The Massacre of Black Wall Street

Author: Writing: Natalie Chang Illustration: Clayton Henry / Colorist: Marcelo Maiolo

Chang, Natalie, Clayton Henry, Marcelo Maiolo, “The Massacre of Black Wall Street.” The Atlantic, Atlantic Media Company, 2019, https://www.theatlantic.com/sponsored/hbo-2019/the-massacre-of-black-wall-street/3217/.

0 General Document comments

0 Sentence and Paragraph comments

0 Image and Video comments

In 1921, White rioters destroyed a beacon of Black prosperity and security.

Watch this GIF to see five suggestions for responding.

why did the white rioters destroyed the beacon of the black prosperity

why are they so many people 300 people is way to many people to be killing, then your them homeless with no food home or nowhere to be warm or to live

I agree it was not that serious for to it go that far as destroying black people community

why did the white rioters destroy the beacon of black prosperity

White mobs shattered a gleam of Black accomplishment and security.

but why? for no reason at all. nobody was harming them or their families in any way. the black community should’ve been able to grow their businesses and thrive just like everyone else.

To understand the context of this text, it’s essential to examine three crucial sentences:

1. “In 1921, White rioters destroyed a beacon of Black prosperity and security.”

2. “American history during this time [was marked by] race massacres.”

3. “A beacon of Black prosperity and security” refers to a thriving community known for its economic success.

These sentences collectively allude to a pivotal event in American history—namely, the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921. Here’s why each sentence is important:

1. The first sentence specifies the year 1921, which is important because it places the event within the broader historical context of the post-World War I era, a time of economic, social, and racial tension in the United States.

Background Info: The Tulsa Race Massacre occurred from May 31 to June 1, 1921, in the Greenwood District of Tulsa, Oklahoma, often referred to as “Black Wall Street” because it was one of the wealthiest Black communities in the United States at the time. The massacre was one of the deadliest episodes of racial violence in American history.

2. The sentence about race massacres highlights the prevalence of racial violence during this period. Post-war America experienced a rise in such violence, often spurred by deep-seated racism, economic competition, and widespread white supremacist ideologies.

Background Info: The early 20th century, and especially the period after World War I, was marred by a series of race riots and massacres across the United States. This era is sometimes referred to as the “Red Summer” of 1919, marked by numerous race riots in more than 30 cities across the country.

3. The mention of the “beacon of Black prosperity and security” underscores the fact that the Tulsa community was a rare example of Black financial independence and success in an era of severe racial oppression and segregation under Jim Crow laws.

Background Info: The Greenwood District was home to a highly successful African American community, with thriving businesses, schools, and churches. The destruction of this community during the massacre included the loss of over 1,000 homes and numerous businesses, and the death toll is estimated to be in the hundreds.

To understand this period more deeply, relevant resources might include books such as “The Burning: Massacre, Destruction, and the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921” by Tim Madigan, or “Black Wall Street: From Riot to Renaissance in Tulsa’s Historic Greenwood District” by Hannibal B. Johnson. Additionally, the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture provides online resources about the Tulsa Race Massacre and the historical context of such events.

Now, with this background knowledge, I invite you to reflect on the historical significance of the Tulsa Race Massacre. Consider how the destruction of an affluent Black community might have broader implications for race relations in America, both then and now. Upon re-reading the text, you may discover new layers of meaning in understanding the challenges and resiliency of Black Americans in the early 20th century. If more insights occur to you, please feel free to share them in reply.

Why are there so many people there? 300 people is far too many to be murdering, and on top of that, you have them living in squalor, without a place to eat, sleep, or be warm.

why did the white people just destroy everything and never rebulid

What was the point of the massacre don’t really makes sense to me

They killed as many as 300 black Tulsans, left thousands homeless, and ransacked an entire neighborhood.

This is simply because they will also believe the white person before they do the black man. Even if it wasn’t true they still would’ve went this far.

the people took the woman words over the man that was accused for the so called act he committed towards the woman.Tulsa just didn’t like Greenwood so they took ever chance they could to take every thing from them

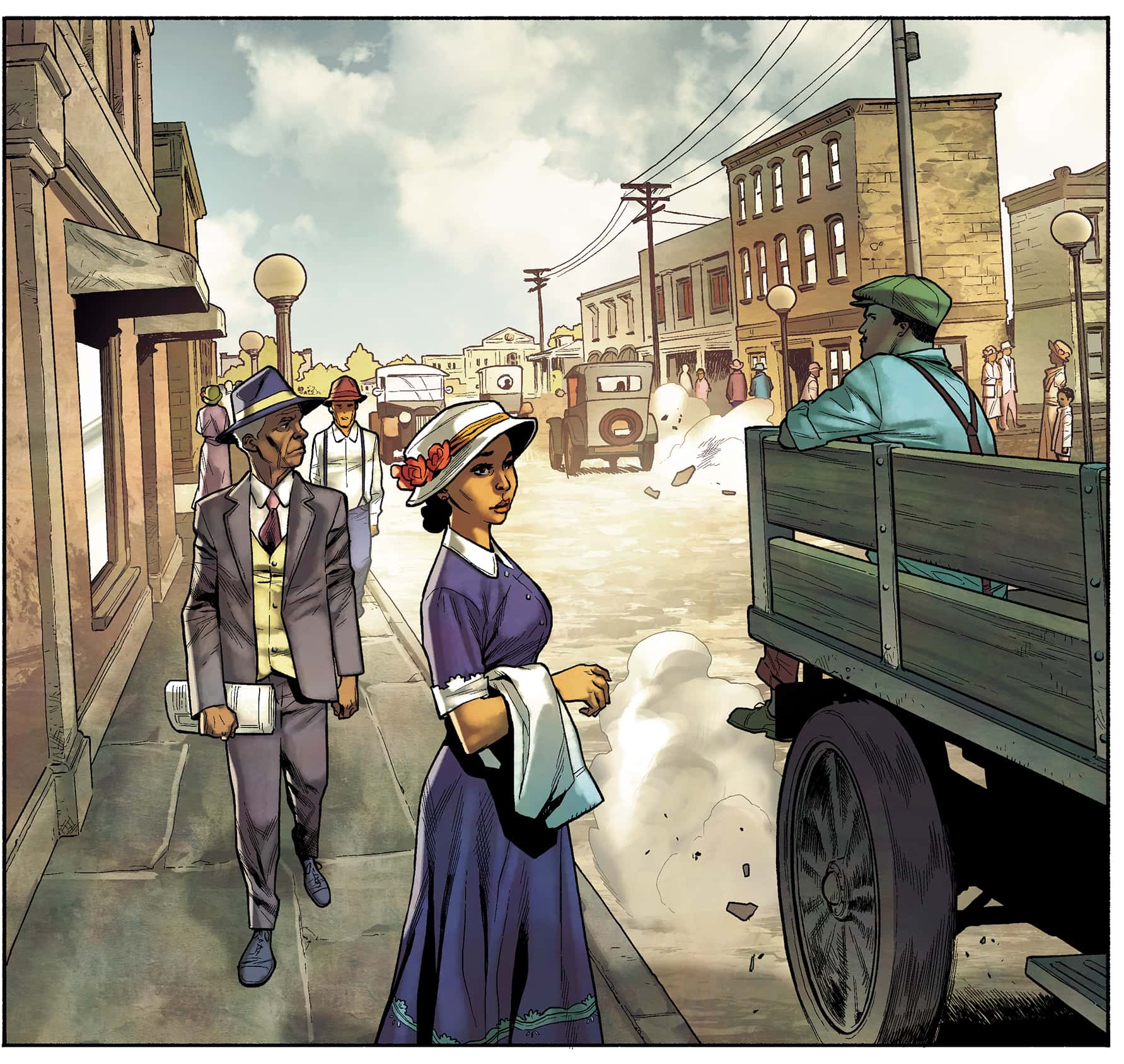

Its a wealthy area, you can tell by the way people are dresses and the surrounding.

I feel like greenwood was a safe place for black people. It was a good neighborhood. Everybody was didn’t have to worry about anything

At the time, there were no prosecutions of the instigators. Almost a century later, there have been no reparations.

I find this interesting because they destroyed a community and then later they still didn’t pay for what they destroyed. I wonder if this was a white community that was destroyed would they have paid them? Or maybe they wouldn’t even have done this to white people because during segregation white people were always put in the upper class and African-Americans were put in the lower class. So for them to be successful African-Americans in the upper class they got jealous and wanted to destroy the thriving black community and knew that they wouldn’t have to repay or be held accountable because of the racism.

its crazy how they did a lot of damged and didnt pay or rebuild it

This is what happened, and why it still matters today.

This is all true:

In 1921, about 11,000 Black residents lived in the neighborhood of Greenwood, north of the Frisco railroad tracks in Tulsa. It was self-contained and self-sufficient: Black-owned grocery stores, banks, libraries, hotels, movie theatres, and more lined the neighborhood’s main thoroughfare, Greenwood Avenue.

who is writing this? Why did they hate us this bad? Black people had everything that the whites. We was living lavish.So when one thing went wrong involving`with a black and white person. that was the chance for the whites to end every last bit of anything black people had

This makes me think about the book Magic City by Jewell Parker Rhodes when Samuel was on the train. I wonder if it was this train or a different one? And was this train a segregated train?

It was a thriving commercial district. And as much as it could be, it was also a safe space.

