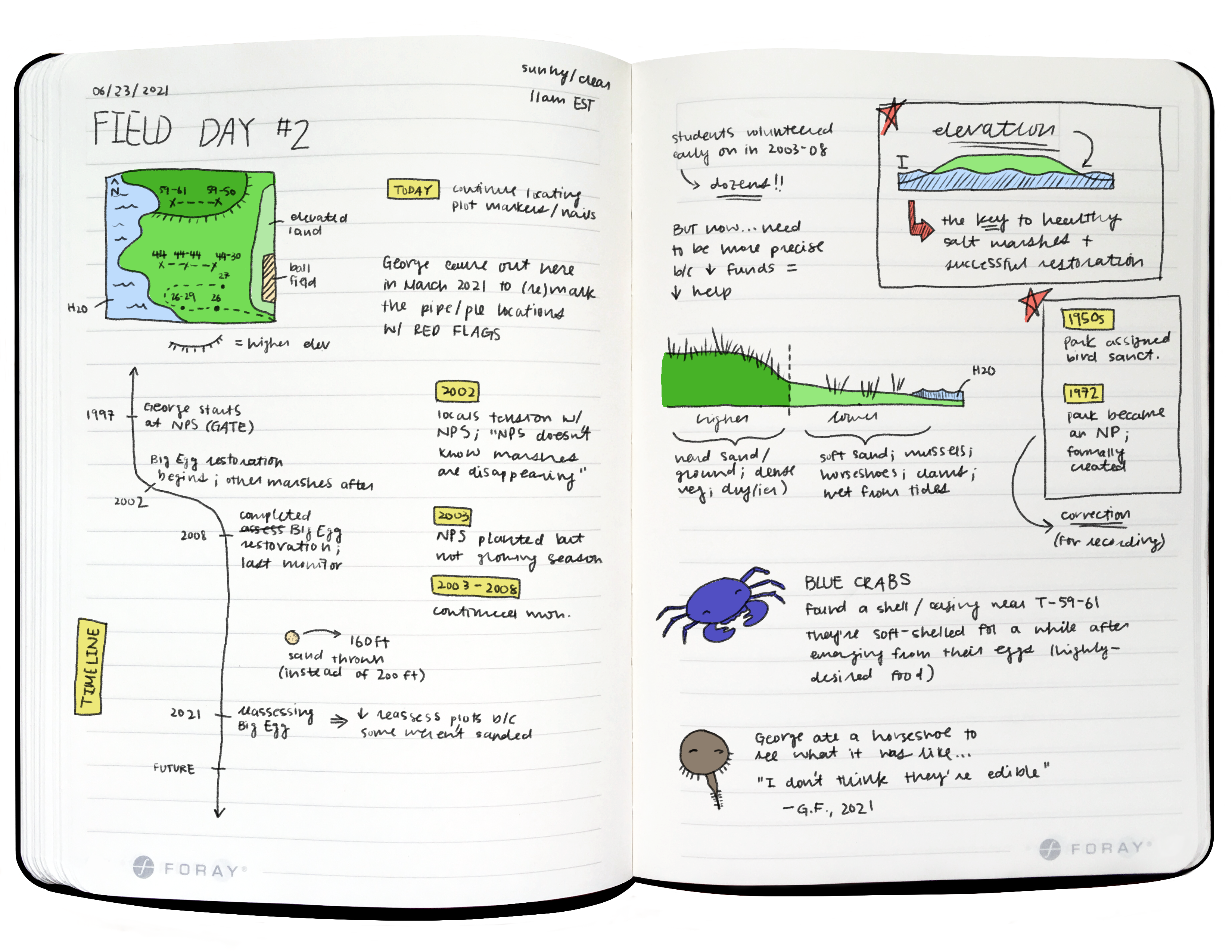

In 2000, the residents of Jamaica Bay’s Broad Channel Village voiced concerns over the marsh losses they had witnessed for decades. When the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation first used GIS technology to analyze the bay’s history, their data confirmed the residents’ concerns. With that, Gateway NRA decided to give restoration a try. Jamaica Bay, after all, was to be protected and conserved by federal law ever since Gateway NRA was founded in 1972. Something had to be done. Park scientists chose Big Egg Marsh as the site for the experimental restoration, and planning began in 2001. By 2002, restoration was underway.