This makes me connect back to when the Dawes Act of 1887 authorized the government to divide tribal territories into allotments for individual Native Americans, which included Black members. And it was said that it was a safe place for African-Americans to go to and that is why many African-Americans went there and build more than 50 Black townships in Oklahoma. So it being a safe place was really what drew African-Americans to go to the land and build all the businesses.

his is a very complex issue and it can easily overwhelm someone when they try to comprehend the full depth of the situation. It is like trying to weigh the difficulty of a long-distance marathon – the amount of exhaustion and uncertainties looming ahead can be quite overwhelming. For Blacks in America, this has been a marathon of sorts, with hateful violence, oppressive laws, and unequal institutions stretching out for hundreds of years, and the lack of justice and recognition these situations brought to bear year after year taking its toll on the community. While certain strides towards progress have been made, it is as if the starting gun of the marathon has yet to sound and the course continues its long stretch ahead. The tragedy of the matter is that many in the Black community have had to run this race with their lives, only to be killed along the path for no other reason than their race. This is unacceptable and requires us to work together and strive towards a new and equitable outcome for everyone.

This is true as well:

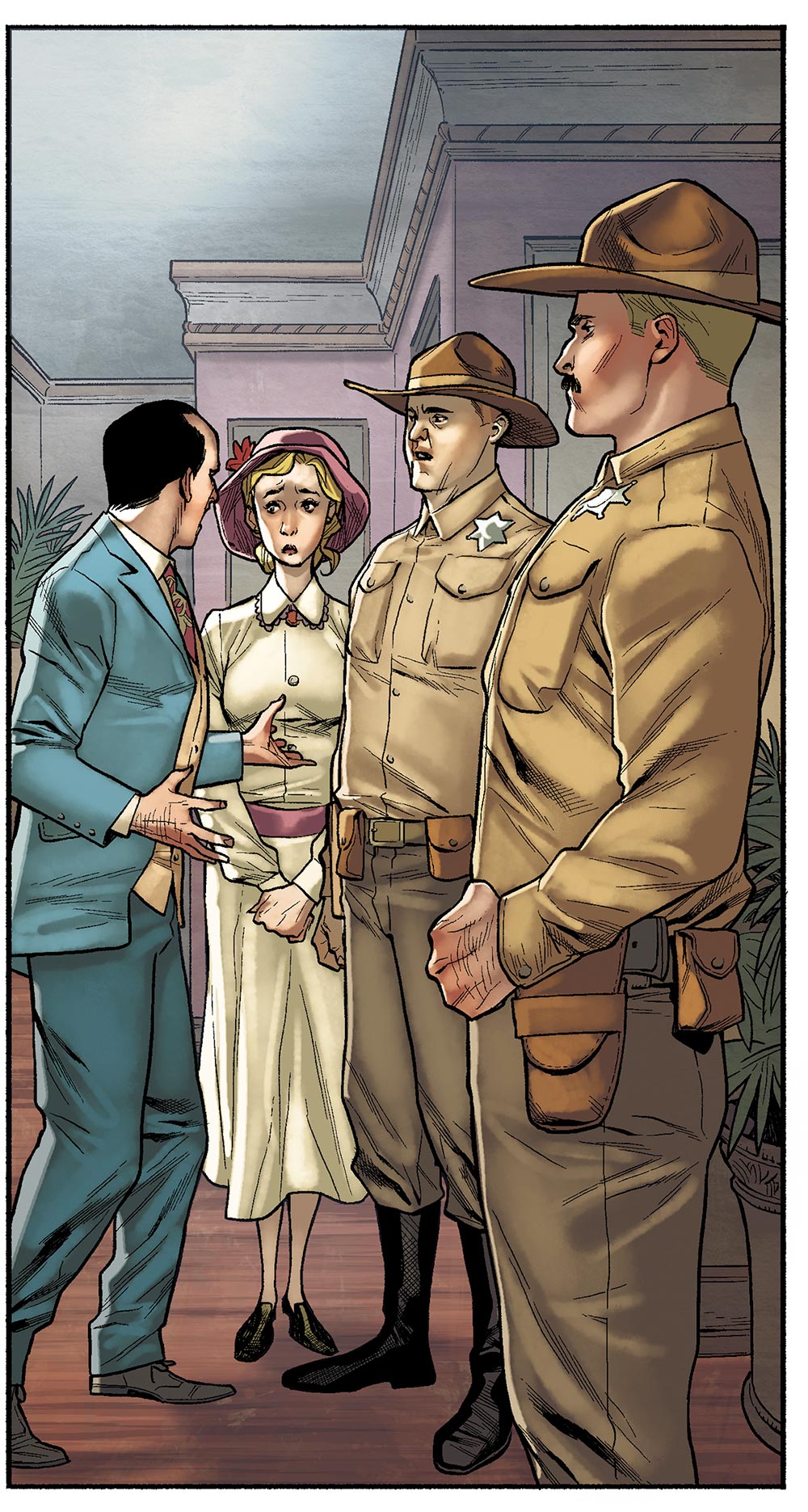

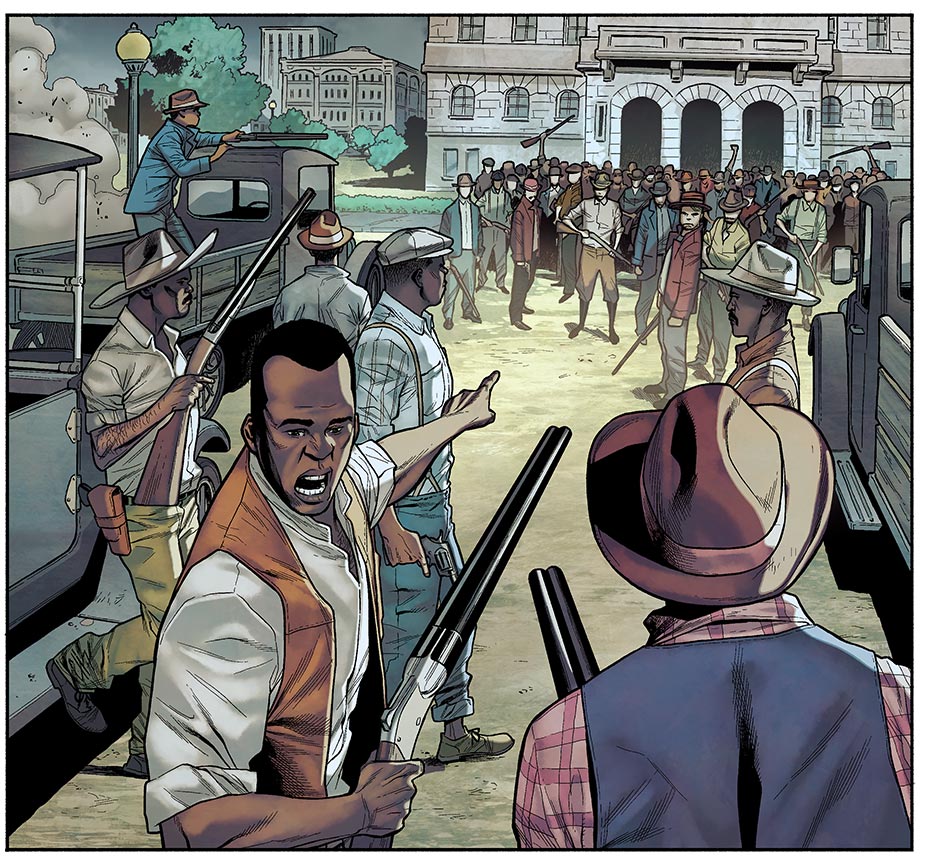

In the period from 1911 to 1921, 23 Black Oklahomans were lynched by White mobs. As part of the Jim Crow South, Tulsa was highly segregated, its Black voters suppressed and Black residents scapegoated. A sense of frontier lawlessness lingered across the state: In Tulsa, a vigilante group calling themselves the Knights of Liberty had for years been ambushing and forcibly exiling anyone they considered a radical. In 1920, a mob of hundreds of White Tulsans stormed the county courthouse to take a White prisoner into their own hands; they lynched him that night, facing almost no interference from the police.

Is black voter suppression still taking place today? Or are some blacks just not interested in voting because they think the system is rigged against them?

I think that black voter suppression is still taking place today because they know how raicst the system is and know how much they are against them. Of course, more African-American people vote more compared to the 1900s but I think some African-Americans don’t want to act like it is equality when the system is still against them and don’t want to see them win.

I completely agree. The systemic injustices and atrocities committed against Black people throughout history were baseless and deeply rooted in prejudice and ignorance. It’s tragic how long these actions were perpetuated without any accountability. Understanding and acknowledging this past is crucial for fostering a more just and equitable society.

In the following days, Tulsa’s police chief called the lynching “of real benefit to Tulsa and the vicinity.”

Greenwood residents knew this to be true:

If the Tulsa police were not going to protect White residents, no one was going to protect Black Tulsans.

i think if people can stand up for each other they don’t need the police to protect them.

when they say that they weren’t going to protect black Tulsans that sounds pretty bad because why would they not want to be protected if they are people also.

This goes to show how much the government was not involved in what was happening within the community, it shows how corrupt the system was and continues to be. Its unfair that not only were these things happening, they were also being ignored and completely disregarded

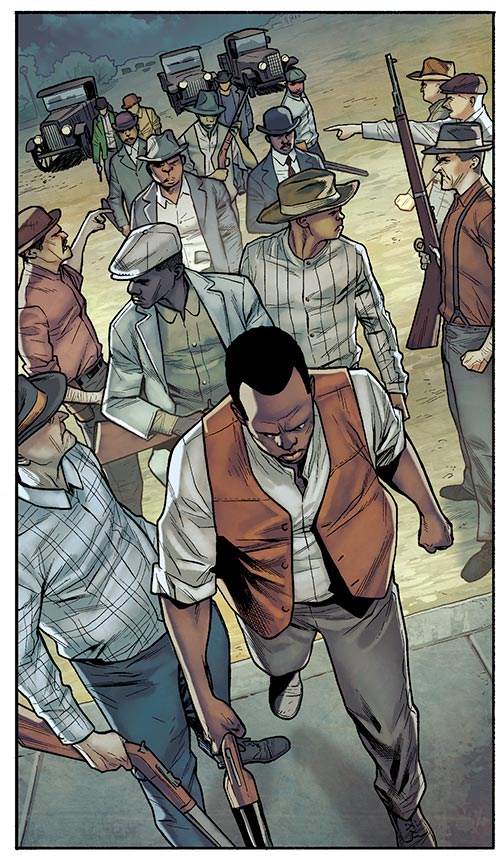

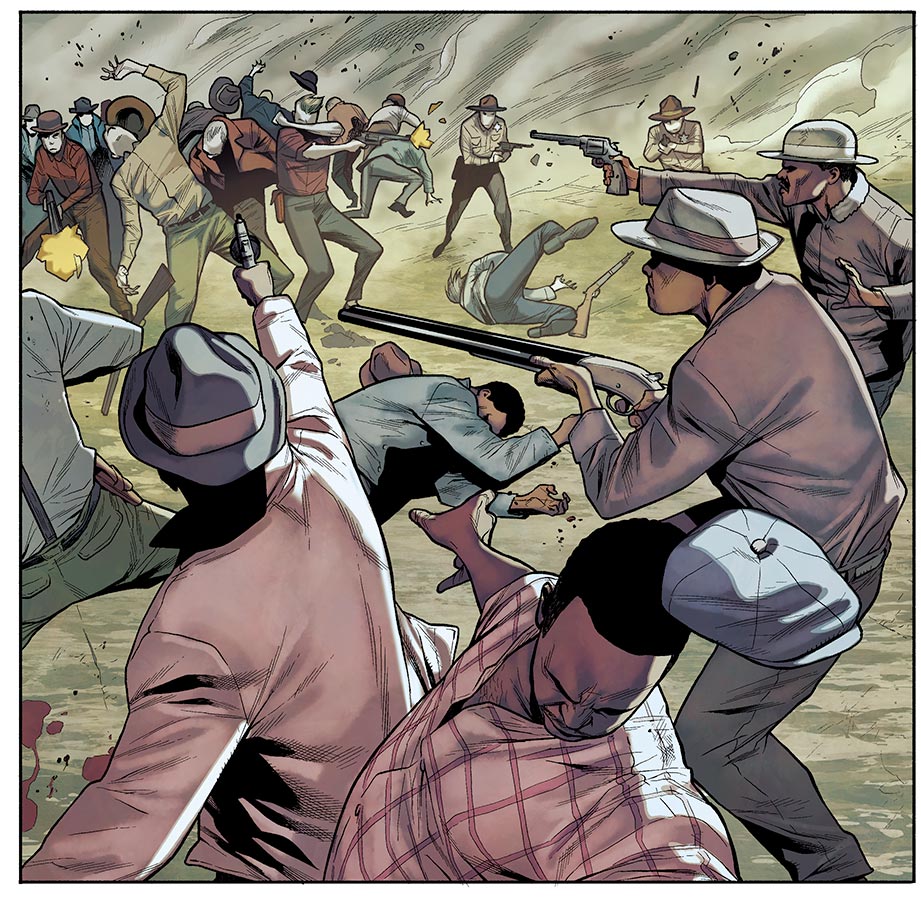

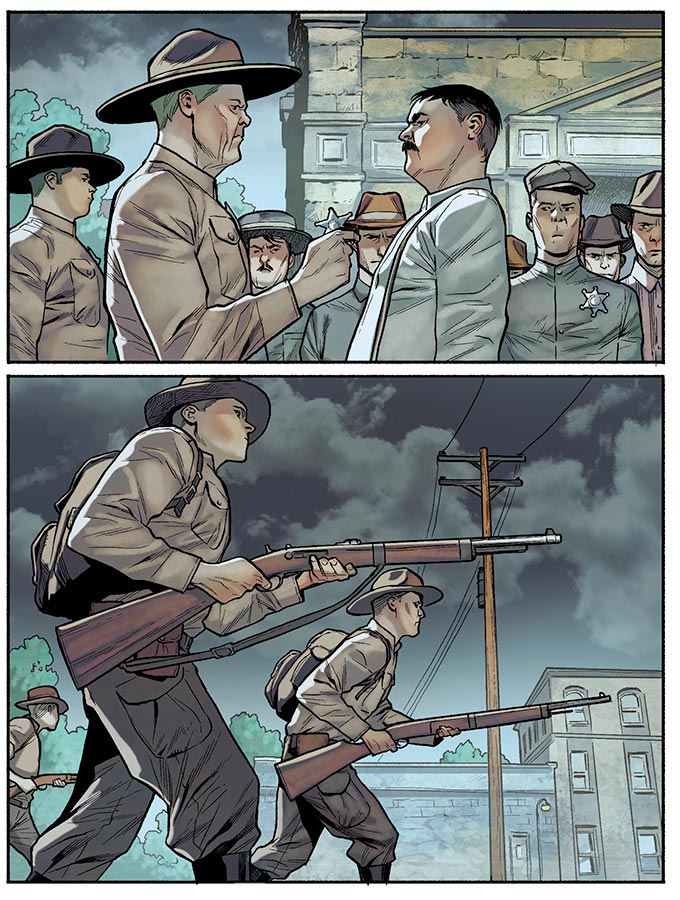

The events depicted below, to the knowledge of historians and survivors, are all true. They comprise one of the worst instances of mass racial violence in American history. Keep reading after the graphics to learn more about what happened next.

The Watchmen series on HBO opens with a scene set in 20th-century Tulsa. It’s based on real history—and we’ve depicted it in more detail below. Dialogue is based on primary accounts of the events.

The Greenwood District was such a place for African Americans. Despite the oppressive Jim Crow laws of the time, which enforced racial segregation, this area became a symbol of black entrepreneurial spirit and self-reliance. The wealth generated in this enclave led to the comparison with the prosperity of Wall Street in New York, the financial capital of the world. Hence, the moniker “Black Wall Street” resonated as a powerful testament to what the black community in Tulsa had built.

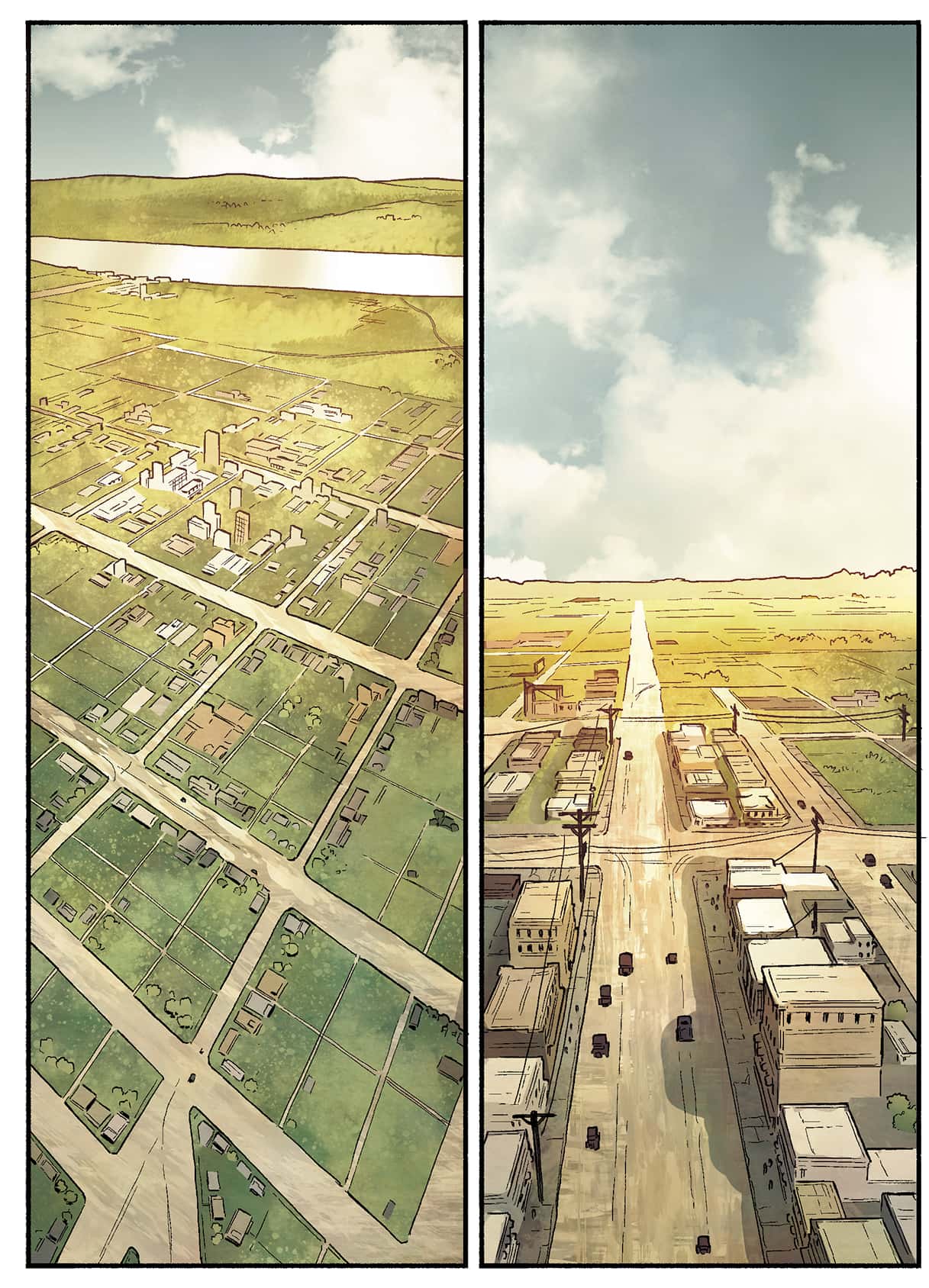

Oh, wow, this image really draws us into the scene, doesn’t it? It truly does feel like the establishing shots we see at the start of a film. When we look at the image, it’s almost as if the city is waking up, setting the stage for an unfolding story. The way it’s captured gives us a sense of anticipation, as though something significant is about to happen.