The Experiment

When Gateway NRA set out to restore Big Egg, park biologist, Dr. George W. Frame, was among the primary researchers leading the experiment. For habitats like salt marshes that survive at the boundary where land meets water, “the critical thing,” George says, “is elevation.” Because a marsh is subjected to tides, it’s at risk of drowning if its surface isn’t high enough above water. And if it drowns, whatever vegetation and wildlife it sustains would disappear with it.

The primary goal of Big Egg’s restoration was, therefore, to improve marsh elevation and maintain it. To raise the elevation, clean sand was dredged from a nearby creek and sprayed over a one hectare area of Big Egg in August 2003. This thin layer of sand slurry added up to 20 inches of height. Now, this new elevation had to be maintained.

In October 2003, National Park Service scientists and 100 volunteers planted 20,000 seedlings of smooth cordgrass throughout Big Egg where sand was sprayed. Smooth cordgrass (Spartina alterniflora) is a plant species that actually thrives in the high salinity of salt marshes. In fact, its abundance supports the longevity of a salt marsh. Its roots trap sediment that, over time, accumulates to form a nutrient-rich peat. This peat provides a robust foundation that promotes even more plant growth. With the experiment fully set up by the end of 2003, monitoring could begin.

Monitoring Up Close

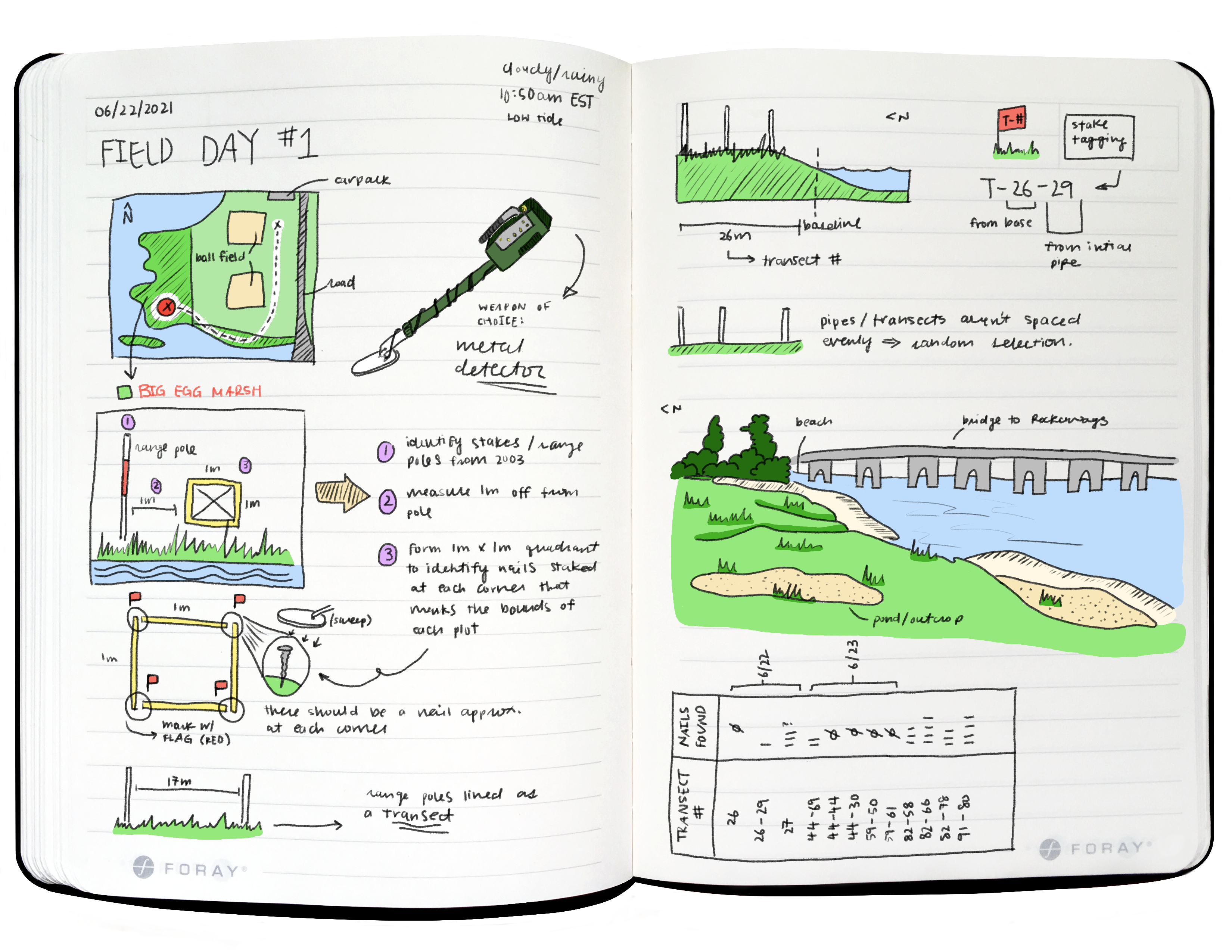

Gateway NRA scientists marked out a series of one meter by one meter plots throughout Big Egg. Every time they collected new observations, they would return to these same plots to gather the same types of data, using the same collection methods. What is the current elevation? How many individual plants are there? What materials are in the soil? Which animals are roaming around? Repeating this scientific process over time is monitoring, and only time would tell whether restoring Big Egg was a success.

To keep track of where plots were, scientists mapped Big Egg and divided it using a vertical line, called the baseline; and multiple horizontal lines, called transects. The baseline was drawn north to south, along the east of Big Egg. Transect lines start at the baseline and run east to west, perpendicular to the baseline. A long white plastic pipe (about 3 meters long) was first anchored in the ground at the transect starting point, and then more pipes were placed every ten meters in a straight line, going west from the starting point.

Now, for the plots. Plots were allocated along the southern edge of each transect and at random intervals. To mark the boundaries of each plot, an eight-inch galvanized nail was hammered into the ground. The plots were placed consistently to the south of each transect so researchers could move around the marsh without accidentally stepping into a plot. Doing so could impact the vegetation, and therefore impact how accurately collected vegetation data reflects the marsh’s actual conditions.