We can see the careful planning of the city in the layout of the streets, the arrangement of buildings, and the green spaces. The symmetry and order suggest a thoughtful design, an idea that everything has its place and purpose. This organized aesthetic draws our eyes to the patterns and the way the cityscape seamlessly integrates with the natural elements.

One example that stands out is the alignment of the streets and the orderly placement of structures, which highlight the deliberate planning behind the city’s design. Another remarkable detail is the way the buildings are clustered, suggesting a harmonious blend of urban life and community.

But what’s so intriguing about this image is the sense of stories untold. There’s a mystery in the air, a feeling that each building, each street has its own tale to tell. Perhaps it’s the quiet before the drama, a prelude to the lives and events that will fill this space. It makes us wonder about the people who live there, their histories, and what moments of joy or conflict might have unfolded in this very setting.

So, let’s immerse ourselves in this visual narrative and think about the chapters that this city holds within its walls. What fragments of lives and stories do you feel are lurking just beneath the surface of this meticulously planned urban landscape? What are the whispers of history we can almost hear in the air?

This area was many dominated by Black people. When white people of Tulsa envied Black people, it could have been because the Black community of Greenwood had created a self-sufficient enclave that prospered financially and culturally despite the systemic racism and legal oppression of the time.

![]()

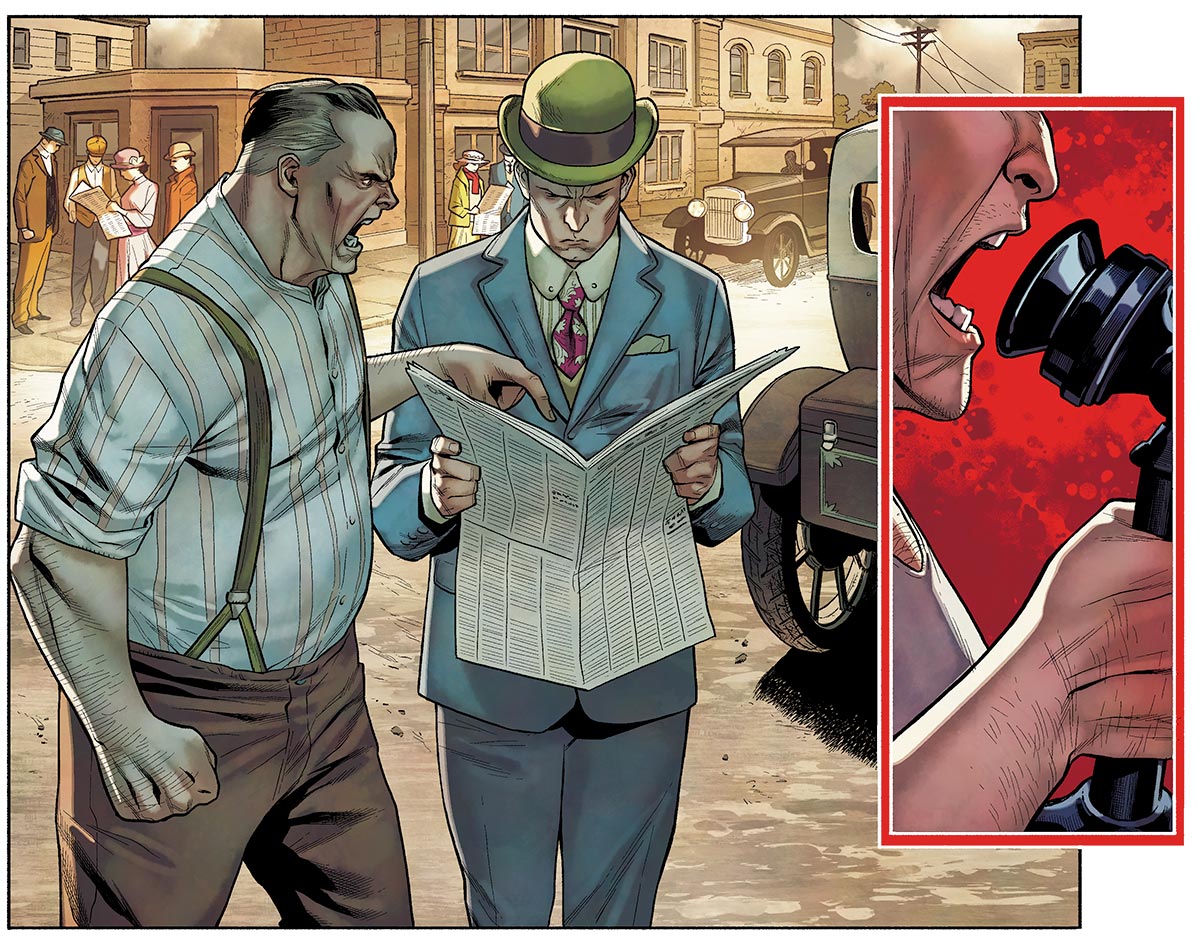

The KKK was putting down roots throughout the city. Mob justice was on the rise. Lynchings were common. And the police were often nowhere to be found.

.

I think the same thing! There are a lot times where cops witness abuse against black people but are willing to turn the other way to let the abuse keep happening.

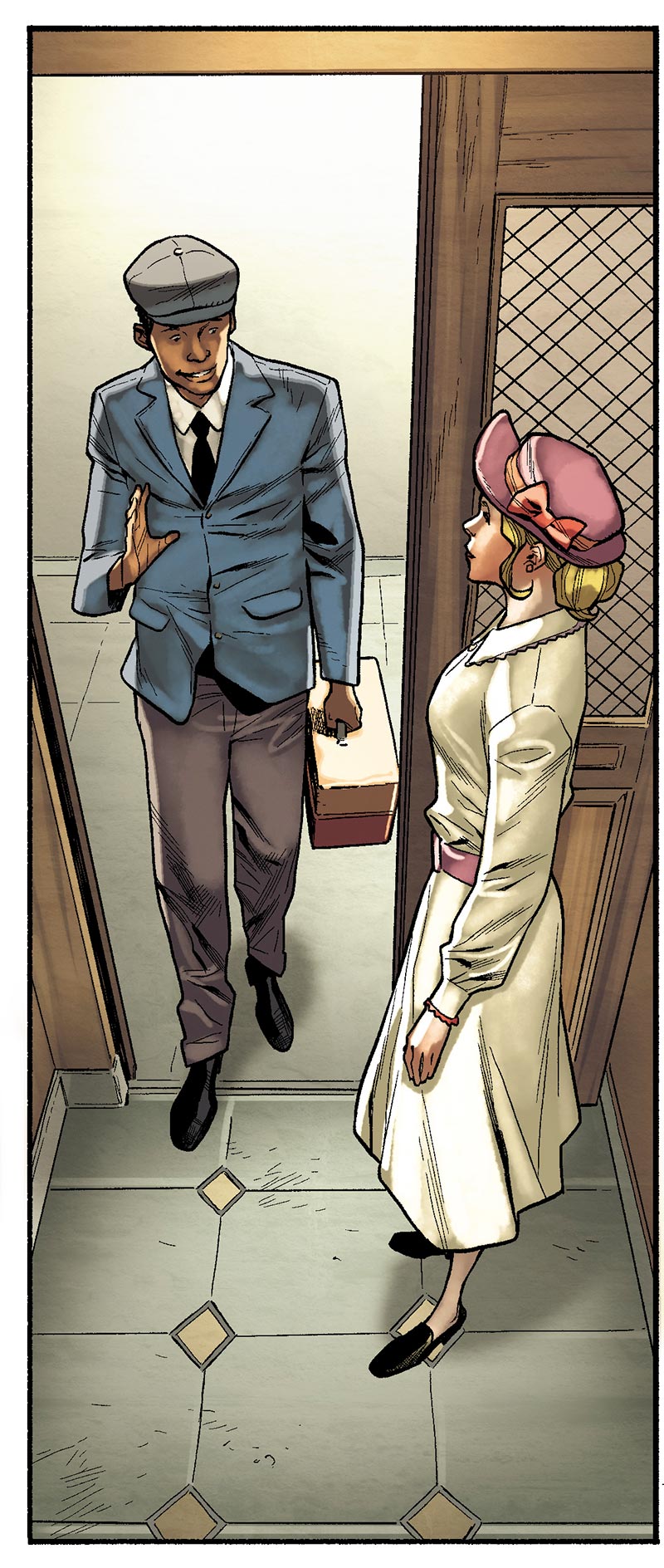

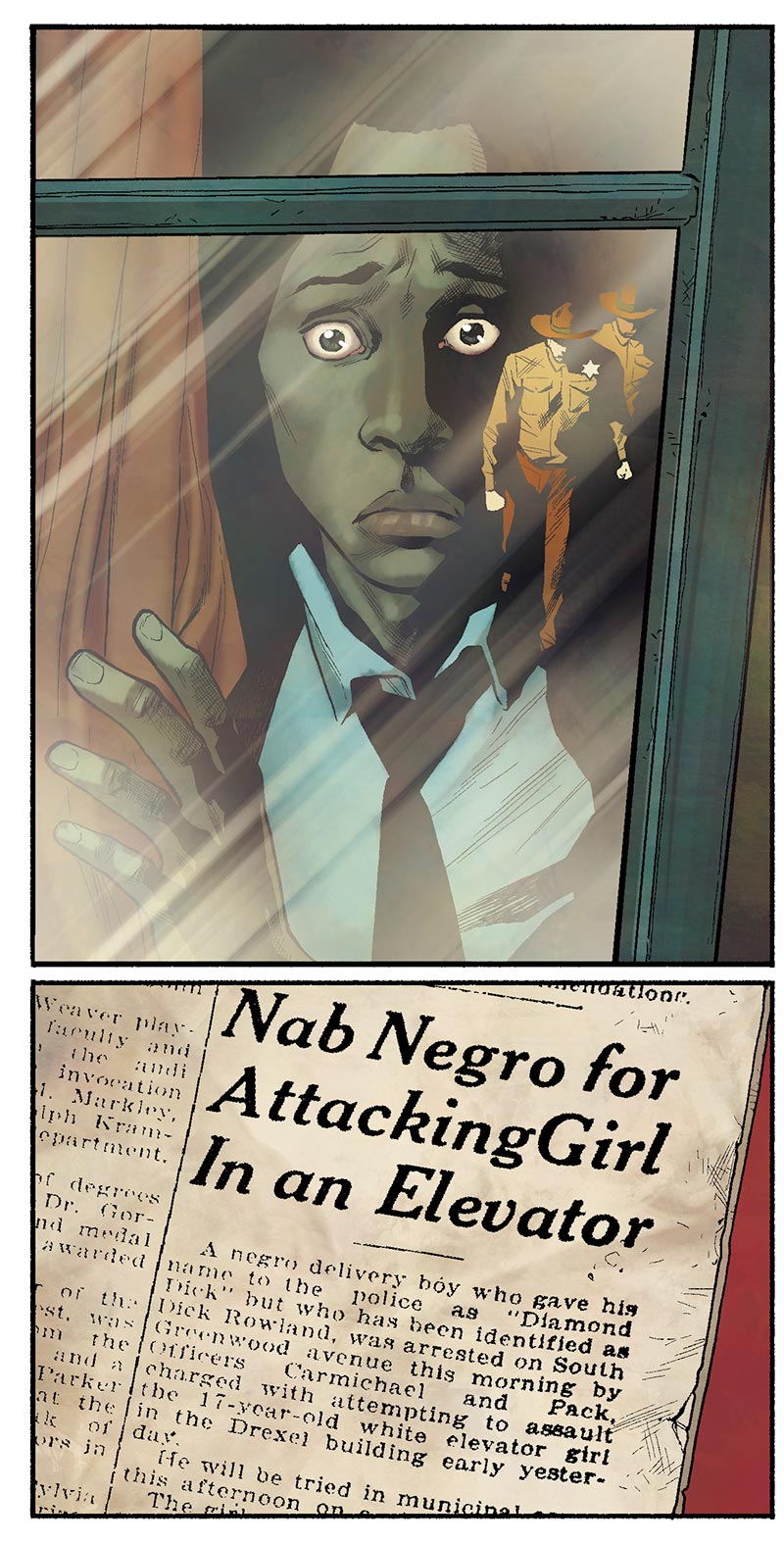

On the morning of May 30th, a few seconds in a building in downtown Tulsa brought all of those tensions to a head. Two teenagers — a black shoeshiner named Dick Rowland, and a White elevator operator named Sarah Page — crossed paths in an elevator.

Wow, what an intriguing image to share with us! Let’s delve into the details together. In this encounter on the elevator, we see two individuals adorned in striking, contrasting outfits. One figure is dressed in a pristine white outfit, exuding an aura of elegance and authority, while the other person is clad in darker attire that suggests a sense of mystery and solidity. The juxtaposition of light and dark creates a dynamic visual tension that immediately pulls us in.

What’s captivating here is the contrast not just in their clothing but in their expressions and stances. The person in white appears calm and composed, almost regal, while the person in dark attire has a more intense, focused demeanor, suggesting perhaps a tension or unspoken conflict between them. This visual dialogue between the two characters makes us curious about their relationship and the context of their meeting.

Another fascinating detail is the elevator setting itself. Elevators are often confined spaces that amplify the intensity of interactions. It’s almost like they’re in a pressure cooker where every gesture, every glance becomes magnified. This makes us wonder about the purpose of their encounter. Are they allies, adversaries, or strangers thrown together by circumstance?

One mystery that hovers around this image is the story that brought them to this moment. The background elements are minimal, directing all our attention on the two figures. It’s a snapshot filled with potential narratives. We can almost feel the weight of unspoken words and the anticipation of what might happen next.

Let’s reflect on this and consider how such scenes can speak volumes, even in silence. What do we feel drawn to in this image’s story? How do these visual elements guide our understanding of this encounter? We have so much rich material here to explore together!

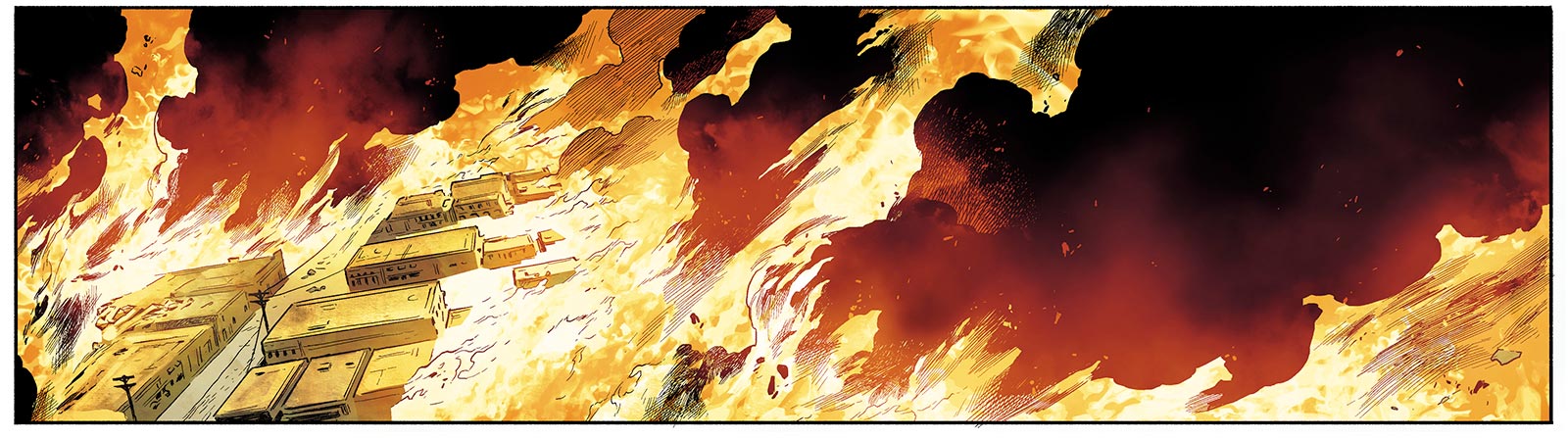

In the haunting image displayed, we bear witness to a powerful and poignant tableau from the violent and racially charged event that was the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921. The scene is painted with chaotic brushstrokes of human suffering and systemic brutality. Buildings, once symbols of hope and prosperity in the prosperous Greenwood District, popularly known as “Black Wall Street,” smolder and crumble under the onslaught of hatred-fueled arson. The sky is a surreal canvas of acrid smoke and fiery embers, casting an eerie, almost apocalyptic glow upon the landscape.

The central focus of the image is the collective anguish and pervasive fear etched onto the faces of Black residents—men, women, and children—whose lives have been violently torn asunder. These figures, desperate and forlorn, scramble for safety amid the pandemonium, their forms mere silhouettes against the incandescent backdrop of flames. It’s clear from their hurried movements and expressions of terror that they’re grappling with the immediate, visceral knowledge of their vulnerability in a society that has turned its back on protecting them.

In the periphery, shadowy figures, likely the perpetrators of this violence, add to the darkness of the tableau. They are indistinct, almost ghostly, as if the weight of their actions has rendered them less than human, specters of hate and destruction. These antagonists represent the brutal reality of the time—a period saturated with racial intolerance, institutionalized injustice, and a brazen disregard for Black lives.

The image captures not just a historical moment, but a stark emblem of the systemic racism that permeated the early 20th century. It reflects the harsh truth of a society where progress and prosperity for Black Americans were continually undermined by the specter of white supremacy. The Tulsa Race Massacre, which saw the decimation of a thriving Black community by white mobs, was a devastating manifestation of this dark chapter in American history. The deliberate destruction of homes, businesses, and lives serves as a chilling reminder of the lengths to which hate and bigotry were deployed to suppress Black advancement and enforce racial hierarchies.

In essence, this image is not merely a photograph but a visceral chronicle—a searing indictment of an era’s profound injustices and a solemn testament to the resilience of those who lived through one of America’s bloodiest racial pogroms. It’s a reminder that the consequences of unchecked racism and violence ripple through time, demanding from us not only remembrance but a commitment to confront and rectify the enduring legacies of such traumas.