The plots were also placed randomly so scientists can gain a bigger picture of how Big Egg has responded to restoration efforts. Maybe plants didn’t thrive as much in one area compared to another. Or wildlife prefers the environment in this area over that. Collecting data from different areas can reveal patterns of change on a smaller-scale plots and the larger-scale marsh. All together, Big Egg on a map looks similar to rows of pennant garlands on a wall. Imagine the edge of the wall as the baseline, each garland string as a transect, and each pennant a plot.

Once monitoring began in 2004, George and other Gateway NRA scientists returned to Big Egg multiple times every year until 2008. In this short-term period, they observed both negative and positive change. For one, many smooth cordgrass seedlings were eaten by geese, washed away by tides, or suffocated under marine debris like straw, big logs, bottles, and plastic bags. Hardy as ever, though, the smooth cordgrass did thrive despite these setbacks. New seedlings sprouted on their own, and saltmeadow cordgrass or salt hay (Spartina patens) began appearing, too. Two years into Big Egg’s restoration, over 80% of its experiment site was vegetated and healthy.

While new observations haven’t been recorded as frequently since 2008, monitoring still continues to better understand the longer-term consequences of restoration. So, in 2021, over a decade after short-term monitoring research and nearly two decades since the restoration began, George returns to Big Egg again to see how it’s doing.

Field Day #1: Meeting George

This summer, George has two Student Conservation Association interns assisting him with fieldwork. Before collecting any new data, the first thing George and the interns have to do is find the one meter by one meter plots that were marked way back in 2003. Once they do that, they can begin collecting vegetation and soil data.

George takes the interns north along the baseline and west across each transect, taking care to walk along the northern edge of each transect so they don’t accidentally step in a plot. At each plot, the interns use a metal detector to look for the eight-inch galvanized nails at each corner. The nails, however, had been impacted by the harsh conditions of the marsh. Most are nowhere to be found. It’s likely they were washed away or sank deeper into the peat during high tides, or rusted beyond detection. Best case scenario, the nails were rusted down to the size of your thumb and just barely holding on in the ground. A red flag is placed where a nail is found. Or, if a nail isn’t there, a red flag is placed where it should’ve been at each plot corner.

On this day of fieldwork, George and the interns didn’t have much success finding the old nails. Instead, they looked for plots using the white transect pipes. Like the nails, the pipes were subjected to conditions of the marsh. Most were frozen into winter ice at the marsh surface and then sheared off when ice moved, left as tiny white stubs just a few inches tall. But they were markers, nonetheless, and George and the interns used them with success to measure the location of the plots and mark each corner with red flags.