Reporter’s Log: The Underbelly of the American Dream

Tulsa, Oklahoma, June 2, 1921**

As your humble scribe, tasked with unveiling the pestilent truths buried beneath the veneer of our so-called Roaring Twenties, I pen these words with a heart heavy and an inkpot brimming with sorrow and rage. Before my eyes lies not just a scene but a verse from the necromantic scriptures of purgatory—etched into our collective memory as the Tulsa Race Massacre.

Imagine, dear reader, a night where the moon refuses to shine its pale luminosity upon us, as if the heavens themselves are ashamed of the spectacle unfolding beneath their celestial gaze. Greenwood District, once a flourishing cradle of African-American enterprise, lies besieged by infernal forces of racial malevolence. The ghosts of this blackened paradise whisper tales of prosperity that once defied the chains of societal segregation. Alas, these whispers are drowned by the deafening symphony of crackling flames and thrumming chaos.

From my vantage point, I see the once-gleaming edifices of Black Wall Street, bastions of ambition and aspiration, now reduced to skeletal remains marred by soot and cinders. The air is a noxious miasma of smoke, asphyxiating and ominous, carrying with it the acrid scent of dreams thus cruelly incinerated.

The human figures dominate the centerpiece of this grim portrait. Their faces, contorted by mortal dread, are fettered in the raw ferocity of the moment. Men, stripped of dignity, clutch their kinfolk close, their eyes ablaze not with hope but with a desperate plea for survival. Women, the stalwart keepers of hearth and home, now resemble fleeting phantoms as they navigate a labyrinth of ruin in search of sanctuary. Children, their innocence shattered, cling to their mothers, their cries piercing the thick veil of smoke, each wail a mournful lamentation for a lost future.

Skulk in the shadows, the villains of this diabolical opera. Their forms are encased in silhouettes—dark specters brandishing torches and firearms, agents of havoc driven by a delirium of supremacy. In their barbarity, they evoke not just individual malevolence but the institutionalized odium that festers in the sinews of this nation. These figures are the grotesque avatars of an era that revels in—as the saying goes—boundless optimism and unbridled capitalism, yet unabashedly tolerates this malignancy of racial hatred.

The stark dichotomy between the victims and their aggressors is a painful reminder of the systemic injustices that infect the marrow of our society. The massacre’s orchestration—an unspeakable leviathan of collective white rage—merely underscores the fragility of Black success in a land that promises equality but delivers inequity with brutal efficiency.

And so, what does this vivid tableau portend for us, the inheritors of such tremendous legacies of pain and perseverance? This image is not a relic to be relegated to dusty archives, but a clarion call echoing through the annals of time. It demands remembrance of those ravaged by intolerance and a relentless pursuit of justice for the progeny of their resilience.

This, dear readers, is not merely history confined to the yellowing pages of tomorrow’s textbooks but a searing testament to the cyclical nature of our collective amnesia and the enduring struggle for a just, equitable America. It is an image etched not just in black and white, but in the vivid, scorching hues of heart-wrenching human suffering and unparalleled bravery.

What is seen in this image? How does the image reflect the truth or facts of the time?

ChatGPT

The image from the Atlantic article shows a depiction of the Tulsa Race Massacre, also known as the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921. This event took place in the Greenwood District of Tulsa, Oklahoma, which was a prosperous African American community known as “Black Wall Street.”

What is seen in the image:

Destruction and Fire: The image likely shows buildings on fire, smoke billowing into the sky, and possibly ruins or wreckage. This visual representation aligns with the historical fact that a large part of Greenwood was destroyed by fire.

Chaos and Panic: The scene may depict people running or in distress, capturing the chaos that ensued during the massacre.

Historical Context: Elements in the image, such as clothing styles or architecture, can provide context for the early 20th century, when the event occurred.

Reflection of Truth or Facts:

Destruction: The image reflects the actual destruction of over 35 city blocks, including homes, businesses, and churches, which were burned down during the massacre.

Violence: It represents the violent nature of the event, where a white mob attacked the African American community, resulting in the deaths of an estimated 100 to 300 people.

Economic Impact: The devastation of the thriving Black Wall Street, which was a symbol of African American economic success, highlights the racial tensions and the impact of white supremacy at the time.

Historical Suppression: For many years, the events of the Tulsa Race Massacre were omitted from history books and not widely acknowledged, reflecting a broader pattern of ignoring or downplaying racial violence in American history.

Overall, the image is a powerful visual representation of one of the most violent and devastating race riots in American history, capturing the horror and destruction faced by the Black community in Tulsa during that period.

The image from the provided URL shows a historical reenactment scene from the 2019 TV series “Watchmen.” This particular scene depicts the Tulsa Race Massacre, a tragic event that occurred in 1921 in the Greenwood District of Tulsa, Oklahoma, an affluent African American community also known as “Black Wall Street.”

In the image, we can see:

People running in panic, indicating chaos and violence.

Buildings on fire, reflecting the widespread arson that destroyed homes and businesses.

Smoke and debris in the air, enhancing the sense of destruction and terror.

Historical Context and Accuracy

The Tulsa Race Massacre began on May 31 and ended on June 1, 1921. It was one of the most severe incidents of racial violence in U.S. history. Here’s how the image reflects the historical facts:

Destruction of Greenwood: The image captures the destruction of a prosperous Black community. During the massacre, a white mob attacked Greenwood, looting and burning homes, businesses, schools, and churches. The fires in the image symbolize this devastation.

Violence and Panic: The chaos and fleeing individuals reflect the terror experienced by the residents. Many were killed, and thousands were left homeless. The depiction of people in distress accurately portrays the violence and fear.

Racial Tension: The massacre was a result of deep-seated racial tensions and jealousy towards the economic success of the Black community in Greenwood. The image, by showing the destruction and fear, indirectly highlights the racial animosity of the period.

The reenactment in “Watchmen” aims to bring awareness to a historically significant event that was largely ignored or downplayed in history books for many years. The series uses this historical context to explore themes of racial injustice, systemic racism, and the lasting impact of such events on American society.

That makes me think it was less of what she said and more of what that guy said. He most likely had something to do with it. Either way it also shows how even though those men were sexist and didn’t care to listen to woman they would if it helped them harm a black person. They have always divided minorities for their own benefit. Page could have change her story because police didn’t find it a very pressing matter.

May 31st. The day everything went up in flames.

As a female, I think another woman falsely accusing someone of something so horrific is so disgusting. It can ruin the lives of many people.

In my reading group today with Jasir, Tysherah, and Zyiar, we talked about how the media can sometimes increase racial tensions with their coverage.

Yeah, i agree maybe if the woman didn’t lie and the white people understood the situation more the black male wouldn’t get arrested I feel like they have no obligated reason to lynch him if he didn’t do anything to her but obvisouly they think he did it When propaganda began to spread the threatening words soon became actions.

Created By

Unidentified

Owned By

Ross, J. Kavin, American

Date

1921

Medium

silver and photographic gelatin on photographic paper, with ink on paper

Dimensions

H x W: 3 7/16 × 5 7/16 in. (8.7 × 13.8 cm)

Caption

On May 31 and June 1, 1921, in Tulsa, Oklahoma, mobs of white residents brutally attacked the African American community of Greenwood, colloquially known as “Black Wall Street,” in the deadliest racial massacre in U.S. history. Amidst the violence, both white rioters and the Oklahoma National Guard rounded up black residents of Greenwood and forced them to detention centers. More than 6,000 African Americans were interned at the Convention Hall, the Tulsa County Fairgrounds, and the baseball stadium McNulty Park. Some were held for as long as eight days.

Photo postcards of the Tulsa Race Massacre were widely distributed following the massacre in 1921. Like postcards depicting lynchings, these souvenir cards were powerful declarations of white racial power and control. Decades later, the cards served as evidence for community members working to recover the forgotten history of the riot and secure justice for its victims and their descendants.

Description

A sepia-toned photographic postcard of National Guardsmen with a machine gun mounted on the back of a flat-bed truck on the streets of Tulsa, Oklahoma during the Tulsa Race Massacre. Several soldiers are on the back of the truck with the weapon, one standing and one kneeling to the left of the gun and one at the gun sight. Several other soldiers march next to the truck, backs to the camera. Other vehicles and soldiers are visible on the street in the background of the image. Written in white at the bottom of the image is [NATIONAL GUARD / MACHINE GUN CREW / DURING TULSA RACE RIOT 6-1-21]. The verso is marked [POST CARD] at the top with spaces for [CORRESPONDENCE] and [ADDRESS] and an AZO stamp box in the top right corner.

Place Depicted

Tulsa, Tulsa County, Oklahoma, United States, North and Central America

Classification

Photographs and Still Images

Type

gelatin silver prints

photographic postcards

Topic

Communities

Military

Photography

Race relations

Race riots

Tulsa Race Massacre

U.S. History, 1919-1933

Violence

Credit Line

Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture

Object Number

2011.175.11

Restrictions & Rights

Public domain

Proper usage is the responsibility of the user.

GUID

http://n2t.net/ark

- Quoted Sentences:

1. “On May 31 and June 1, 1921, in Tulsa, Oklahoma, mobs of white residents brutally attacked the African American community of Greenwood, colloquially known as ‘Black Wall Street,’ in the deadliest racial massacre in U.S. history.”

– Importance: This sentence sets the context for the image by highlighting the significance of the historical event—the Tulsa Race Massacre. Understanding this event is crucial to comprehending why the image holds such historical weight.

2. “Photo postcards of the Tulsa Race Massacre were widely distributed following the massacre in 1921.”