At each corner of a plot, an eight-inch nail was hammered into the soil to mark the plot boundaries. The interns use a metal detector to look for them, but the nails had been impacted by the harsh conditions of the marsh. Most of the nails are nowhere to be found. It’s likely they were washed away or sank deeper into the soil during high tides, or rusted beyond detection. Best case scenario, the nails were rusted down to the size of your thumb and just barely holding on in the ground. A red flag is placed where a nail is found. Or, if a nail isn’t there, a red flag is placed where it should’ve been at each plot corner.

On this day of fieldwork, George and the interns didn’t have much success finding the old nails. Instead, they looked for plots using the white transect pipes. Like the nails, the pipes were subjected to conditions of the marsh. Most were frozen into winter ice at the marsh surface and then sheared off when ice moved, left as tiny white stubs just a few inches tall. But they were markers, nonetheless, and George and the interns used them with success to locate the plots and mark each corner with red flags.

Snack Break: Marsh Restoration

CREDIT / AUTHOR: Bridget Ye / NPS DATE CREATED: 2021-07-28 Audio Transcript

AUDIO TRANSCRIPT

Interviewer: So, can you explain the process of how you restore a marsh? Is that complicated?

Dr. George W. Frame: Well, the critical thing is elevation. If you just came out here and planted new plants in bare spots, they wouldn’t do any better than the plants you see now. This is not a bad elevation here. If we were lower down, in that marsh over there, which is lower elevation, the control site, it has to have new sand placed on it to make it higher. And when you get the right elevation, then the plants will thrive. And that’s the whole point behind bringing sand from the channel deepening projects and elsewhere.

The sand is cleaner than any other kind of mixture of sands, silts, sediments, clay. All those fine particle things have a lot of contaminants bound to them but the sand is relatively free of contaminants, so you’re bringing clean sand, like 95% sand and you raise the elevation. And it’s kind of mimicking the natural process because in the natural salt marshes, the waves during storms or full-moon tides wash up sand in the piles that are higher than normal. And those high spots are where grass takes root and you see it starts growing and then it keeps expanding over the years to make new salt marshes. Bigger and bigger every year. And also, in the process, it makes an ideal nesting site for horseshoe crabs because they like that elevation that is optimal for marsh plants. And then placing sand on top of these lower marshes, it contains the contaminants that are there. It excludes them from the current environment. It just puts them in “cold storage” for future centuries.

So all these projects in restoring marshes in the bay is actually improving the quality of the bay bottom and the marshes by covering the contaminated materials with cleaner materials all the time. Cleaner and cleaner and cleaner. The big restorations that the Army Corps of Engineers does have a much thicker layer of sand than we have here and it really keeps the—oh this willet over there has a nest over there. Anyway, it keeps the sediments contained so that they don’t wash out into the present environment. But it’s inevitable some time in the future a century from now, more or less, that there will be some kind of a change in the environment that allows sediments to liberate some of the contaminants. But for us, and for the next few generations, it makes everything cleaner and better.

Fieldwork at Big Egg Marsh

Gateway NRA scientist, Dr. George W. Frame, conducts fieldwork with two interns at Big Egg Marsh in Jamaica Bay. They are locating plots that were placed in the field in 2003 as part of a marsh restoration project.

Field Day #2: Finding More Plots

A Brief Interruption

DATE CREATED: 2021-07-28

AUDIO TRANSCRIPT

Dr. George W. Frame: So just those were two different—there was real contrast between those two different countries—[Metal detector screech]. Interviewer: Do you mind? Intern: I’m very sorry. Very sorry.

Much of day two of fieldwork is spent in a higher elevation area of Big Egg. Up here, smooth cordgrass is more abundant, the ground is firmer and drier, and the area generally seems less impacted by the water. George and the interns continue to locate the remaining plots. After hours of scanning the ground with a metal detector and prodding into the soil with trowels to look for nails, the hard work pays off. To everyone’s excitement, the interns manage to find multiple nails today. At two of the plots, they even find all four nails, one at each corner!

Now that all the plots are found and marked with red flags, the second day of fieldwork wraps up early. With the spare time, George talks to the interns about Big Egg’s neighboring marsh, Little Egg Marsh, and a not so lawful Fourth of July party that took place there. The interns learn about the invasive Asian Shore Crabs (Hemigrapsus sanguineus) and express hopes of sighting native Diamondback Terrapins (Malaclemys terrapin) that live around Big Egg. To listen to George speak of Jamaica Bay, surrounded by the sights and sounds of marshland, was a refreshing conclusion to another hot day in the field.

Snack Break: Little Egg Marsh

DATE CREATED: 2021-07-29

AUDIO TRANSCRIPT

Dr. George W. Frame (GF): Oh, it’s a pity to leave the marsh so early. It’s so nice out here. Intern 1: It is really nice. Intern 2: What are those trees past the— GF: That’s Little Egg marsh. Intern 2: Little Egg marsh. And is there any monitoring being done there or—? GF: No. There’s salt marsh on the south side of it but that’s all dredged soil put there back in the 1950s. Intern 1: That’s interesting. GF: That’s a great nesting area. Intern 1: Do people ever go there? Like take a boat there? GF: Legally or not legally? Intern 1: Well, I’m assuming—cause you said this [Big Egg Marsh] was the only one people can legally go on right? GF: Oh, yeah. About five years ago, there was a big Fourth of July party on that island. Intern 1: Oh my god. Intern 2: Oh my god. GF: The police put a cap on that and they haven’t been back since. Intern 1: Ignoring the terrible environmental effects of that, that seems like a pretty cool party, to be honest. GF: Well, people were complaining they had to walk through the dirty water to get up on the sand. Intern 2: Their fault. Intern 1: I wonder how much garbage they left there, too. Intern 2: Isn’t that their fault for going there?

Snack Break: Crabs & Turtles

DATE CREATED: 2021-07-29

AUDIO TRANSCRIPT

Dr. George W. Frame (GF): This looks like a—it’s not the right color. I mean when they’re alive, they’re a deep green, a greenish black. But it looks like a Hemigrapsis [Asian Shore Crab], which is an invasive crab that came here about, oh, 30 years ago and now there are millions of them in the bay. And they compete. They eat other crabs. They’re just considered an invasive, highly invasive species that’s not desirable. Intern 1: Are there any turtles in this? I know like—on this particular marsh, are there any turtles? GF: I haven’t seen a live turtle here. I’ve seen gulls dropping them on the marsh. Intern 1: Oh my god. GF: But I’m sure they use the marsh edges for feeding in the creeks, those tiny creeks around the marsh. But currently, the rim road of the West Pond currently gets about 300 turtle nests per year. Intern 1: Oh my gosh, that’s cool. GF: At least, maybe more. But 20 years ago, it was more like 2,000. Intern 1: Wow. GF: So the numbers are greatly declining— Intern 1: Yeah. GF: —in this part of Jamaica Bay. But at Kennedy Airport, has huge numbers of turtles coming onto the shores. Intern 1: Oh interesting. Intern 2: I actually read—heard about that. They had to slow down flights because turtles were on their tracks, on their plane tracks, like herds of them. GF: Yeah, they’re getting thousands of turtles there. Intern 2: Cause they always go back to the water at like in the morning, the early morning. I remember in Wantagh Park, you’d always see multiple lines of turtles going into the water at like 5am. GF: They come onto the rim road. Quite a few of them lay their nest—their egg in holes on the rim road actually. And others adjacent to the rim road. During June and July, you spend two or three half days there, you’ll probably see some nesting terrapins.

What Now?

That’s a good question.

George and the interns will return to Big Egg over the rest of this summer, as other scientists had in the years after restoration began. The data they collect, now that they’ve found all the plots, will continue the legacy of monitoring at Big Egg. With it, scientists will gain the first insight into the long-term impacts of Big Egg’s restoration.

George has witnessed the last two decades of change since the restoration began. In his eyes, it’s been a success. As with projects, experiments, and many things in life, there are aspects that could’ve been done differently or better. But even so, the effort to restore one of the remaining salt marshes in Jamaica Bay has been rewarded with optimism, hope, and resilience at least for the next few generations. Restoring Big Egg has also paved way for other Jamaica Bay restoration projects. Together, these efforts have restored over 150 acres of marshland in the bay.

Monitoring will continue into the even longer-term future, and the changes we see at Big Egg will depend on what happens in greater New York City, the greater northeastern U.S. coast, the greater Atlantic Ocean, and greater society. Restoration, even one with positive impacts, is still a temporary solution. The act of restoring itself is an indicator that a system has reached a kind of threshold, close to permanent or irreversible change. It’s an effort that often requires funding, expertise, time, and the difficult task of trying to predict the future. Restoring Big Egg was an experiment that used the particular technique of spraying a thin layer of sand to restore a salt marsh. An experiment of this kind “probably won’t be repeated for some time,” George says, “But it’s nice to know.” That is, it’s nice to know it could be done with a measure of success, if need be.

General Document Comments 0

0 archived comments