– Importance: This sentence reveals how the event was commercialized and suggests a sinister motive behind the production and distribution of these postcards—to assert white racial dominance and possibly to intimidate African Americans.

3. “Like postcards depicting lynchings, these souvenir cards were powerful declarations of white racial power and control.”

– Importance: This draws a parallel with other historical atrocities, such as lynchings, where similar tactics were used to reinforce racial hierarchies and terrorize Black communities. Understanding this parallel helps to grasp the oppressive intentions behind the creation of such postcards.

4. “Decades later, the cards served as evidence for community members working to recover the forgotten history of the riot and secure justice for its victims and their descendants.”

– Importance: This sentence shifts the perspective from the initial use of the postcards as tools of terror to their later role as historical evidence in the struggle for justice. It highlights the importance of preserving such artifacts for historical accountability and education.

- Background Information:

To understand this text more deeply, several background topics need to be explored:

1. Tulsa Race Massacre: The event involved a large-scale attack on the prosperous Black neighborhood of Greenwood in Tulsa, Oklahoma, by mobs of white residents. Dozens, possibly hundreds, of African Americans were killed, their homes and businesses were destroyed, and thousands were left homeless. Knowing the details of this event helps contextualize the image and understand its historical impact.

2. Black Wall Street: This term refers to the Greenwood District, which was a highly successful and affluent African American community. Understanding its economic and cultural significance makes the violent destruction of Greenwood even more poignant.

3. History of Lynching Postcards: These postcards were used in a similar fashion—to glorify acts of racial violence and to intimidate and terrorize African Americans. Learning about these can show how such images were part of a broader pattern of racial terror in the United States.

4. Historical Preservation and Justice Movements: Understanding how historical artifacts are used in movements for justice and historical accountability can provide insight into why preserving such painful memories is essential for healing and education.

- Suggested Resources for Background Reading:

1. Books:

– “The Burning: Massacre, Destruction, and the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921” by Tim Madigan

– “Death in a Promised Land: The Tulsa Race Riot of 1921” by Scott Ellsworth

2. Articles:

– “The Tulsa Race Massacre: 100 Years Later” by The New York Times

– “What the Archives Reveal about Tulsa’s Infamous 1921 Race Riot” by History.com

3. Documentaries:

– “Tulsa Burning: The 1921 Race Massacre” (History Channel)

– “The Legacy of the Tulsa Massacre” (PBS’s “The African Americans: Many Rivers to Cross”)

- Re-engage and Reflect:

I invite you to revisit the text and the image, now armed with this deeper understanding of the historical context and significance. Perhaps there are additional details or questions that stand out upon re-reading. Feel free to share any new insights or thoughts that you have in a reply!

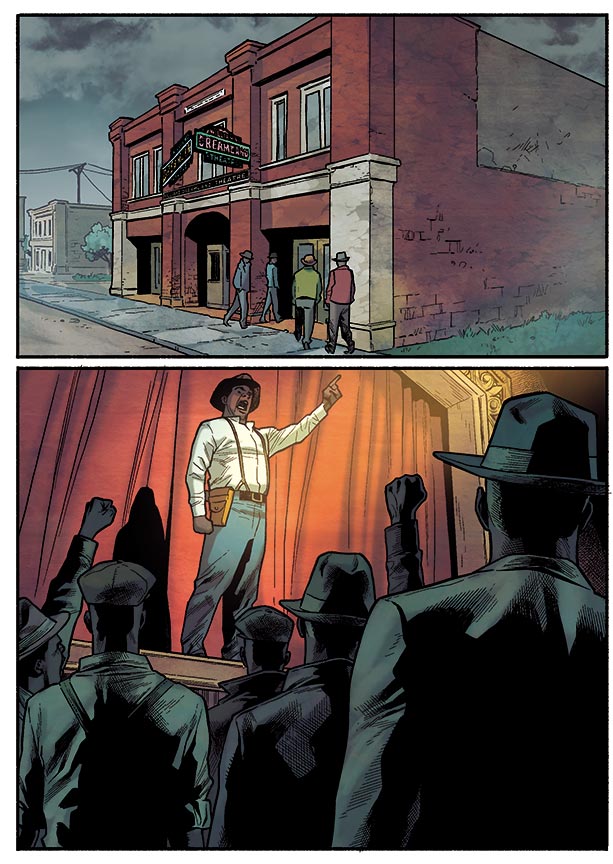

As they should! Even though they aint about that murdering others for the color of they skin life which is why the race war ended in them losing. The other side had the intention to kill, while they only had the intention to get be respected more. i think this whole situation could’ve been handled differently instead of going straight to violence

They were definitely ready for anything, it took a lot of power to go to the courthouse and stand up for their people despite the government not protecting them because of racism. So, the only people that can protect is your community. I honestly think they were tired and fed up and wanted something to change. So, they decided they were done seeing them get lynched and wanted to fight but they did not know that one of the most horrible events in history would happen. I honestly think the white mobs wanted to destroy their businesses and see them suffer and knew nothing would happen to them because of the racist system. I am also glad that came together as a whole group and fought against the white mobs. They were brave but also ready and prepared for anything that was going to try and stop them!

We also talked about how this black character in this comic panel reminded us of Uncle Ruckus Boondocks. We wondered why the illustrator chose to depict this character in this manner.

In our group, we noted that the character in the right with the mustache reminded us of the dictator Hitler of Germany. We wondered was it a coincidence that this character whom we assumed to be one of the white racists in the mob, resembled a noted historical figure who was responsible for killing lots of Jews.

they only killed these people off of what they saw and what they heard the chaos just started happening and they just started to kill anyone that was black that they’ve seen

This is interesting to me because it shows how mass incarceration has been going on for years and started back then and started to build up. So they locked up the black men and then they decided to do the riot? I wonder why they wanted to lock up some instead of leaving them there while they did that?

They haters! they did all this because a white woman lied about what a black man did to her and they had been waiting to do this. This is interesting because usually African-Americans are doing riots today and are held accountable but the white mobs burned down a whole community and weren’t held accountable, the community wasn’t even allowed to be rebuilt, the survivors weren’t paid, and they tried to keep it hidden from the world. I find this interesting because this shows how jealous they were to see a thriving successful black community. This also makes me connect this to economic conditions, how African-Americans got the economy stolen from them. How now today white people are put in the upper class and African-American people are put in the lower class. When really African-American community was in the upper class but it was stolen from them.

This is interesting because some people were saying that African-Americans just complain because they are not rich and that they don’t want to work to be successful but this shows that they did work hard and their hard work got stolen from them by the white mobs destroying their community. I genuinely feel like you can still be successful without being rich without a doubt! Wow! So even though African-Americans had their community burned down they were still going to rebuild it! This shows persistence and beyond courage! They could have easily given up and let the white people make them move somewhere else but they were willing to rebuild it!

I don’t think personally the night that the massacre had happened it should’ve been buried all those people that are the reasoning for this happened should’ve had every part of involvment in the massacre no matter what they decided to go to these peoples territory and just kill them over something they saw

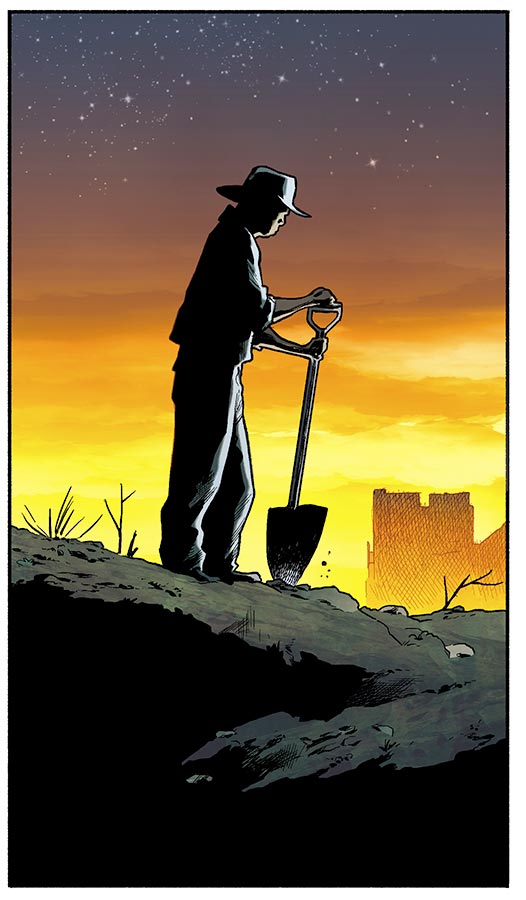

“If you bury something long enough, it can become very difficult to unearth.”

I find this very interesting because it makes us connect it to the world when an African-American is murdered by a white mob or police and it gets kept hidden and no justice is served then it be hard to bring justice later and it makes white people keep murdering and treating African-Americans terrible. That’s why it kept happening generations later since the start of slavery because they made it “normal”. By not doing anything the first time and just keeping it under the tuck and making it okay for other white people to do it.

Dr. Scott Ellsworth is a professor of Afroamerican and African Studies at the University of Michigan and author of Death in a Promised Land, the first comprehensive history of the Tulsa massacre. He was also one of the lead scholars for the Tulsa Race Riot Commission and a key player in the battle to secure reparations for survivors. According to him, the lasting trauma of the massacre is also intrinsically tied to the silencing of survivors.

This connects back to how African-Americans today fight for their rights by protesting and how African-Americans do whatever it takes to get justice for their people. This shows how we as black people keep fighting until justice is served! This also realtes back to THUG reading of when Starr stated while standing in front of the protesters and stated that they will proetsting until the police show they care about justice for black people.This shows how African-American people fight for the wrong that is happening to their people and how even an individual Dr.Scott Ellsworth can be powerful!

“For 50 years, the story was actively suppressed in Tulsa, and it was deliberately kept out of the White newspapers. The people who brought it up were threatened with their jobs; they were threatened with their lives,” he says. The story of the massacre indicts White America, which is why it was buried for so long. Without the perseverance and openness of the survivors of the riot, he says, there would be no mainstream acknowledgment of what happened in 1921.

Your telling me that the people of Tulsa put more energy into keeping the massive amounts of death out of the news paper but they but 0 effort into finding out what actually happened to that woman or find an actual way to fix the problem that’s just crazy and there always talking about change

This makes me think about what they tried to do to Emmett Tiil, they knew that what they did was horrible and that it would shock the world so they didn’t want the world to know what they did so they tried to cover it up by trying to bury his body in Mississippi like he never existed and here they are trying to hide what the white mobs did to Black Wall Street. I don’t get it,they do these terrible things and expect it to be kept a secret and hidden as if it never existed or matter. But in reality it is our history and it matters more than people think!

This is interesting to me because first they were trying to keep them from building and now they are trying to hide it… It’s like they are trying to make all their rights and freedom is gone.

why are they keeping what happened out the newspaper? i feel like this is so wrong because white people caused this riot and don’t want more people to know about it. or you could say they don’t want this story to get out.

This is intersting becasue it shows how white people are scared of African-Americans. They are not just scared of their skin color but also the voice and what we can do with our knowledge, this why this leads me back to slavery when they tried to stop African-Americans from learning how to read and write and this also takes me back to how some slaves started to learn. Did other slaves have connections and help them?

First I want to say that if there were no survivors nobody really would have even knew about Black Wall Street. I also had questions about how many survivors there were and how many out of the survivors told what happened. I saw the lady tell what happen but here it says survivor(s). I also wanted to know were the white mobs still alive when the survivors were and if so how did they react when they saw them speak out about it and were they ones that were trying to it keep hidden or was it the sheriff and government?

“Many Tulsans are just happy people are talking about [the massacre] at all,” adds Dr. Alicia Odewale, assistant professor of anthropology at the University of Tulsa. Odewale is currently working on a research project called Mapping Historical Trauma in Tulsa from 1921-2021 that reanalyzes historical evidence to visualize what happened to Greenwood during the massacre and in the years that followed it. “Ninety-eight years later, almost all of the massacre survivors have passed on, and it’s up to their descendants and the people left alive today to carry on their legacy.”

As of 2019, the city of Tulsa has yet to award reparations to the families of survivors and victims of the massacre. “The total estimated financial loss, taking into account the destruction of both private residential property and property in the business district would be about $50-100 million in today’s currency,” Odewale says. The neighborhood, in addition to being subjected to the on-the-ground assault, was bombed from above by planes carrying White assailants.

As an added insult, it took almost a full century for the search for the mass graves of victims to begin in earnest; they are currently ongoing. “If we discover the remains of victims, are able to identify them, and if those people are reburied with honors, that will be a huge moment for the city,” says Ellsworth. But it’ll be a moment for the country, too.

“White people remember history differently than African Americans do, and the reality is that we have one common history. There’s only one American history, and until we are able to confront the bad parts as well as the good parts, we’re never going to be on the same page on how we view the country, its promises, its problems,” Ellsworth says. “We still have a lot of work to do in Tulsa. There is no question. There is still a lot of hurt and anger over this.”

I find this interesting because maybe it’s because white people were given more opportunities and the experiences of African-Americans and white people are totally different, African-Americans have more terrible experiences, especially in history.

This makes me connect to how people try to story tell the brutal American history, the lies built upon America are what should be the history of it, not just what went well. There were good things that happened but what comes with the good things also has to come with the truth of the brutality that was done.

The hurt remains in part because of what happened after the fires burned out. In the days that followed the massacre, insurance companies refused to reimburse the damage done to Greenwood, since “riots” were not covered. As a result, in the weeks that followed the massacre, many of Tulsa’s Black residents were forced to languish in the makeshift holding areas they’d been taken to that night, or leave the city—and the community that they’d built—altogether.

“The accumulation of a massive amount of wealth and the loss of income that would have been earned, had Greenwood been allowed to thrive undisturbed, is almost incalculable,” says Odewale. “But just as important are the things that can’t be quantified, such as the loss of the sense of safety in their own city, the loss of trust in city officials, law enforcement, and in some cases, in people altogether.”

This isn’t to say that Greenwood was defeated. Over the next couple years, almost every destroyed home was rebuilt; in 1925, the National Negro Business League hosted its annual conference in the neighborhood, signaling the revival of Greenwood as a hub for Black business and entrepreneurship. The following decades brought commerce and culture back onto Greenwood Ave, and more recently, the city has made commercial investments into revitalizing the area.

But for many long-time Greenwood residents, revitalization is not reconciliation. In fact, revitalization can often be a codeword for gentrification that prices and pushes out community institutions, especially those owned by Black residents. At its worst, it might be a form of erasure. Some sources have theorized that the massacre was a calculated attempt by the city to seize the land, one that has taken on a new, contemporary form. “Modern-day gentrification and urban renewal projects, more commonly referred to in North Tulsa as ‘urban removal,’ continue to try to gobble up what is left of Greenwood,” Odewale says, adding that those “renewal” efforts aren’t targeted to who they should be. “The equality indicators released by the City of Tulsa every year continue to demonstrate that North Tulsans and South Tulsans are living completely different lives in what seems like two different cities…. Unfortunately, Black citizens in North Tulsa fall to the bottom of every metric.”

everyone is trying to leave the past in the past but it can’t be forgotten that easily.

Odewale criticizes contemporary redevelopment initiatives, arguing that they often displace long-standing residents and erode the cultural and historical fabric of historically Black neighborhoods like Greenwood, instead of benefiting the community members who need it most.

It took 80 years for the city to release an official report on the massacre, which recommended multiple forms of restitution, including financial reparations for survivors and their families. Calls for those reparations have been dismissed at multiple levels of the justice system, including the U.S. Supreme Court.

Wow, so it took them this many years just for it to be recognized in the world! Just because they see it is wrong now doesn’t mean this fixes anything that was done to Tulsa!

“I’m not sure any amount of money or social services, offered 98 years later, can make up for [the massacre],” Odewale says. “I’m in awe of how resilient the North Tulsa community continues to be, as efforts to rebuild and revitalize the Greenwood district have been ongoing since 1921. But at the very least, in my opinion, we need to have a serious plan for reparations, free housing and business support for descendant families, Greenwood business grants, college tuition scholarships for young students in North Tulsa…and a serious effort to close the median income gap between White and Black families in Tulsa.”

This makes me connect back to the economic condition of how white is put in the upper class and get paid more and African-Americans are put in the lower class and get paid less. This leads me back to opportunities that are given to them. But something defiantly needs to be done about repaying the Tulsans for what the white mobs did, they need to put more effort into it!

Odewale’s incisive perspective on the ways racial traumas of the past evolve and take form in the present is prescient for an entire country rife with incidents of White-on-Black violence, like the city-wide riots in Detroit in 1943, which mostly took its toll on Paradise Valley, a Black neighborhood. It helps illuminate truths about the relationships between segregation and law enforcement, land loss and land robbery, gentrification and history.

What should Greenwood and Tulsa look like today? We might start to answer that question by seeing what it looked like in the spring of 1921.

Required reading on the Tulsa massacre

- The Tulsa Race Riot and Three of Its Victims, by B.C. Franklin An unpublished manuscript written 10 years after the massacre by a witnessing survivor.

- Black Wall Street: The African American Haven That Burned and Then Rose From the Ashes, by Victor Luckerson A reported, researched look at the glory, razing, and rebuilding of Greenwood.

- Death in a Promised Land: The Tulsa Race Riot of 1921, by Scott Ellsworth The first comprehensive history of the events leading up to, during, and after the massacre.

- Tulsa Race Riot: A Report by the Oklahoma Commission to Study the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921 The published findings of an independent expert panel on the consequences of the massacre.

- ‘They Was Killing Black People,’ by DeNeen L. Brown A reported article about the lingering damages of the massacre, and how it affects Tulsa today.

Sources:

The Tulsa Race Riot and Three of Its Victims, by B.C. Franklin

Black Wall Street: The African American Haven That Burned and Then Rose From the Ashes, by Victor Luckerson

Death in a Promised Land: The Tulsa Race Riot of 1921, by Scott Ellsworth

Tulsa Race Riot: A Report by the Oklahoma Commission to Study the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921

‘They Was Killing Black People’ , by DeNeen L. Brown

University of Tulsa Archival Catalog: Tulsa Race Riot

Tulsa Historical Society & Museum

Tulsa, 1921: Reporting a Massacre, by Randy Krehbiel

Black Wall Street: From Riot to Renaissance in Tulsa’s Historic Greenwood District, by Hannibal Johnson

General Document Comments 0

It seems like Greenwood had a lot of positive things going on for herself. Where in Philadelphia can we find black-owned groceries stores, banks, hotels, theaters located within black communities? Did integration hurt or help black businesses https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k_hGNksmKDE

I think integration hurts black businesses because I think that black people are not supporting each other as much as they used to. I don’t see a lot of black businesses in black neighborhoods. Maybe segregation made it more for them to support each other and be a push for each other but now today that made has hurt them and they aren’t supporting each other as much. Maybe this event hurt them and now that may be why we don’t see as many black businesses in black communities.

he was running because if you see a black man and a white lady together they always thought the black man was going to harass or do something bad to her

0 archived comments